So what is a supermassive black hole anyway?

Loading...

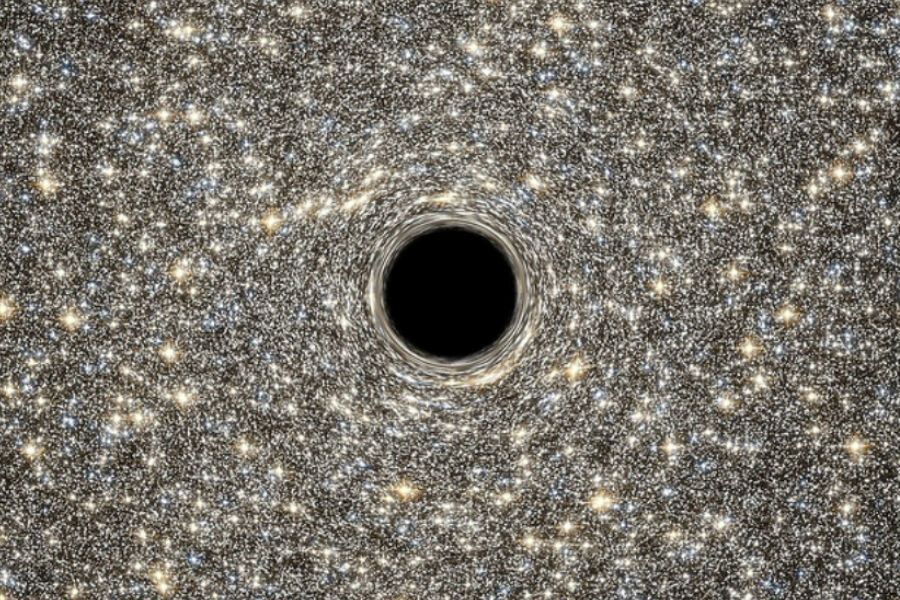

The discovery of a supermassive black hole inside a tiny dwarf galaxy has shed new light on the potential number of black holes in the universe.

An international team of researchers has discovered a supermassive black hole in M60-UCD1, a dwarf galaxy some 54-million light years away. M60-UCD1 is about 500 times smaller than our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and 1,000 times less massive. The researchers published their findings Wednesday in Nature.

Scientists have previously identified numerous supermassive black holes throughout the universe – including one at the center of the Milky Way. But this is the first time that any of these largest types of black holes have been found in such a small galaxy, says study lead author Anil Seth, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The revelation that a supermassive black hole can exist within an ultracompact dwarf galaxy could mean that there might be twice as many of these largest black holes than astronomers previously thought.

Black holes come in several different varieties, all of which are characterized by a dense concentration of mass compressed into a tiny space and a gravitational force so powerful it keeps light from escaping.

The smallest kind, called a primordial black hole, is the size of a single atom, but it contains the mass of a large mountain. The most widely understood black holes are known as stellar black holes and can contain 20 times the mass of the sun within a ball of space with a diameter of about 10 miles. Supermassive black holes can be as vast as the entire solar system and contain as much mass as found in 1 million suns combined.

Primordial black holes are believed to have formed during the early evolution of the universe, shortly after the Big Bang. Stellar black holes are thought to be the result of the collapse of a massive star. The formation of supermassive black holes has so far remained something of a mystery.

“We know supermassive black holes exist in the center of most big galaxies … but we actually don’t know how they’re formed,” says Dr. Seth. “We just know they formed a long time ago.”

Black holes are difficult to study because their tendency to pull light inside their centers renders them effectively invisible. Telescopes can observe contextual clues that suggest the presence of a black hole, such as stars orbiting around an apparent void.

“We can actually see stars moving around the center of the supermassive black hole of our galaxy,” Seth says. “It is much more difficult to study smaller galaxies.”

This particular dwarf galaxy happens to have so many stars – and a black hole that is so large – that telltale signs of the black hole were detected by two telescopes, the optical/infrared Gemini North telescope atop Hawaii’s Mauna Kea and the Hubble Space Telescope.

Typically, the size of a black hole is directly proportional to the size of the galaxy. Seth suspects that M60-UCD1 is actually the remains of a much larger galaxy.

“We think that this thing is a galaxy where the outer part of the galaxy has been stripped away by an interaction with another bigger galaxy and that the core has been left behind,” Seth explains.

In general, however, current technology has not yet reached a point that enables astronomers to definitively identify the presence of black holes in smaller galaxies.

By studying this and other black holes, scientists hope to unravel some of the mysteries of the origins of the universe.

“It turns out that black holes actually play a pretty big role in how galaxies form,” Seth says. “To understand our origin story we need to understand the formation of galaxies. And black holes, even though they are just a tiny fraction of all the mass in the galaxy, can play a really important role in their evolution."