How can you view the lunar eclipse? A skywatcher's guide.

Loading...

There will be a total eclipse of the moon on Saturday (April 4), and it will be visible over all of the Pacific Ocean and much of the adjacent mainland.

Skywatchers in Asia and Australia will see the first total lunar eclipse of 2015 on Friday evening (April 3) after sunset, while observers in North and South America will see it Saturday morning just before sunrise.

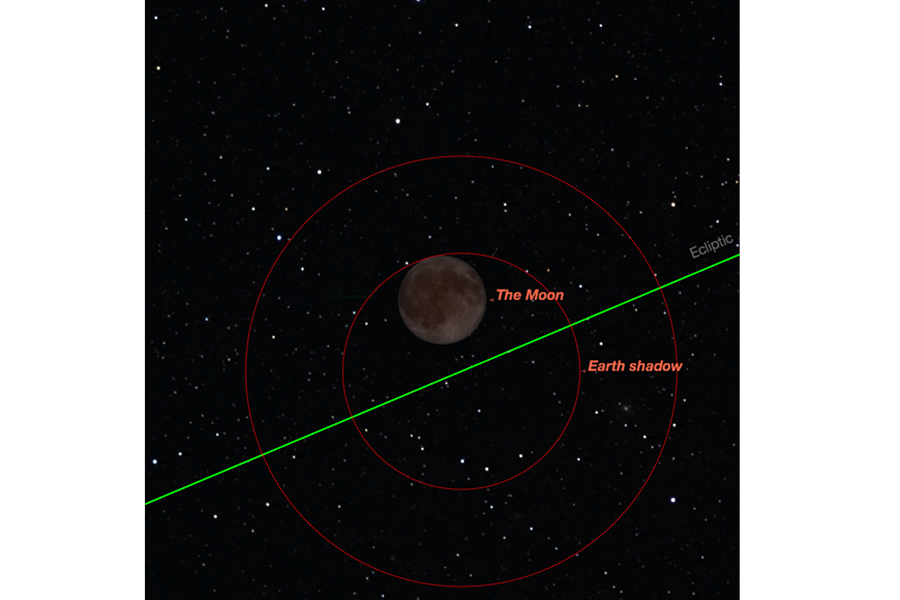

A lunar eclipse occurs when the moon passes through Earth's shadow. Because the moon's orbit is tilted, most of the time the moon passes above or below the Earth’s shadow, and no eclipse occurs. [Blood Moon Total Lunar Eclipse of April 4 (Video)]

An eclipse can only occur when the moon is close to the points in its orbit where it crosses the ecliptic, the sun's path around the sky. Eclipses in 2015 are therefore limited to the months of March, April and September.

We had a total solar eclipse on March 20 and will have a partial solar eclipse on Sept. 13 and another total lunar eclipse on Sept. 28. The area from which the September lunar eclipse will be visible is almost the exact inverse of this week's eclipse, so if you live in a part of the world where you can't see the April eclipse, you will have better luck six months from now.

Many people have the mistaken belief that the moon's phases are caused by the Earth's shadow falling on the moon. In fact, the Earth's shadow is nowhere near the moon except when the moon is full. The phases are caused by the varying angles from which the sun shines on the moon, and have nothing to do with the Earth.

Because of the size of the light source, the sun, the Earth's shadow has two parts. The central dark part where the sun’s light is totally blocked is called the umbra, while the outer lighter part of the shadow caused by the sun's disk being partially covered is called the penumbra. These are shown by two concentric rings in the first illustration. The moon is moving from west to east (right to left in the Northern Hemisphere). Even in the umbra, the moon is rarely completely dark because of the light from sunrises and sunsets around the world being refracted inward by the Earth's atmosphere.

The moon first enters the outermost, palest part of the shadow, called penumbral first contact or P1. This part of the shadow is so faint as to be invisible with the naked eye. As the moon slowly moves eastward into the shadow, the shading becomes more obvious. The point where the moon enters the darker umbra is calledumbral first contact or U1. At this point it will look like a tiny bite has been taken out of the disk of the moon.

The point when the moon is first completely immersed in the umbra is called umbral second contact or U2. The point when the moon begins to emerge from the umbra is called umbral third contact or U3. Because in this eclipse the moon just barely makes it into the Earth’s shadow before it starts to emerge again, the time between U2 and U3, called totality, is very short, only 4 minutes and 31 seconds. By contrast, totality in the Sept. 28 lunar eclipse will last 1 hour, 11 minutes, and 56 seconds.

It is during totality that the moon takes on the characteristic copper color of a lunar eclipse. This color has caused some people to call a lunar eclipse a "blood moon." Because the moon will be in the shallowest part of the umbra, I don’t expect to see much color in this eclipse — certainly not a blood red. [Must-See: Best Skywatching Events of 2015 (Infographic)]

The last two important times in this eclipse are umbral fourth contact (U4), when the moon passes completely out of the umbral shadow, and penumbral fourth contact (P4) when the moon is completely uncovered.

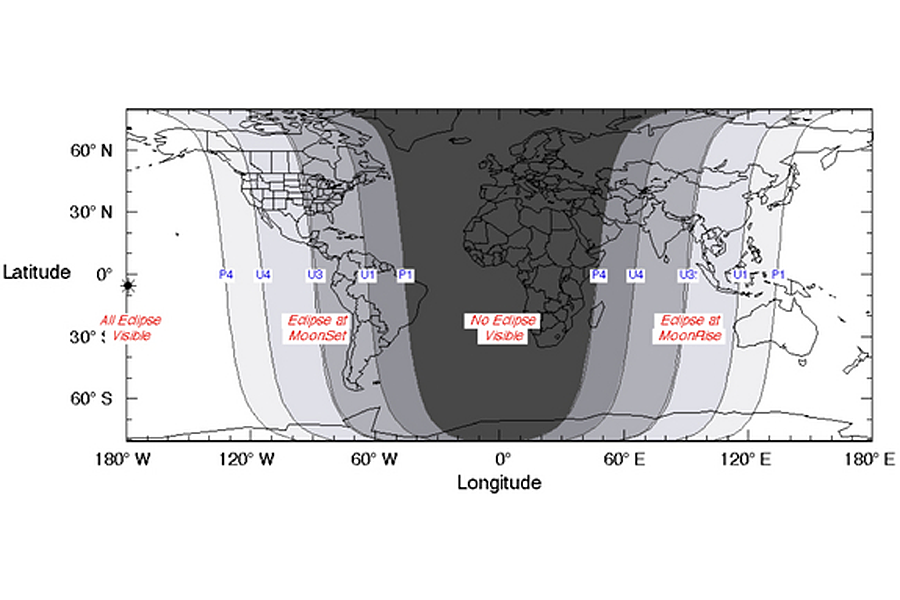

More specific information on where and when the eclipse will be visible is summarized in the accompanying chart, taken from NASA’s web site.

Areas of the chart without shading will see the full eclipse, weather permitting. Areas with dark shading will not see any eclipse, because the whole event occurs while the moon is below their horizon. The areas in between will see varying parts of the eclipse, depending on the local times of moonrise and moonset. The best locations are Australia, Oceania, eastern Asia and western North America.

Everyone who has the moon above their horizon during the eclipse will see the events at exactly the same time, in the absolute sense (Universal Time), but at different local times depending on their time zone.

For example, umbral first contact occurs at 10:15:46 UT everywhere. For an observer in the Eastern Daylight Time zone, this converts to 6:15:46 a.m. EDT, shortly before sunrise on Saturday. An observer in eastern Australia this will be 9:15:46 p.m. AEDT, a couple of hours past sunset on Saturday.

Here are the times of the contacts, first in Universal Time, and then converted for a few selected cities:

Contact UT New York Los Angeles Honolulu Sydney

P1 09:01 05:01 am 02:01 am 11:01 pm 08:01 pm

U1 10:15 06:15 am 03:15 am 12:15 am 09:15 pm

U2 11:58 07:58 am 04:58 am 01:58 am 10:58 pm

U3 12:02 08:02 am 05:02 am 02:02 am 11:02 pm

U4 13:44 09:44 am 06:44 am 03:44 am 12:44 am

P4 14:59 10:59 am 07:59 am 04:59 am 01:59 am

All times are on April 4, except for P1 in Honolulu (April 3) and U4 and P4 in Sydney (April 5). Every time there is an event like this one that occurs after midnight, some people miss it because they look for it a day late.

The latter parts of the eclipse will not be visible from New York or other locations in the EDT zone because the moon will have set, and the earlier parts of the eclipse will not be visible from Singapore and other locations in Asia because the moon has not yet risen. Check moonrise and moonset times for your location.

Lunar eclipses are completely safe to observe with or without any optical aid. Just be sure you have a low horizon. You don’t need a telescope; in fact, the eclipsed part of the moon is more obvious with the unaided eye.

Photographs can be made with almost any camera, but if you normally keep a filter on your lens, remove it because it may cause internal reflections. I once spoiled an entire set of lunar eclipse pictures by leaving a filter in place: I got two moons in every shot. Shooting through a window may also get you unwanted reflections. Because this eclipse occurs close to moonrise or moonset for many people, you should be able to get interesting foregrounds in your pictures.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing picture of the lunar eclipse Saturday or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments, and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- 'Blood Moons' Explained: What Causes a Lunar Eclipse Tetrad? (Infographic)

- Lunar Eclipse Beauty: How to Photograph the Moon (Gallery)

- Why The Moon Turns 'Blood' Red During Eclipse | Video

- Skywatching in 2015: 9 Must-See Stargazing Events

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.