The conservative Christian college where Muslims feel welcome

Loading...

| Salt Lake City

Brigham Young University is hardly a place you’d expect Muslim students from halfway around the world to spend some of their most formative years, perhaps. But freshman Hind Alsboul is embracing life here as one of 44 Muslim students on a campus of more than 33,000, where roughly 98 percent are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Like Islam, the church has at times been one of the most popularly reviled religions in America. But the student experience here offers a unique window on what acceptance and understanding look like between two frequently misunderstood faiths. Church history “makes us really aware of … people who are seen as marginally American by others, as maybe not fitting in, as being ‘the other,’ ” says James Toronto, a BYU associate professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies. Church members know about “that struggle to find our place in the broader polity and society, and so I think there’s a lot of empathy for other minority groups who are going through that same struggle.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onBeing a tiny minority in a community can amplify differences. But at BYU, a common history of being the "other" leads to a learning atmosphere of empathy.

The average July temperature in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia is about 97 degrees.

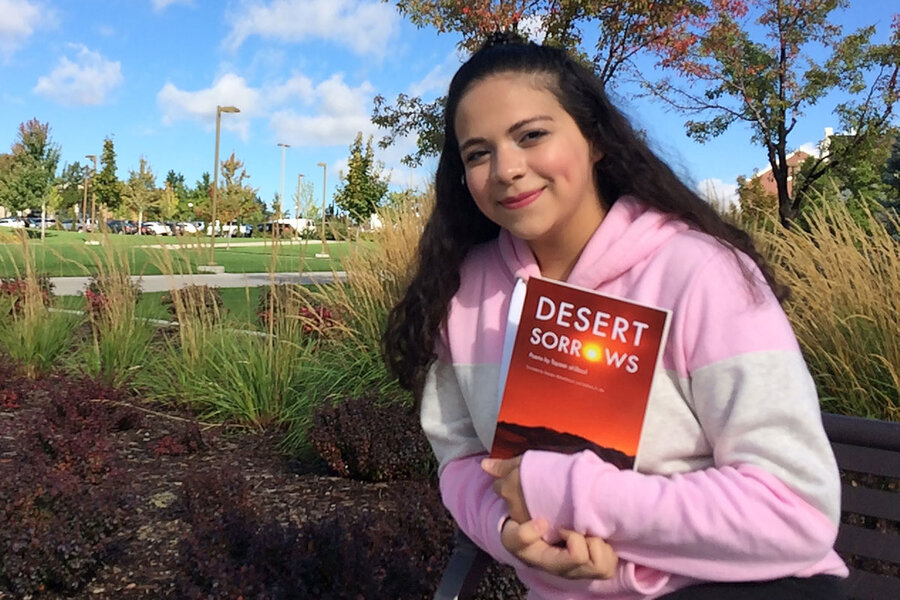

But for five of those July days, Hind Alsboul slowly circled along the roof of her family’s home, wobbling in unsteady lines atop her brand-new bike. In two weeks, she and her parents would fly to Salt Lake City, where she would begin life as a freshman at nearby Brigham Young University. And a particular orientation course had caught her and her father’s eyes. It involved canoeing, biking, hiking – in short, many things that Ms. Alsboul had never done since her family moved to the Kingdom from Jordan, nine years before.

Never mind that she couldn’t ride a bike. Never mind that their neighborhood didn’t have bike lanes, or that when riders did venture out under the sun, they were almost never women. Never mind that, when Alsboul finally did brave the streets, with her father riding behind in support, people were yelling and whistling and taking pictures – and she wasn’t sure it was encouragement.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onBeing a tiny minority in a community can amplify differences. But at BYU, a common history of being the "other" leads to a learning atmosphere of empathy.

“He was like, it doesn’t matter,” she says. “You’re doing this because you’re changing into a better person.”

Today, dashing back from statistics class in a pink and white sweatshirt, Alsboul is embracing life at BYU – and is an enthusiastic survivor of her orientation. She likes the popular Sunday night singing sessions in campus tunnels (her favorite hymn is “Come, Come Ye Saints”), and the department she wants to major in, communications disorders.

Alsboul is also one of 44 Muslim students on a campus of more than 33,000: a campus where roughly 98 percent of students are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Sometimes, those students say, it can feel isolating. But their experiences also offer a unique window on what ideas like acceptance, and understanding, look like day to day, playing out between two frequently misunderstood faiths.

Like Islam, the LDS Church has at times been one of the most popularly reviled religions in America – with early criticisms of founder Joseph Smith, in fact, comparing him to Muhammad, and not as a compliment. Today, that legacy has informed a quiet but firm defense of religious freedom, particularly for Muslims in the United States. Historians of the church, not all of them members, filed two amicus briefs in opposition of the Trump administration’s recent “travel ban.”

BYU is hardly a place you’d expect a non-LDS student from halfway around the world to spend some of their most formative years, perhaps. It is a hub of LDS thought and faith – and “a kind of finishing school for Mormons,” jokes Islamic studies and Arabic professor Daniel Peterson. But BYU is also a place of openness. Here at the base of the Wasatch Mountains, a string of peaks and blazing, nubble-covered slopes, nearly half of students have lived abroad, and two-thirds speak a second language – thanks, in part, to the lengthy missionary trips so many serve. An all-encompassing Honor Code, prohibiting alcohol, drugs, premarital sex, and immodest dress both on campus and off, can be just as welcome for Muslim students – and their parents – as for Mormons. And then there’s Utah: as of April, the only state in the nation where Republican officials have not publicly attacked Islam since 2015.

Church history “makes us really aware of … people who are seen as marginally American by others, as maybe not fitting in, as being ‘the other,’ ” says James Toronto, a BYU associate professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies, who has been involved in LDS academic and humanitarian engagement in the Middle East for decades. Church members know about “that struggle to find our place in the broader polity and society, and so I think there’s a lot of empathy for other minority groups who are going through that same struggle.”

Most of the Muslim students are international, including a significant percentage who identify as Palestinian or Jordanian. From a distance, Utah might well seem like the America some had pictured, a bit nervously, before their arrival. Ninety-six percent of BYU Cougars are from the United States; 82 percent are white. More than 1 in 3 hail from conservative Utah – the center of LDS influence since the church’s second president, Brigham Young himself, led early adherents West in the 1840s.

For Nada Almassry, a sophomore from Egypt, BYU’s initial draw was the strength of its business program, and the cost. (Tuition for non-church members this year is $11,240; church members pay half that.) After spending her first year in the US at the University of Oklahoma, she appreciates BYU’s Honor Code atmosphere for making her lifestyle a point of connection, not distance.

“This actually helps [me]” meet people, she says, gently tugging on her headscarf and grinning, “because I’m easily stopped. ... Some people are curious, some people want to learn Arabic, some people are just like ‘As-salām 'alaykum’ [Peace be upon you], and that’s it!”

“Many people think Muslims have their religion as the center of their life,” says Hussam Eddin Qutob, a recent graduate now living in East Jerusalem, where he grew up. That’s true insofar as “we consider Islam a way of life, as a pivotal pillar.... We live by it, but it’s not the center of attention. We don’t wake up thinking of religion, go to sleep thinking of religion.” To Mr. Qutob, it’s the ties of culture, more than faith, that define the Arab community on campus.

At home in Ramallah, “It was rude to ask someone what their religion is,” says Dalia Abu Al Haj, a senior from Palestine who is majoring in public health. Here, that’s hardly the case, she says – and sometimes welcomes it. But she draws a distinction in how it’s asked: “What is your religion?” sounds like an attempt to categorize someone, she says; “What do you believe in?” – a deeper attempt to understand. The world’s 1.8 billion Muslims, she says, “are not one big committee, all the same.”

Prayers in class

At BYU, faith infuses more than social life. Among the hardest classes on campus, for LDS and non-LDS students alike, are the religion requirements, including several classes specifically about the church’s history and doctrine.

And religion courses aren’t the only place faith shows up in class, with LDS history occasionally making its way into material from accounting to science, and the use of prayers to sometimes kick off class.

“It can get pretty difficult from both sides,” academically and emotionally, says Laith Habahbeh, a junior from Jordan who, in his role in the Student Advisory Council, tries to look out for non-LDS students’ needs.

Sometimes people “gift you the Book of Mormon or something, that’s not a coincidence. They would like you to read it,” Qutob says. “But it’s in a smooth way. You don’t want to read it, they don’t follow up … it’s their way of sharing their gift, and we have to respect that,” he says.

In the 1990s, as part of an effort to send a message of respect to the Muslim world – and solve the problem of trying to teach Islamic philosophy without translations – Professor Peterson and the school created the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative, up until recently hosted by BYU. The texts are a series of affordable, dual-language editions, with English and Arabic running side by side – of use not just to scholars and students, but Muslims who do not know Arabic. “So there’s no cheating, it’s the original text,” Peterson says. “It’s not us talking about them, it’s us helping them to speak.”

Many Americans’ image of the church involves neatly-dressed, name-tagged pairs of missionaries proselytizing. But many aspects of LDS doctrine encourage openness toward other faiths, such as belief in continuing revelation.

“We’re open to the idea that there’s truth out there, and part of our job is to gather it up, wherever it is, and it doesn’t matter where it comes from,” says Peterson. “Could there have been inspiration outside the Mormon community, or outside Christendom? Yes, absolutely. We’re not only not surprised, we expect it.… It’s faith-affirming, if anything else.”

Sharing of cultures

Back in the sprawling student center, Alsboul rests outside the bowling alley, as mid-morning foot traffic picks up and someone picks out hymn variations on a nearby piano. She’s dived into learning about LDS, including the Sunday services, as a sign of respect for the community around her.

But she’d like to share her culture, too – maybe with Arabic lessons, she says, or with some of her favorite Jordanian poems, composed by her own grandfather. “I just want people to know more about who we truly are,” she says. “I just want to show that we’re better than what they hear.”

One of Qutob’s proudest moments at BYU came from choreographing a Palestinian dance, the dabka, for a student troupe. Seeing the word “Palestine” on the program, listed among the many countries whose cultures were represented at the event, was powerful, he says.

Islam is so often stereotyped, he says, but he notices that the LDS Church is as well.

“It’s like, I feel for you people,” he adds. “I would love to live in a world where – let’s call ourselves underdogs – underdogs support one another.”