After big bang, galaxies wasted no time forming, Hubble data show

Loading...

Galaxies appear to have matured much sooner in the early universe than previously estimated, adding intriguing twists to the history that astronomers are compiling of the growth and evolution of these vast collections of stars.

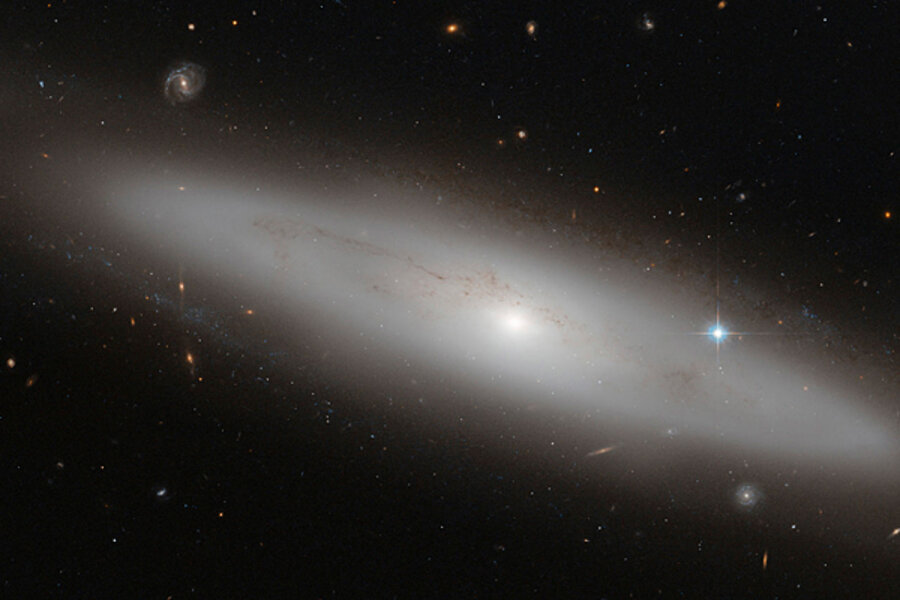

Using data gathered by the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of scientists found that galaxies of all sizes had fallen into two main shapes – disks and spherical – by 2.5 billion years after the big bang (an enormous release of energy that cosmologists say gave rise to the universe humans observe today).

The analysis by BoMee Lee at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and her colleagues clearly shows that these galactic geezers not only were common some 11 billion years ago, but also had emerged as a distinct group within a couple of billion years after the earliest known galaxies formed, says Mauro Giavalisco, an astronomy professor at UMass Amherst and Ms. Lee's PhD adviser.

The challenge to understanding galaxy evolution: Spherical galaxies essentially are "red and dead." Their stars are almost as old the universe. And some process has quenched their star formation – a process that could involve supermassive black holes at their galactic centers or the cumulative effect of intense star formation prior to becoming spherical galaxies.

The new analysis "provides compelling evidence that quenching is fast and incredibly effective in spheroids," Dr. Giavalisco says. Now researchers have to figure out why.

The results stem from the Hubble Space Telescope's CANDELS project, short for the Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey. It's the largest observing program in the storied observatory's history. Its main objective is to track the evolution of galaxies from less than 1 billion years after the big bang through today.

The survey uses cameras on Hubble that capture visible light and near-infrared light. Looking in the infrared is particularly important because these galaxies appear at distances of more than 11 billion light-years away. Because the universe expands with increasing speed with distance, light from a galaxy that would appear as visible light or as ultraviolet light – an indicator of star formation – if the galaxy were nearby gets stretched into the infrared region of the spectrum. Spherical galaxies, which tend to be red to begin with, can be fiendishly difficult to detect at such distances because their light gets driven even deeper in the infrared portion of the spectrum.

The three-year project began in 2010 and has in essence stared at the sky for the equivalent of four months.

Star formation requires the presence of cold, dense gas, which under favorable conditions can collapse to form stars. If the gas gets too hot, star formation stops.

Researchers have offered up two possible ways to generate such heat: One is the enormous radiation from supermassive black holes in galactic cores; the other is the formation of large numbers of very massive stars in a relatively confined regions.

These processes can heat gas to temperatures ranging from millions to 1 billion degrees. Once gas reaches those temperatures, cooling it essentially takes the lifetime of the universe.

"This is why it's really important to understand when these galaxies formed and when galaxies started to diversify into spirals and spheroids," Giavalisco says.

Other researchers had uncovered evidence that the galaxy types began to diversify as early as 8 billion years ago, but the studies also focused on low-mass galaxies, rather than the full range of sizes.

This latest work represents "a robust statistical assessment" showing that this divergence, known as the Hubble sequence, was happening much earlier than previous studies had indicated, Giavalisco says.

Whatever theorists devise to explain the quenching, it will have to include a process that happens very quickly, he concludes.

The results have just been published online by the Astrophysical Journal.