Did scientists find a lost continent beneath the Indian Ocean?

Loading...

The remains of a micro-continent scientist call Mauritia might be preserved under huge amounts of ancient lava beneath the Indian Ocean, a new analysis of island sands in the area suggests.

These findings hint that such micro-continents may have occurred more frequently than previously thought, the scientists who conducted the study, detailed online Feb. 24 in the journal Nature Geoscience, say.

Researchers analyzed sands from the isle of Mauritius in the western Indian Ocean. Mauritius is part of a volcanic chain that, strangely, exists far from the edges of its tectonic plate. In contrast, most volcanoes are found at the borders of the tectonic plates that make up the surface of the Earth.

Investigators suggest that volcanic chains in the middle of tectonic plates, such as the Hawaiian Islands, are caused by giant pillars of hot molten rock known as mantle plumes. These rise up from near the Earth's core, penetrating overlying material like a blowtorch. [What Is Earth Made Of?]

Mantle plumes can apparently trigger continental breakups, softening the tectonic plates from below until they fragment — this is how the lost continent of Eastern Gondwana ended about 170 million years ago, prior research suggests. A plume currently sits near Mauritius and other islands, and the researchers wanted to see if they could find ancient fragments of continents from just such a breakup there.

Digging in the sand

The beach sands of Mauritius are the eroded remnants of volcanic rocks created by eruptions 9 million years ago. Collecting them"was actually quite pleasant," said researcher Ebbe Hartz, a geologistat the University of Oslo in Norway. He described walking out from a tropical beach, "maybe with a Coke and an icebox, and you dig down underwater into sand dunes at low tide."

Within these sands, investigators discovered about 20 ancient zircon grains (a type of mineral) between 660 million and 1,970 million years old. To learn more about the source of this ancient zircon, the scientists investigated satellite maps of Earth's gravity field. The strength of the field depends on Earth's mass, and since the planet's mass is not spread evenly, its gravity field is stronger in some places on the planet's surface and weaker in others.

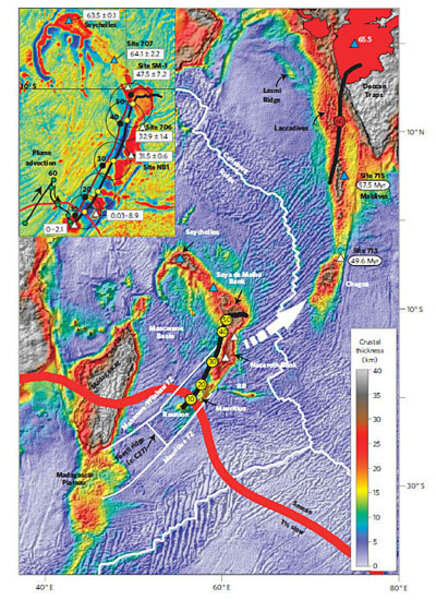

The researchers discovered Mauritius is part of a contiguous block of abnormally thick crust that extends in an arc northward to the Seychelles islands. The finding suggests Mauritius and the adjacent region overlie an ancient micro-continent they call Mauritia. The ancient zircons they unearthed are shards of lost Mauritia.

The researchers meticulously sought to rule out any chance these ancient grains were contaminants from elsewhere.

"Zircons are heavy minerals, and the uranium and lead elements used to date the ages of these zircons are extraordinarily heavy, so these grains do not easily fly around — they did not blow into Mauritius from a sandstorm in Africa," Hartz told OurAmazingPlanet.

"We also chose a beach where there was no construction whatsoever — that these grains did not come from cement somewhere else," Hartz added. "We were also careful that all the equipment we used to collect the minerals was new, that this was the first time it was used, that there was no previous rock sticking to it from elsewhere."

Peeling continent pieces

After analyzing marine fracture zones and ocean magnetic anomalies, the investigators suggest Mauritia separated from Madagascar, fragmented and dispersed as the Indian Ocean basin grew between 61 million and 83.5 million years ago. Since then, volcanic activity has buried Mauritia under lava, and may have done the same to other continental fragments.

"There are all these little slivers of continent that may peel off continents when the hotspot of a mantle plume passes under them," Hartz said. "Why that happens is still mind-boggling. Why, after something gets ripped apart, would it rip apart again?"

Finding past evidence of lost continents normally involves tediously crushing and sorting volcanic rocks, Hartz explained. The researchers essentially let nature do the work of pulverization for them by looking at sand.

"We suggest lots of scientists try this technique on their favorite volcanoes," Hartz said.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also onFacebook & Google+.

- World's Weirdest Geological Formations

- Earth Quiz: Mysteries of the Blue Marble

- 50 Interesting Facts About The Earth

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.