G8 leaders tackle inequities of global oil, coal extraction

Loading...

G8 leaders took on corruption and exploitation in global resource markets at this week's G8 summit.

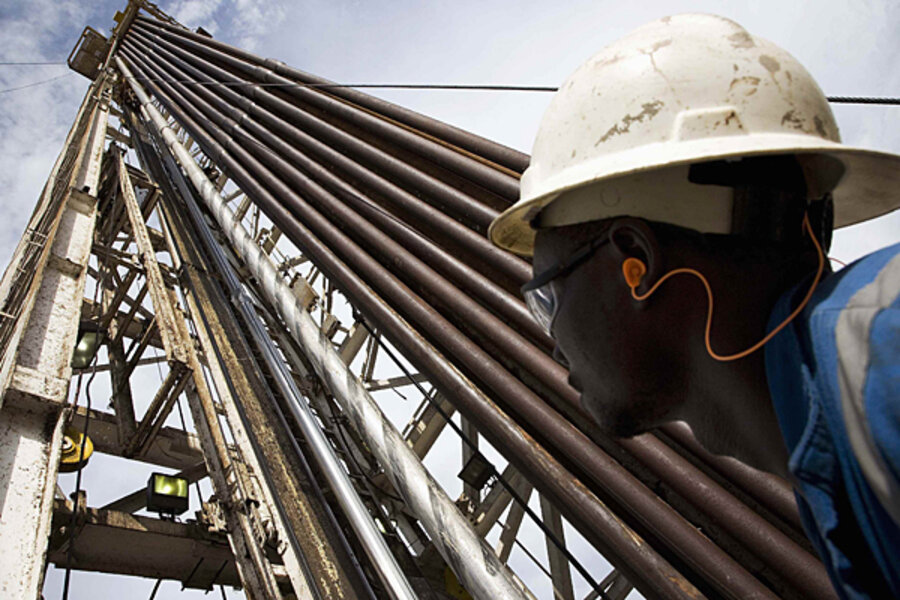

Many of the world's most valuable resources happen to fall in the poorest places on the planet. Large, multinational companies mine precious oil, gas, and coal from developing African, Asian, and Middle Eastern nations.

That can generate much-needed job growth and infrastructure development, but the exchange isn't always balanced. Host countries are often stripped of commodities for profits to be made halfway around the world. In other cases, corrupt leaders exchange their national resources for their own personal profit.

"Mineral wealth for developing countries should be a blessing, not a curse," British Prime Minister David Cameron said in a statement last month. "And I urge our G8 partners to champion the same high standards of transparency."

As host of this year's G8 summit, Mr. Cameron has made extractives transparency part of the agenda. It may not be the broad-reaching discussion of global energy issues and climate change that loomed large over previous summits. But the focus on equitable resource extraction shines a light on a consequential, if relatively obscure, issue.

In the lead up to the summit, the United Kingdom announced it will join the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), an international standard that promotes revenue transparency and accountability in global oil and gas extraction.

The initiative requires companies to publish what they pay governments for mineral resources and for governments to disclose what they receive from the extractives industries. Making that information public means governments and private industry can be held more accountable for what exactly changes hands over the global mineral marketplace.

Twenty-three countries have become EITI-compliant since its formation in 2002. The coalition is made up mostly of African nations, which together have disclosed more than $1 trillion in mineral revenue. France joined the UK in announcing its plans to join EITI last month, and 16 other countries are candidates for compliancy.

The US is not yet a candidate country, but President Obama announced an intention to comply with EITI in 2011. The Department of Interior hosted a public meeting on the subject earlier this year.

“Big strides have been made in the global movement towards transparency in the management of the extractive industry," Jonas Moberg, head of the EITI International Secretariat, said in a statement Monday. “We still have to do more to make sure that the right questions are asked to ensure better management and more benefits for the citizens.”

Half of the global population – 3.5 billion people – live in countries rich in oil, gas, and mineral resources, according to the G8. Exports of those commodities out of Africa totaled more than $338 billion in 2010. That's seven times the mount of money that came into Africa from foreign aid.