Did that asteroid have help wiping out the dinosaurs?

Loading...

The death of the dinosaurs may have taken a one-two punch combination.

A six-mile wide asteroid or comet that slammed into Earth 66 million years ago often takes the blame for the prehistoric beasts' demise. But it may have just kicked off the earth-shaking events.

The impact might have triggered catastrophic volcanic activity, which could have done more lasting damage than the impact itself, suggests a paper published Thursday in the journal Science.

“It’s one of the great mysteries of the history of the planet,” says study lead author and geologist Paul Renne in an interview. “How do you just wipe out such a large, diverse, and dominant kind of animal forever in the blink of an eye? It is an amazing thing.”

All non-avian dinosaurs and many other living species vanished from Earth at the close of the Cretaceous period, a moment geologists call the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary, or K-T boundary for short.

Scientists have long debated what caused this mass extinction. Dominant theories suggest a humongous space rock delivered the fatal blow when it struck the Gulf of Mexico.

But volcanism was another prominent idea.

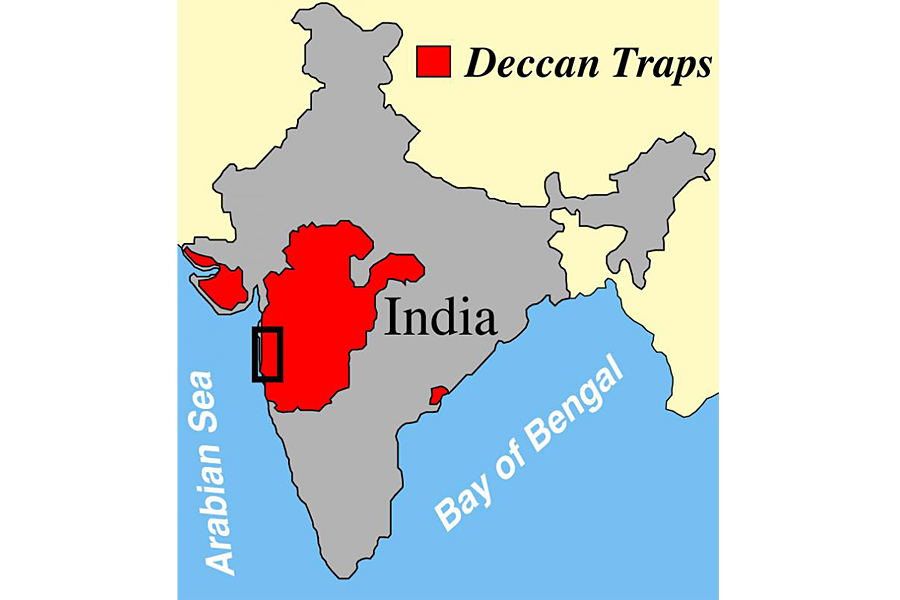

Some 9,000 miles away from the Chicxulub impact crater in Mexico, India holds one of the largest volcanic formations on the planet: the Deccan Traps. These massive lava flows, which the new paper dates more precisely than before, are the same age as Chicxulub.

Volcanoes can release devastating amounts of ash, lava, and gases when they erupt, which is why they have been blamed for other mass extinctions. In fact, a huge eruption about 201 million years ago likely led to the mass extinction that made space for the dinosaurs.

Researchers have fought for decades over what really killed off the dinosaurs. For Dr. Renne and colleagues, it comes down to timing.

“An impact the size of the one that happened at the K-T boundary, according to what we know, probably happens only once every billion years or so on Earth. It’s really improbable,” says Renne. “The notion that it should coincide with an outburst of volcanism – which is certainly not as rare, but also relatively infrequent – by chance, is really, really small.”

He continues, “When you’re dealing with coincidences that are highly improbable, you have to think about the idea that there may be a relationship between them.”

An extinction event big enough to wipe all the large vertebrates on land, at sea, and in the air (all dinosaurs, plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, and pterosaurs), requires something extraordinary.

“Major transitions in life on our planet are probably not caused by really simple events. They’re really complicated events. It’s all of these different phenomena acting together with all their feedback,” he says.

Earthquakes can induce volcanoes, Renne says, so his theory just takes that and scales it up. “If you just extrapolate the scale of volcanism and the scale of the seismic energy, it looks like that would work.”

The impact from the enormous asteroid (or comet – that's also hotly debated) would have created seismic energy about equal to a magnitude 11 earthquake on the Moment Magnitude Scale. For reference, the largest earthquake in 2014 was a magnitude of 8.2 in Chile. The Moment Magnitude Scale is logarithmic, and every 1.0 increase in magnitude releases over 30 times as much energy, so a jump of 2.8 means the shocks would have echoed back and forth through the Earth.

A big enough asteroid (or comet) could have jostled the planet down to its core, shaking the core-mantle boundary plume feeding the already active volcanoes in India and stimulating the massive eruptions of the Deccan Traps, which blanketed an area the size of Utah plus Nevada with lava flows more than a mile thick.

The lava and the ash produced could have caused local devastation, like volcanic material did in Pompeii, and the gases released would have had a global effect, says Renne, either an extreme warming or equally extreme cooling event.

Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane that erupted into the atmosphere could have raised the global temperature by several degrees. On the other hand, the sulfate aerosols could have blacked out the sun, leading to a global cooling. Or perhaps both happened on slightly mismatched timescales, causing intense climate fluctuations, Renne says.

Any of those scenarios would have forced all living things to adapt or die.

Renee and his colleagues proposed in April that this mass extinction may have required both the enormous impact and the massive eruption, working together. Their work to refine the age of the Deccan Traps has supported their hypothesis, says Renne.

They found that the Deccan eruptions accelerated and changed dramatically – and abruptly. "The transition from high-frequency, low-volume eruptions to low-frequency, high-volume eruptions suggests a fundamental change in the magma plumbing system," the researchers wrote in their paper.

And it all happened within 50,000 years of the impact at Chicxulub.

“It doesn’t mean that the volcanism changed 50,000 years after the impact,” explains Renne. The events could have been almost simultaneous, but the 40 Ar/39 Ar dating techniques his team used have a large margin of error – but still represent an improvement over the 100,000-year margin of error from previous studies.

“I can imagine a few thousand years being the timescale that these effects took to propagate and the magma to ascend from the mantle, but 50,000 years seems like an awfully long time,” Renne says. “If further work showed that it really did take that long, I think that we would have to consider some extra complications that we haven’t thought of yet.”

But the impact and eruption could also have happened “exactly at the same time,” Renne says.

Renne expects other scientists to challenge his findings, especially in light of the wide time window.

“Is this going to lay to rest the long-standing controversy about what happened? I don’t think it will,” Renne says. Too many researchers have made their careers around arguing one explanation or another.

Renne and his colleagues also aren't the first to say both the impact and the Deccan Traps caused the mass extinction. Last year, geologists argued that before the impact, volcanism had already weakened the dinosaurs. But they ultimately blamed the asteroid.

The extinction of the dinosaurs fascinates people of all ages – and with good reason, says Renne.

“Prior to the extinction, mammals were just tiny little rat-like things that wandered around and tried to avoid getting crushed or eaten,” he says.

“When the dinosaurs went away, opportunities in the ecosystem were opened up and mammals took off,” Renne says. “One could say, we are mammals and we would not exist – that humans would not have evolved had it not been for the dinosaurs’ disappearance.”

Clarification: The original version of this article explained the magnitude of seismic energy on the Richter Scale. The article has been clarified to use the Moment Magnitude Scale – the current standard scale used by seismologists.