Where did the first Americans come from? New clues from new studies.

Loading...

Who were the first Americans? Two research papers this week have arrived at contrasting interpretations.

One study, published Tuesday in the journal Science, proposes that the earliest Americans had singularly Siberian origins, crossing into the continent via the Bering land bridge in a single wave. Another, published Tuesday in Nature, suggests that some early Native Americans may have had genetic roots in Australia and its neighboring islands, a region known collectively as Australasia.

The peopling of the Americas is a matter of great anthropological and archaeological interest. We see evidence of unique culture on the continent over 10,000 years ago, but exactly how these populations arrived on the continent, and from where, has been debated for decades. Scientists generally agree that the first Americans crossed over from Asia via the Bering land bridge, which connected the two continents.

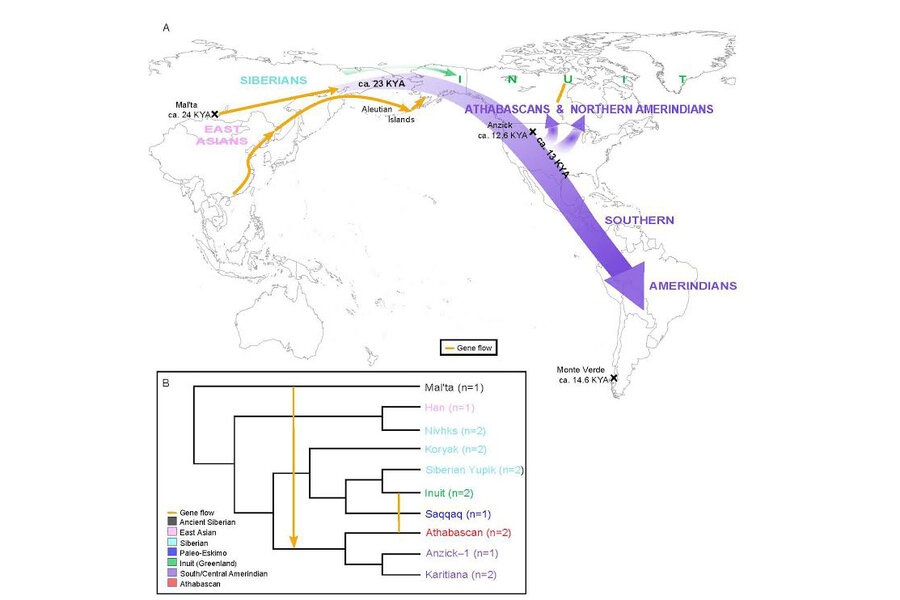

This exodus most likely began between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago. But some researchers have argued that Alaskan glaciers would have blocked entry into North America. The Beringia standstill hypothesis suggests that human populations would have remained stranded on this land bridge for some 15,000 years before ice melt finally allowed clear passage into the continent. From there, this main emigrant population would have split and diversified into many different first cultures.

Experts have noted that some early American skeletons, most older than 8,000 years, were found with physical features that seemed to contrast with those of historic and modern Native Americans. Some younger samples from South America also had these distinguishing traits.

“They have suggested that this morphology matches more closely with Australasian populations,” says Pontus Skoglund, who co-authored the Nature study. “But there has always been this question of how statistically informative this morphology is, and to what extent this actually reflects population relationships.”

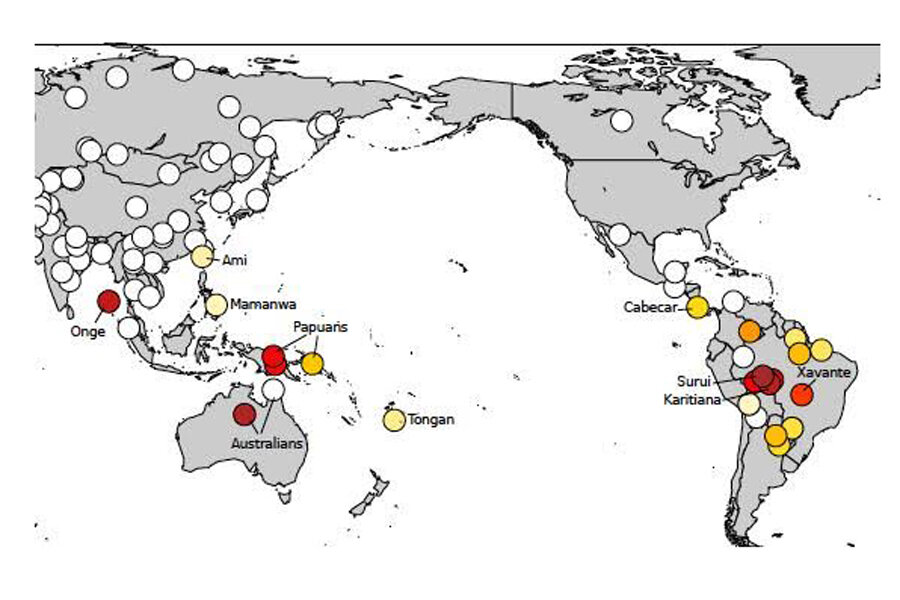

Using genomic data from Native American populations in South America and Central America, Skoglund and his colleagues found a surprising pattern. In some of these populations, they found a small degree of Australasian genetic ancestry.

“We found the peak of that signal in Brazil, which is also where people have suggested that the last populations with this morphology existed,” Skoglund says. “We don’t think that it’s likely that there was a population much more closely related to Australasians than to the Native Americans of today. But perhaps this is one step toward an explanation.”

A genetic link between Amazonian Native Americans and Australasians, Skoglund says, was previously unknown, and could have serious implications.

“I think almost no geneticists would have expected this,” Skoglund says. “What it tells us in terms of history, which is more important, is that there was a greater diversity of Native American ancestral populations than people previously thought.”

Skoglund and colleagues propose that, just before heading for the Americas, ancient Siberian populations could have mixed with an Australasian "Population Y." But the "how" and "when" are confined to mystery. The genetic data, Skoglund says, simply doesn’t tell us about that.

“My speculation is that there was a population quite closely related to Australasians in Northeast Asia around the time of the peopling of the Americas,” Skoglund says. “This population could have mixed with other populations to form the ancestral population of Native Americans. But there were perhaps multiple pulses of people into the Americas, and they had slightly different proportions of this ancestry. But which of the pulses came first and which different routes they took, we just don’t know.”

“The genetics have so far suggest that, in terms of ancient migrations, there was only a single one,” Skoglund adds. “There were a few additional migrations in the northern parts of the Americas, but those were more recent events.”

Similar genomic testing conducted by UC Berkeley geneticist Rasmus Nielsen supports the notion of a single migration. But it also challenges the Beringian standstill hypothesis in the process.

“We wanted to test it by dating the divergence time – that is, the split time between populations that now live in Siberia and East Asia, and the Native Americans,” Nielsen says. “How long since they had a common population that lived in Siberia or somewhere in Asia? Using a number of new techniques and data, we could date that relatively precisely to be about 23,000 years ago.”

Given this approximation, a Beringian standstill would have been impossible.

“The first people appear in the Americas 14,000 or 15,000 years ago,” Nielsen says. “That doesn’t leave time for a Beringian standstill. They had to split off about 23,000 years ago, move all the way through Asia, and cross the land bridge into the Americas in 7,000 to 8,000 years. So clearly there was no 15,000-year Beringian standstill. There could have been a little bit of a standstill, but nothing like 15,000 years.”

Nielsen’s research offers a broader view of settlement. Migration would have occurred in a single wave, Nielsen says, before splitting into two main populations.

“We see that mostly all Native Americans are descendants from a migration wave into the Americas, maybe 20,000 years ago,” Nielsen says. “You see the first unique American culture about 13,500 years ago, which spreads through much of the Americas. Right around this time, we see that the Native American population first began splitting up. We find two major groups – what we call the southern group and the northern group.”

Nielsen says his colleagues found just two exceptions to their findings. The study doesn’t account for Inuit populations in the north because they arrived later, bringing a distinctive culture with them.

“The other little exception, which was very interesting, was that we found signs of some genetic affinity between Brazilian Native Americans and Melanesians,” Nielsen says. “They were just slightly more related than they really should have been, given previous data.”

Like Skoglund and colleagues, Nielsen’s team found Australasian ancestry in modern Native American people. This led them to investigate another hypothesis for the peopling of America – one Paleoamerican hypothesis, which suggests that the first people to come to the Americas were not from Siberia, but rather Australians and Melanesians who traveled by boat.

“We find a hint of evidence for this hypothesis in some South American populations,” Nielsen says. “We managed to extract some DNA from ancient samples of supposed Paleoamericans, who display more Australian and Melanesian-looking traits. But do these individuals actually have any genetic affinity with Australians and Melanesians? When we tested that, we found that the answer was no. They are clearly related only to modern Native Americans. We think this is evidence of a later migration, perhaps one that happened on a coastal route along the western coast about 8,000 years ago.”

According to Nielsen and Skoglund, both studies rely on the same genetic signals. But different interpretations of those signals resulted in a few contrasting conclusions.

“They saw the exact same signal, and they have even stronger evidence for that signal,” Nielsen says. “They feel, as was our first hunch too, that this may be support for a Paleoamerican hypothesis. But if so, we should be able to see evidence of it in the ancient DNA, and we don’t.”

But interpretations aside, both studies share a common goal – to answer the basic questions about how the Americas were populated.

“This has been a really old, very controversial question with lots of different theories,” Nielsen says. “What we have shown is that, with the caveat of this little signal in the South Americas, we’re back at the most boring, most vanilla theory – one big migration that happened around 20,000 years ago. We have no support for all of these more fanciful theories.”