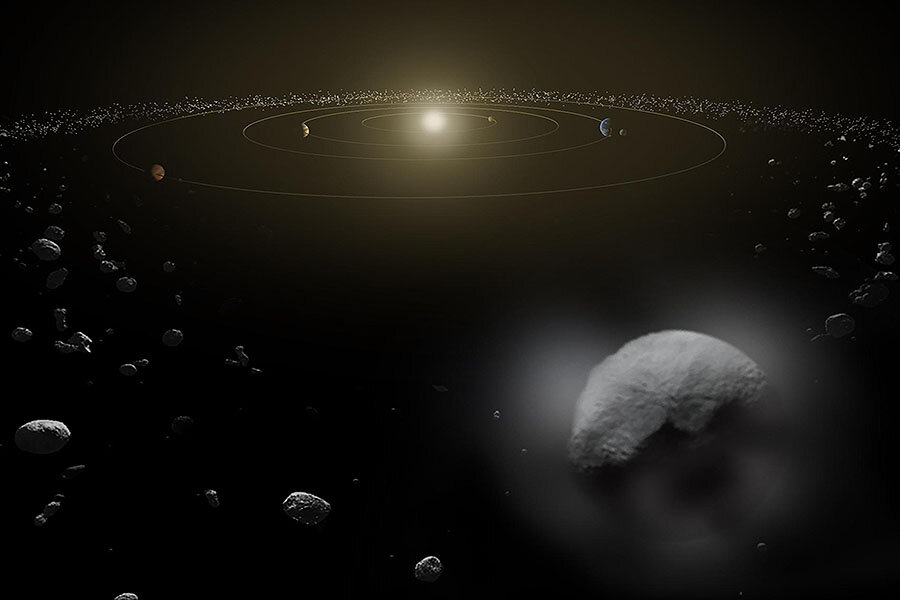

Water vapor on mysterious dwarf planet intrigues scientists

Loading...

The fictional depiction of asteroids as dull, grey lumps of rock has taken a beating lately.

Scientists using the Herschel space observatory have detected jets of water vapor on Ceres, the most massive resident of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

This "clear, spectral signature" of water vapor shoots up periodically in plumes at a rate of about 13 pounds per second, according to a press release by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif.

A paper on the research findings titled "Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres" appears in the current issue of the science journal Nature.

"This is the first time water vapor has been unequivocally detected on Ceres or any other object in the asteroid belt and provides proof that Ceres has an icy surface and an atmosphere," said Michael Küppers of the European Space Agency, and the lead author of the paper.

The Herschel telescope has an instrument that can determine the radiation coming from a celestial object and generate a high-resolution spectrum image, Seungwon Lee of JPL, who helped with the water vapor models told the Monitor. And this spectrum clearly showed the presence of water vapor in Ceres, she adds.

Herschel took four snapshots of Ceres at different points in the dwarf planet's orbit, it detected water vapor in three of those instances.

The reason, says Dr. Lee, could be Ceres' slightly elliptical orbit. When it is close to the sun, the icy surface becomes warm and releases water vapor, and when it veers away from the sun, no water is seen, she adds.

The findings will be an important bonus for Dawn, a NASA spacecraft due to reach Ceres in March or April next year, Marc Rayman, mission director and chief engineer of Dawn, told the Monitor.

After spending more than a year orbiting Vesta, the second most massive object in the asteroid belt, Dawn, the robotic emissary, will now focus on Ceres, Rayman says.

"Dawn will map the geology and chemistry of the surface in high resolution, revealing the processes that drive the outgassing activity," said Carol Raymond, the deputy principal investigator for Dawn at JPL.

Analyzing the largest two bodies within the asteroid belt can teach us about the origins of our solar system, Rayman says. Vesta and Ceres are particularly important because they were already in the process of growing into full-fledged planets. These bodies may retain a record of the time planets were formed, he says.

Ceres was earlier known as the largest asteroid in our solar system. But in 2006, the International Astronomical Union, the governing organization responsible for naming planetary objects, reclassified Ceres as a dwarf planet because of its large size – roughly 590 miles in diameter, according to the press release.

Ceres is now classified as a dwarf planet – a body in the solar system that is bigger than an asteroid but smaller than a planet.