Earth Day 2016: Do people still care?

Loading...

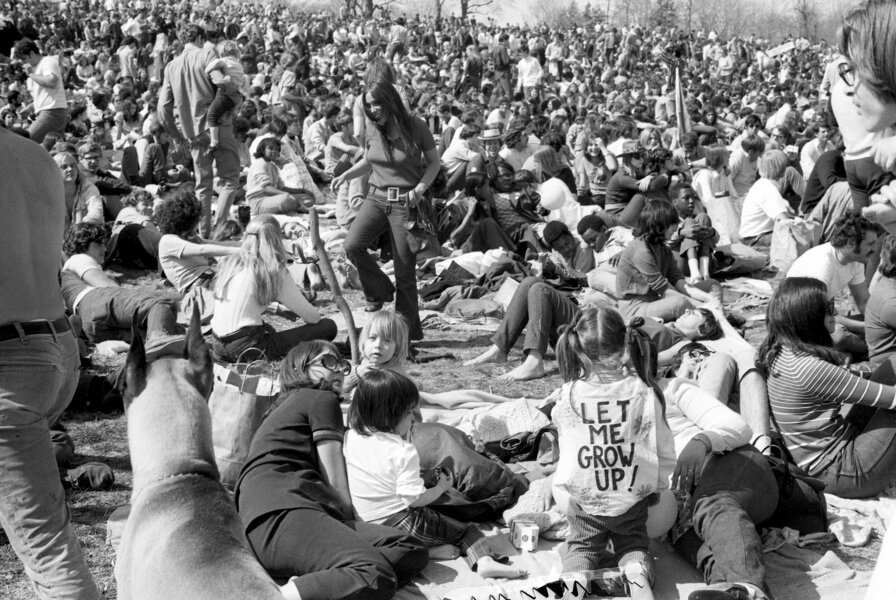

For the past 46 years, Americans have celebrated Earth Day on April 22.

"Earth Day is all things to all people," Frank Maisano, an energy-industry spokesman in Washington, told The Christian Science Monitor in 2008. "It's a symbolic representative of the desire for everything we need to do to respect how we treat the earth." April 22 is the officially designated Earth Day, but it's become more of an everyday mentality since its inception in 1970.

While public support for environmental protection has continued since the first Earth Day 46 years ago, little legislation has been passed at the federal level. Policy analysts and environmental historians say the drastic decrease in legislation between April 22, 1970 and April 22, 2016 can be attributed to congressional attitudes.

"A major thing has happened, and that's bipartisanship," Anthony Leiserowitz, director of Yale University's Project on Climate Change Communications, tells the Monitor in a phone interview.

"The environment – and more specifically climate change – is a highly contested political issue, which is very different from the 1970s," he says. "The politicians have gotten ever more divided [on environmental issues] but that's only because the parties themselves have become more divided. In the 1970s, people were co-sponsoring, voting across the aisle – but now it is all party line."

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed environmental legislation such as the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and more. But Earth Days in the 21st century don't have legislation to celebrate as frequently. The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, which encouraged energy efficiency, and the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act of 2009, which granted wilderness protection for 2 million acres of US land, account for the most recent nationwide legislation put into law.

Americans' views of environmental issues have "not changed drastically in recent years," according to a 2007 study from Pew Research Center. While the percentage of Americans wanting stricter environmental laws fell from 90 percent in 1992 to 82 percent in 1994, this rate has remained in the low 80s until today. And between 2009 and the first quarter of 2016, environmental issues have only increased in salience among Americans, suggests Gallup, with 64 percent of Americans worrying a "great deal" or a "fair amount" about global warming.

But although overall support for environmental protection remains stable, Pew notes, there has been a growing increase in partisan differences. In 1992, Democrats led Republicans in wanting stricter environmental laws, but only by 7 percent. This divide grew to 17 percentage points in 2003 and then up to 30 points by 2007. And in 2014, Pew found that a 43 percent gap between Republicans and Democrats who considered climate change a major threat to the US.

"There was a period of time at the turn of the 21st century [where public support dipped] but really for the last 50 years you see public opinion at 70 to 80 percent support," Steven Cohen, the executive director of Columbia University's Earth Institute in New York, tells the Monitor. "It's an issue that may have been controversial in the past but it hasn't been for a very long time – except for in the minds of about 30 people in the House of Representatives."

In fact, public support for environmental protection may even be stronger today than it was around the time of the first Earth Day, despite less legislative productivity.

"People have gone through school learning about these things, so the level of environmental awareness is much higher today than when I worked at the EPA in 1977," adds Dr. Cohen. "We barely understood environmental science. The average high school student knows more today than we did."

In those days, Earth Day was "in the spirit of 1960s and 1970s demonstration politics – it was symbolic politics," Cohen says. Today, he believes the holiday is better integrated with education and research, a reminder of "how important the planet is," and that the US needs to advance climate science in addition to environmental legislation.

Despite the legislative inaction that plagues recent Earth Days, the continued, broad public support for environmental protection is encouraging, some climate experts say.

"There are some things that are widely shared, [such as] the idea that the health of the environment is a good thing," adds Dr. Leiserowitz. "No one says it's OK to drive species extinct, for example, but that doesn't mean that these battles aren't incredibly intense."