IBM's Watson: Can a computer outsmart a Jeopardy! braniac?

Loading...

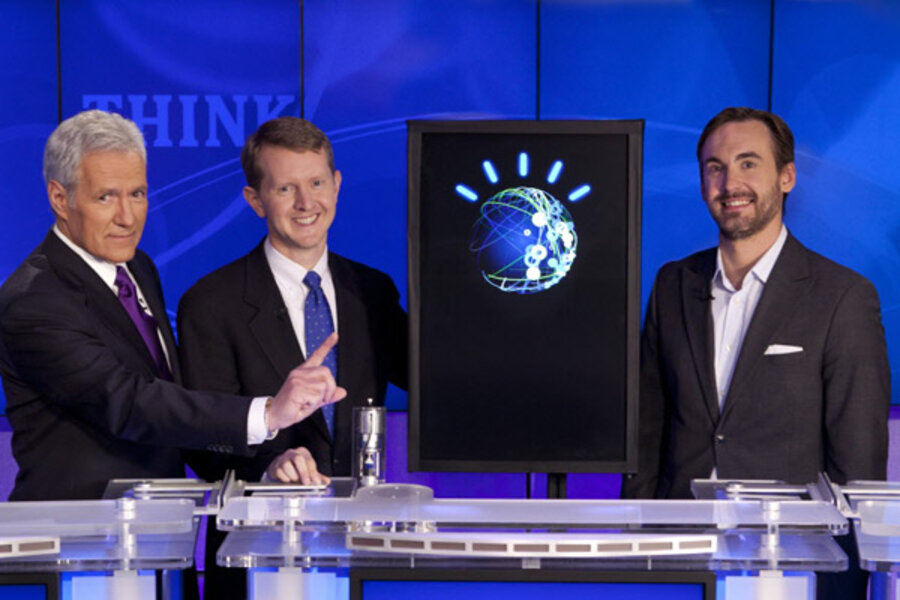

For three nights next week, an IBM computer called Watson will compete on "Jeopardy!" against the popular quiz show's two most successful human champions. The nationally televised event is the highest-profile match between man and machine since 1997, when IBM's Deep Blue defeated chess world champion Garry Kasparov.

Regardless of whether it wins or loses, Watson will continue to grab headlines. But does Watson represent a real advance for artificial intelligence (AI)? And could the computer actually lead to applications someday — other than schooling us at one of our own games?

To find out, TechNewsDaily spoke with several AI researchers not directly involved with the IBM project. All agreed that based on what they've already seen and heard about Watson – at least as it heads into its big test – the machine is quite an achievement.

"This is not a stunt," said Ted Senator, vice president and technical fellow at the Science Applications International Corporation, the current secretary-treasurer at the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, and a former "Jeopardy!" champ himself.

Perhaps the most obvious reason why, according to Senator: The 25-member strong team IBM pulled together four years ago for the Watson project could easily have failed. "It's not something where they picked a problem you know you can solve – 'Jeopardy!' was invented completely independent of AI as a game show."

Watson's skin, guts and 'brain'

Viewers won't have any trouble figuring out which player is Watson – above a "Jeopardy!" contestant podium, the "face" of Watson will loom as an atomic nucleus-looking sort of avatar that changes colors based on how confident the computer is in its answers.

But that's window dressing: Watson – all 3,000 computer cores of it – exists backstage as a cluster of black cabinets about the size of 10 refrigerators.

Just like its flesh-and-blood competitors Ken Jennings, who has the longest winning streak on the show at 74, and Brad Rutter, the all-time "Jeopardy!" money-earner with winnings totaling more than $3.2 million, Watson is entirely self-contained. Like a human, the machine is not connected to the Internet; whatever it knows is contained in the physical space of its "brain."

Watson's programmers have fed it on the order of 200 million pages of text, including encyclopedias, thesauri, novels, plays, past "Jeopardy!" clues and answers and other information-rich sources. Hundreds of algorithms then allow the machine to sift through these reams of text.

Unlike a search engine, which merely points to a Web page or document that might have the sought-after information, Watson must boil things down to discrete answers. The machine then probabilistically ranks its answers and if a threshold of confidence is crossed, it buzzes in on "Jeopardy!"

Understanding natural language

Perhaps surprisingly, Watson’s greatest difficulty won’t be coming up with answers — but figuring out what is being asked in the first place.

IBM refers to Watson's operations as "deep question answering," and parsing "Jeopardy!" clues is no easy task. The clues are written in "natural language" – the way people actually speak, with sly allusions, subtle humor and hidden meanings, rather than semantically unambiguous command prompts.

"By far, the biggest contribution of Watson has been to deal with natural language," said IBM's David Gondek, a researcher on the Watson project.

"Our language evolved assuming our level of intelligence, and it gets very hard for a machine to understand," said Michael Dyer, a professor of computer science at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

"You can say, 'John picked up a bat and hit Bill, there was blood everywhere.' We know it's Bill's blood and that it's a baseball bat, not a flying mammal," Dyer said.

That sort of linguistic abstruseness has long stymied computers, and posed the chief hurdle for the IBM team in breaking down "Jeopardy!" clues into relevant components. Another major challenge: coming up with an answer in the three seconds or less available after "Jeopardy!" host Alex Trebek stops reading the clue.

"I thought we'd be able to [get answers] accurately, but I didn’t know we'd be able to do it so quickly," said Gondek.

A limited form of intelligence

Watson, it should be made clear, does not understand the topics it hurls answers out about in the same way that a human can.

"[Watson] doesn’t need deep knowledge, but broad knowledge," said Rich Korf, also a professor of computer science at UCLA. "It cannot sit down and explain how an internal combustion engine works – it simply retrieves associations with clues. But that's not a trivial thing to do."

Indeed, scientists who have gotten a sneak peak at Watson's ability to decipher the types of "Jeopardy!" clues it will encounter in the showdown – even ones predicated on a bodily experience of actual space via prepositions, say – have walked away impressed. (IBM has closely guarded Watson's vulnerabilities so as to avoid influencing the show's clue writers.)

"Categories I predicted it would do terrible in it did well, and that’s what opened my eyes," said Jim Hendler, a professor of computer and cognitive science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who has seen some of the sparring matches IBM has run.

After final 'Jeopardy!'

Of course, the true value of Watson will not ultimately be its ability, however impressive, to win at quiz shows. IBM talks of applications in health care, call center support and other sectors that rely on real-life answer-seeking – just the sort of thing at which Watson excels.

Researchers spoke of Watson helping doctors consider diagnoses for patients. Watson could plow through the latest (as well as the oldest) medical literature for obscure — yet relevant — case studies given a list of symptoms, accessing far more information than a physician could ever keep in his or her head.

Fielding questions in the natural language people actually use might well be easier than cracking open a riddle-filled "Jeopardy!" clue. If we call an insurance agency asking about what medical insurance policy to buy, for example, we're not trying to trick the person handling the call, Senator said.

Show time

The three "Jeopardy!" episodes featuring Watson will air Feb. 14 through Feb. 16. The contestants have good reason to fear Watson: The computer won a practice round on Jan. 13 with $4,400 to Jennings' $3,400 and Rutter's $1,200.

UCLA's Korf is excited about what success for Watson could mean for the AI field, and as such, "I'll probably be rooting for the machine," Korf said.

Hendler sees the soon-to-air "Jeopardy!" contest as the present-day philosophical equivalent of the Deep Blue showdown, wherein an ability once thought to be uniquely human – the capacity to play masterful chess – now becomes machine territory.

"We have to go back and think about knowledge and data and questions and answers and society in a different way because no longer can we just say a stupid human can do this and a smart computer can't," Hendler said. "Now the question becomes, 'what are real differences?'"

"I think if AI science will take this as seriously as we should," Hendler added, "it'll rock us to our core."

• 10 Revolutionary Computers

• 5 Reasons to Fear Robots

• 10 Profound Innovations Ahead