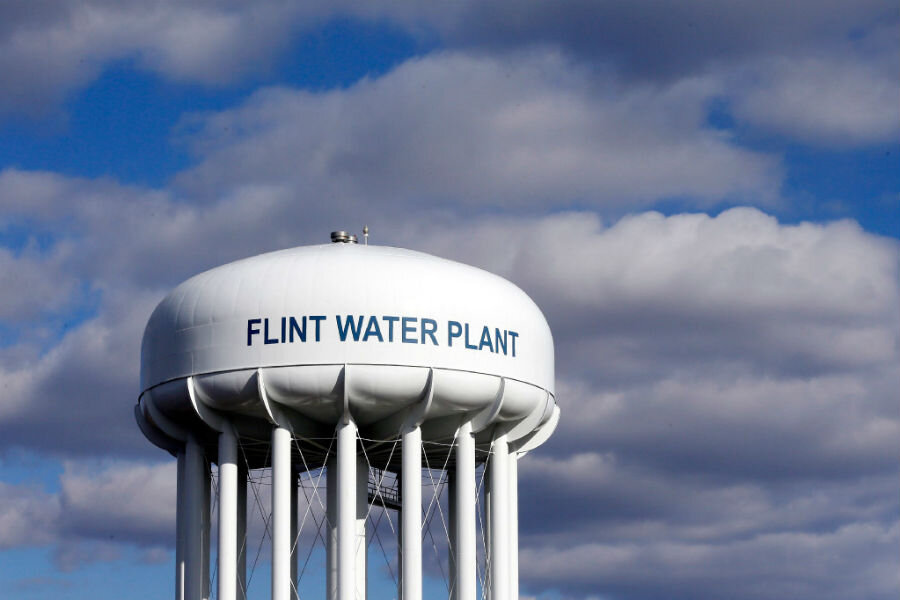

Is the end in sight for the Flint water crisis?

Loading...

Flint, Michigan's water crisis may finally be reaching resolution, with a new settlement that would require the city to replace 18,000 underground pipes by the year 2020.

The agreement, which was brought to federal court on Monday and is expected to be approved Tuesday afternoon, is part of the search for solutions to the high levels of lead and other contaminants that were measured in the city's drinking water in 2015. The settlement requires Michigan to provide at least $87 million, with an extra $10 million in reserve, to inspect and replace the pipes as well as provide the plaintiffs with $895,000 to recover legal fees. The agreement also funds deliveries of bottled water and filters to residents while the pipe replacement is underway.

The settlement is a major victory for the residents of Flint. The national outrage and outpouring of support for the city after its lead contamination was publicized two years ago has led to substantial changes for the community's water system, says Virginia Tech engineering professor Marc Edwards, who was one of the first people to identify the water contamination crisis in Flint.

But many of the problems that lead to the contamination still have to be addressed in other areas of Michigan and across the United States, he warns.

"Flint has actually been meeting all federal water safety standards for at least 6 months, and in similar situations, residents of other cities in the US are routinely told that their water is 'safe' to drink, even without filtration," Dr. Edwards tells The Christian Science Monitor via email.

"However, the State of Michigan and the US EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] have appropriately been erring on the side of caution in Flint, and continue to emphasize the use of water filters as a prudent additional safeguard against the lead in water," he adds.

"Flint still has serious problems associated with crushing debt and financial instability, which will keep water rates unaffordable for many Flint residents," Edwards writes. "This problem has not been solved."

About $30 million of the settlement will be paid out of $100 million in federal funds from an Obama-era law signed in December 2016. The state will be responsible for the rest of the $97 million.

"The proposed agreement is a significant step forward for the Flint community, covering a number of critical issues related to water safety," Dimple Chaudhary, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the groups behind the lawsuit, told the Associated Press. "It provides a comprehensive framework to address lead contamination in Flint's tap water."

The lead crisis in Flint began in April 2014, when a state-appointed emergency manager switched the city's water supply from Detroit water to the Flint River as a temporary cost-cutting measure.

Flint's water treatment plant had not been required to use corrosion-control chemicals in the treatment process, and as a result, river water began to corrode the pipes, leaching lead into the city's drinking water. Many officials initially denied that there was a problem, and the mayor even drank a glass of tap water on TV to prove that it was safe. Following the public outcry, Flint switched back to the Detroit water source in October 2015.

But much of the damage had already been done, says Eric Feigl-Ding, an epidemiologist at Harvard Chan School of Public Health.

"The Flint crisis is more than just water lacking corrosion control, but also the corroded lead pipes," he tells the Monitor via email. "Replacing all the lead service lines (the pipes from street to each individual home) will take a long time."

Dr. Feigl-Ding, who is also the founder of Toxin Alert, a non-profit network and public alert system for toxic drinking water contamination, notes that many Flint residents have already suffered health problems from lead poisoning. He says negligent officials involved in the crisis still need to be brought to justice.

The new settlement requires the state to replace 6,000 water lines by Jan. 1, 2018, and at least 6,000 more lines in each of the two following years. The agreement also guarantees services like on-demand bottled water delivery within 24 hours, increased availability of water-filter consultants to residents, Medicaid expansions through March 2021, and independent monitoring of the water lines after their re-installment by the state.

Virginia Tech's Edwards says that the settlement represents an important step forward for Flint – and for communities across the country struggling with similar water problems.

"The higher standard of protection being offered for Flint residents is likely to be employed in some form for residents of other Michigan and U.S. cities in the near future," he says.

"This new 'Flint Standard' should be considered for many other cities with old infrastructure, who currently have even worse lead in water problems than Flint."