Why were early galaxies so dusty? Exploding stars may hold clues.

Loading...

| Washington

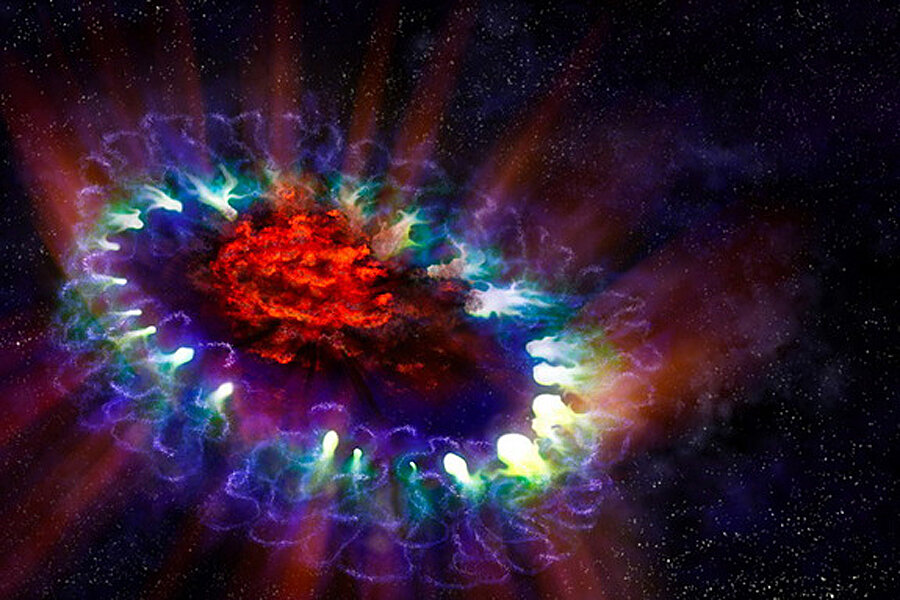

New views from a giant radio telescope in Chile are revealing massive amounts of dust created by an exploding star for the first time.

Scientists used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) radio telescope in Chile to make the discovery while observing supernova 1987A, an exploded star in the Large Magellanic Cloud — a dwarf galaxy companion of the Milky Way located about 168,000 light-years from Earth.

Astronomers have long thought that supernovas are responsible for creating some of the large amounts of dust found in galaxies around the universe, yet they haven't directly observed the process until now, ALMA officials said. [See more amazing images from the ALMA telescope]

"We have found a remarkably large dust mass concentrated in the central part of the ejecta from a relatively young and nearby supernova," astronomer Remy Indebetouw, of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) and the University of Virginia, said in a statement. “This is the first time we've been able to really image where the dust has formed, which is important in understanding the evolution of galaxies."

If enough of the dust created by 1987A and other supernovas like it transitions into interstellar space, it could explain part of why many galaxies in the early universe got their copious amounts of dust, Indebetouw said.

"If at least one third of it makes it out, then we're in good shape," Indebetouw said here at the 223 meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

"1987A is a special place since it hasn't mixed with the surrounding environment, so what we see there was made there," Indebetouw said in a statement. "The new ALMA results, which are the first of their kind, reveal a supernova remnant chock full of material that simply did not exist a few decades ago."

Astronomers have observed small amounts of hot dust in 1987A before, however, the research didn't reveal the large amounts of cold dust seen by ALMA radio telescope recently. The telescope's sensitive instrumentation was able to pick up on the cold dust in millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths, ALMA officials said.

1987A now holds about 25 percent of the mass of the sun in new dust, ALMA officials said.

"Really early galaxies are incredibly dusty and this dust plays a major role in the evolution of galaxies,"

Mikako Matsuura, a scientist associated with the study of the University College London, said in a statement. "Today we know dust can be created in several ways, but in the early universe most of it must have come from supernovas. We finally have direct evidence to support that theory."

ALMA is jointly operated by the European Southern Observatory, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

- 10 Biggest Telescopes on Earth: How They Measure Up

- ALMA Telescope Array - Revolutionizing Our View of the Cosmos | Video

- Meet ALMA: Amazing Photos from Giant Radio Telescope

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.