Animals that baffled Darwin finally placed on family tree

Loading...

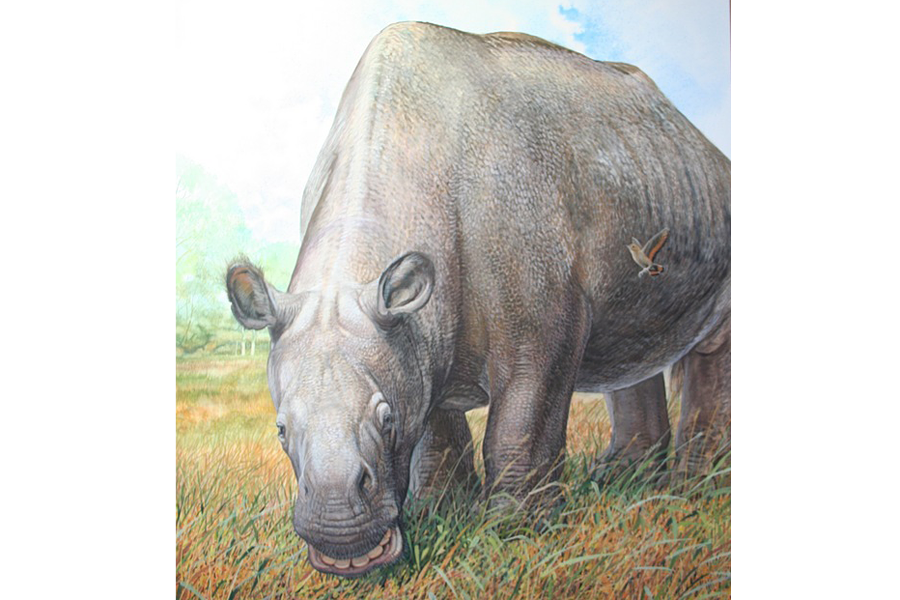

The origins of two wacky beasts that Darwin dubbed the "strangest animals ever discovered" had remained a mystery for some 180 years. But now, researchers say they've pinned down the evolutionary history of the two odd creatures — an ancient horselike animal with a long snout, and a rhinoceros-shaped animal with a head like that of a hippopotamus.

The new study reveals that these ungulates (hooved animals) native to South America descended from an ancient group of mammals called the condylarths — a sister group to the perissodactyls, which includes horses, tapirs and rhinos.

Charles Darwin first collected the two species, in the genuses Macrauchenia and Toxodon, during his South American voyage on a ship called the Beagle. He purchased fossils of the rhinolike Toxodon from a rancher in Uruguay for a few shillings, and collected fossils of Macrauchenia, which sported a muzzle that looked like an anteater's snout, in a sandy channel on the coast of southern Patagonia, said study co-author Duncan Porter, a professor emeritus of biological sciences at Virginia Tech. [What the Heck?! Images of Evolution's Extreme Oddities]

Famed for first postulating evolution, Darwin "soon recognized that these gigantic mammals might provide clues to his understanding of species formation," Porter told Live Science. "As he looked at other living mammals, he felt that they were related to those, but they were much smaller. And he wondered how that could have happened."

Darwin speculated that Toxodon's rhinolike body might mean it was related to the rhinoceros. Or, maybe its head, which resembled a hippo's, indicated that Toxodon was a hippopotamus relative, he surmised. Or, Darwin guessed, it might be related to an armadillo. On the other hand, Macrauchenia, with its long neck, might be related to a guanaco, llama or a camel (sans the hump).

But over the years, scientists have debated the exact families of these species.

"The problem is not a lack of fossils — there are thousands of South American-native ungulate fossils in museums in many countries — nor is it a lack of ideas and possible explanations," said Ross MacPhee, a curator in the Department of Mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. "Rather, the fundamental problem is that South American-native ungulates display detailed resemblances to a whole range of non-South American groups."

Following Darwin's first guesses, scientists thought these wacky animals were related to elephants, manatees, aardvarks and rodents, MacPhee said. "To break out [of] this confusing, contradictory round of possibilities, we needed a different probe, preferably molecular," MacPhee told Live Science in an email.

So the researchers screened bone samples. Long after DNA has degraded, collagen — a particularly durable protein — can be recovered from bone. But it's still difficult to glean information from it. Of the 45 specimens the team sampled for collagen, only five revealed any protein sequence information. The researchers then compared this with collagen DNA from a wide range of living mammals and a few extinct ones.

In every analysis, the researchers found that both of the extinct animals formed a sister group to perissodactyls, finally placing the oddballs onto the evolutionary tree.

MacPhee hopes that this method of pinning down the evolutionary history of extinct animals will greatly improve in the coming decades. Currently, researchers can access sequence information from fossil vertebrates that were living as early as 4 million years ago. Given how quickly techniques improve, this figure should be pushed back as far as 10 million years, MacPhee said.

There are also additional bone proteins that the researchers might be able to probe. One of the problems, however, is that if scientists decide to probe a new bone protein, there will be no comparable database with which to work, MacPhee said.

"But with more proteins, you begin to access more of the genome, improving your resolution on phylogenetic [evolutionary] trees," MacPhee said. "This is currently fantasy, but who would have imagined 25 years ago that ancient DNA studies would be where they are today?"

The new research is detailed today (March 18) in the journal Nature.

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology

- 6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.