How astronomy solved a Civil War mystery

Loading...

Thanks to astronomy, the 19th century mystery surrounding the death of Confederate general "Stonewall" Jackson during the Civil War may finally be solved.

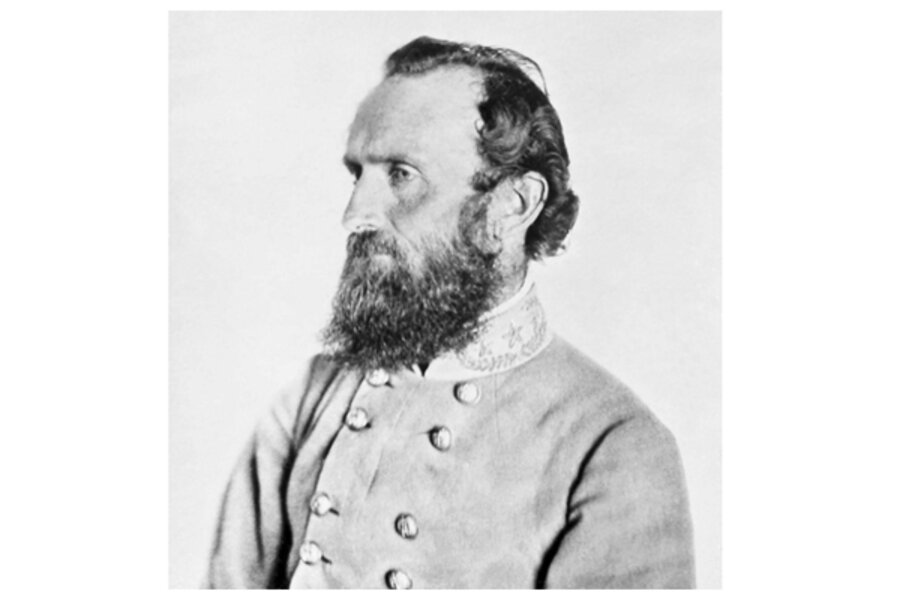

Lieutenant General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson was a major figure in the Civil War, second in command to Confederate general Robert E. Lee, when he was shot by friendly fire during the Battle of Chancellorsvilleon May 2, 1863. Shortly after that battle in northeastern Virginia, Jackson died of his wounds, leaving the Confederate army without one of its boldest military strategists just two months before the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg.

But exactly how Jackson's own troops could have mistaken him for the enemy has been unexplained until now. [Astronomy Detectives Solve Civil War Mystery (Photos)]

Famous "flank attack"

Firsthand accounts of the Chancellorsville battle describe how Jackson kept his troops fighting into the night — a rarity at the time. That same day he had accomplished a major victory, squashing the Union's Twelfth Corps in a famous "flank attack." When the sun set that night and the sky darkened, Jackson pressed on, continuing the fighting by moonlight. It was then that a Confederate officer on the left wing of the 18th North Carolina regiment spotted Jackson and a group of riders coming toward him.

Mistaking his commander for advancing enemies, Major John Barry ordered his troops to fire. Jackson was hit with bullets in his right wrist and left arm, which had to be amputated, and died of complications from pneumonia eight days later.

Hi death has been described as a blow of bad luck, and Barry reportedly "felt extreme guilt over giving the command to fire," according to historian James Gillispie's book "Cape Fear Confederates" (McFarland, 2012).

But now, astronomers say they know why Barry couldn't identify his commander — it's all because of the moon. Astronomer Don Olson of Texas State University and Laurie E. Jasinski, a researcher and editor at the Texas State Historical Association, report their findings in the May 2013 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine.

Space sleuths

"I remembered reading long ago that Stonewall Jackson was wounded by 'friendly fire' and that it happened at night," Olson told SPACE.com in an email. Olson decided to pursue the mystery on the occasion of the battle's 150th anniversary.

Olson and Jasinski calculated the moon's position and the lunar phase using astronomical software, and figured out exactly where Jackson's party, as well as the 18th North Carolina regiment, would have been at the time of the shooting, around 9 p.m. that night. They used Confederate almanacs in Richmond at the Virginia Historical Society, as well as battle maps by Robert Krick, a military historian who is an expert on the Battle of Chancellorsville, Stonewall Jackson and the Civil War in Virginia.

"Once we calculated the compass direction of the moon and compared that to the detailed battle maps published by Robert Krick, it quickly became obvious how Stonewall Jackson would have been seen as a dark silhouette, from the point of view of the 18th North Carolina regiment," Olson said.

Historical mysteries

Olson has used astronomy to solve other historical whodunits before. For example, he calculated the direction of moonlight on the night of Paul Revere's ride in 1775 to explain why Revere wasn't spotted by British sentries on a nearby ship, and exposed how moonlight allowed soldiers on the Japanese I-58 submarine to see, and sink, the USS Indianapolis in 1945.

"We are always interested in any historical event that happened at night — very often, the moon plays an important role, as happened here," Olson said.

This latest discovery may help restore the reputation of Barry and the 18th North Carolina regiment, which "unfortunately became famous and best known for accidentally wounding Stonewall Jackson,"Gillispie wrote.

Jackson's death was mourned not just by his troops and fellow generals, but by the civilian public in the South. He is still regarded as one of the greatest military tacticians in U.S. history, and he earned his famous nickname for leading his troops to stand against attackers like a stone wall.

Without a trick of the moonlight on that fateful night, Jackson may not have died, and historians debate whether the outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg, or even the whole Civil War, would have been different.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

- Busted: 6 Civil War Myths

- Album: Faces and Injuries of the Civil War

- How to Observe the Moon (Infographic)

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.