What is subtropical plankton doing in Arctic waters?

Loading...

Samples of plankton collected in the Arctic Ocean near Norway revealed something surprising: single-celled creatures that belonged thousands of miles to the south where the conditions are balmier.

This may sound like a story about the surprising effects of global warming, but it isn't. At least not entirely.

That's because the researchers believe these warm-water invaders, called Radiolaria, are likely the result of an isolated pulse of water that carried them beyond the usual extent of the northbound Gulf Stream, a current that travels from the Gulf of Mexico into the northern Atlantic Ocean.

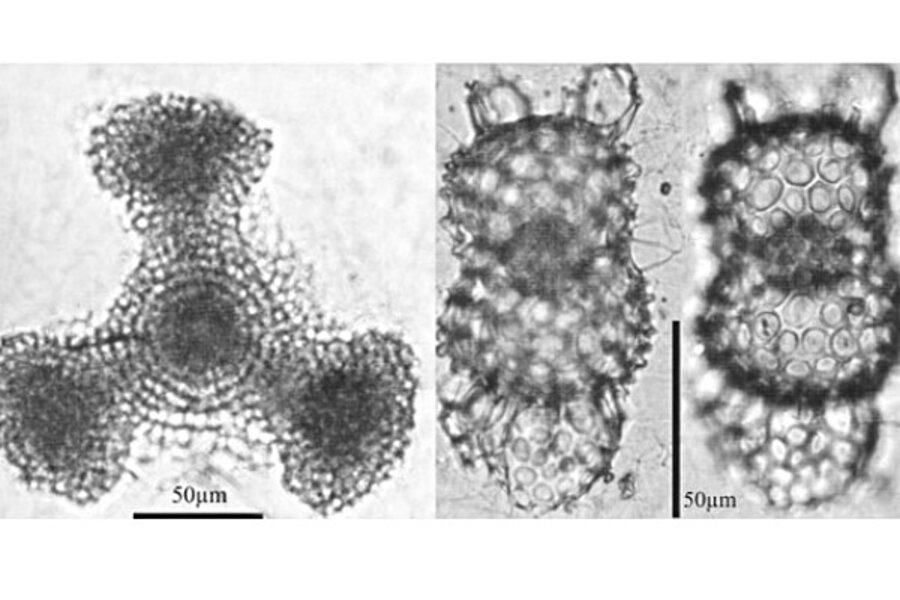

Radiolaria have ornate, glassy shells, and they eat algae and other microscopic organisms. Different species live in different temperature ranges. [Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

In 2010, a ship operated by the Norwegian Polar Institute collected plankton samples northwest of the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean. Of the 145 types of organisms in these samples, 98 came from farther south, as far as the tropics.

The discovery of living organisms like these in the northern waters was unprecedented, but the quirk in ocean circulation that scientists believe carried them this far north is not. Pulses of warm water have reached along the Norwegian coast and into the Arctic basin several times in the 20th century. What's more fossil evidence suggests warm-water plankton may have become temporarily established in the Arctic multiple times during past millennia.

"This doesn't happen continuously — but it happens," lead researcher Kjell Bjørklund, of the University of Oslo Natural History Museum, said in a statement.

While researchers don't think this particular incursion is the direct result of global warming, ocean scientists generally expect changes in ocean circulation to bring more southern water, and the organisms it contains, farther north.

For instance, warming is expected to weaken a current, the North Atlantic Polar Gyre, that prevents the Gulf Stream from penetrating farther north. Changing wind patterns and the influx of freshwater from melting sea ice and glaciers could also result in more southern water being drawn north, said Arnold Gordon, head of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory's division of ocean and climate physics at Columbia University, in a statement. Gordon was not involved in this research.

"When we suddenly find tropical plankton in the Arctic, the issue of global warming comes right up," study researcher O. Roger Anderson, a specialist in one-celled organisms at Lamont-Doherty, said in a statement. So, it's important to critically examine evidence that may explain observations like this one, Anderson said.

A description of the radiolaria discovery appears in the July issue of the journal Micropaleontology.

Follow Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

- Image Gallery: Rich Life Under the Sea

- Top 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming

- The World's Biggest Oceans and Seas

Copyright 2012 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.