When did people first arrive in South America?

Loading...

The earliest known Americans might have been living deep in South America significantly earlier than scientists thought.

Researchers had previously found clues indicating that people were living at the Monte Verde site in southern Chile as early as 15,000 years ago. But new evidence pushes that timeline even further back.

Stone tools, ancient fire pits, charred animal bones, and edible plant remains found during a new investigation into the site were dated between at least 14,500 and 18,500 years old.

Archeologist Tom Dillehay is no stranger to the Monte Verde site, nor is he a stranger to pushing the date of early human occupation in the Americas ever earlier.

Dr. Dillehay began research at the Chile site in 1977. At the time, scientists thought that the first Americans were what they call the Clovis people, large-game hunters who lived in North America beginning some 13,000 years ago. When Dillehay found evidence that people lived in Monte Verde some 14,500 years ago, a long debate ensued.

Now, Dillehay’s research team is pushing that date back thousands of years earlier yet again.

Initially Dillehay didn’t want to return to Monte Verde after finally debunking the "Clovis-first" model, “which is dead now,” he tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview.

But his team of archaeologists, geologists and botanists returned to Chile in 2013 when the country’s National Council of Monuments asked them for more investigation of the site.

“We went back, thinking we weren’t going to find anything,” Dillehay says. “It didn’t turn out that way.”

“We opened up the excavations even more, and we just kept finding things,” he says.

Although archaeologist Jon Erlandson of the University of Oregon, who is not involved in the study, told Science Magazine’s Ann Gibbons that, if correct, the new findings will “shake up both the archaeology and genomics of the peopling of the Americas,” some other archeologists aren’t sure the new findings are that groundbreaking.

“They’re earlier dates certainly, but for an outsider in these debates,” McMaster University archaeologist Andrew Roddick, who focuses on later archeological finds and cultures in South America, tells the Monitor, “I wouldn’t say that this will radically change my understanding.”

“This research may not be a thunderbolt out of the blue,” University of Central Florida archeologist John Walker, who is not connected to the study, tells the Monitor. “But it still is vindication of the idea that people living in South America had complex, interesting ways of life.”

The new findings not only represent a much earlier population of ancient Americans in Chile, but they also reveal that the community was likely much more sophisticated and mobile than previously assumed. The new findings are summarized in a new paper published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE.

“We don’t have a written record for this first chapter of humanity and the only way we’re going to get at it is to do this sort of interdisciplinary archeological work,” says Dillehay.

Early life in Monte Verde

Although glaciers had already begun to retreat in the area as the last Ice Age ended, the Monte Verde site was likely still quite cold and tundra-like at the time, explains Dillehay. In that environment, it would have been difficult to eke out a living.

“I think they were probably highly mobile,” Dillehay says of these early Americans. He describes the archaeologic record from 14,500 to 18,500 years ago as ephemeral. If there had been a population settled in the region long-term, there would have been a much more distinct archeological record, he says, with a more continuous and intense “flow of artifactual debris.”

So Dillehay thinks these people were at Monte Verde during the summer, passing through on a search for food or perhaps for other human groups.

These nomadic hunter-gatherers likely feasted on large animals, like mastodons or prehistoric llamas, and smaller game, like deer. The ancient animals’ bones were discovered in and around fire pits, broken and burned, suggesting the meat had been roasted.

Remains of edible plants were also found at the site, dating to the same time period. Burned stems suggest these people were cooking these plants too.

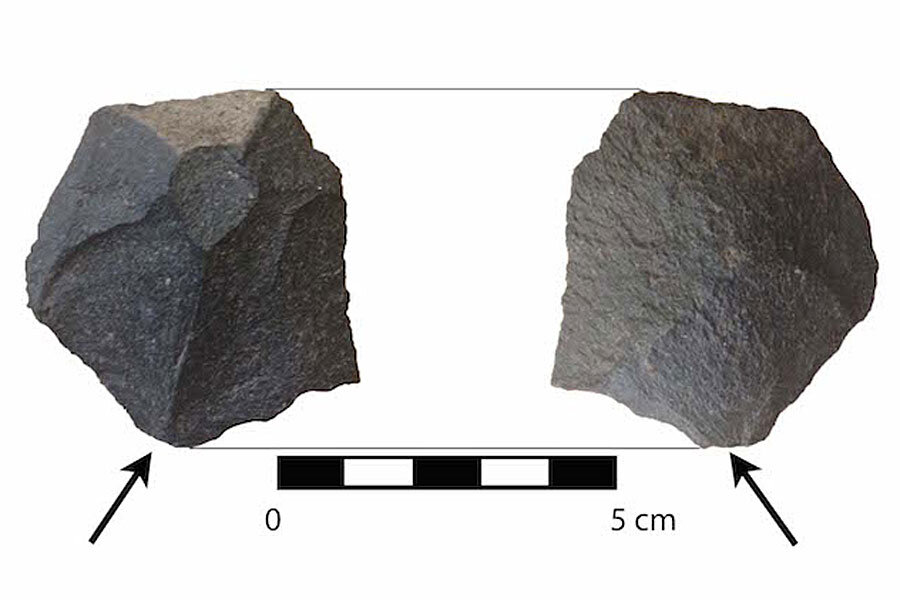

A number of stone tools were also recovered from the ancient site. Many of these stones were simple "unifacial" tools, with just one face of the stone worked to create a sharp edge. But some of the stones dated more recently show bifacial work.

A moving population

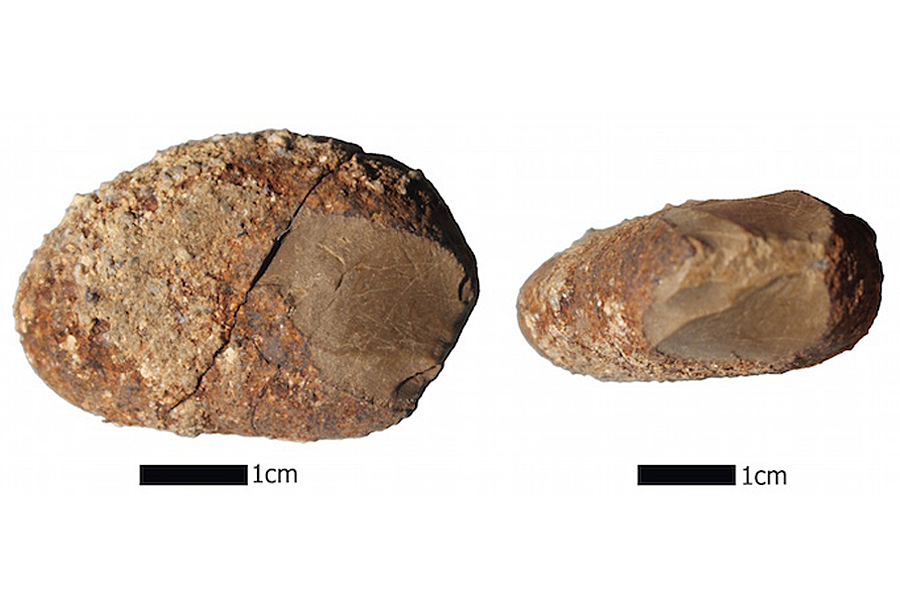

Intriguingly, some 34 percent of these tools were made from exotic materials, like limestone and white quartz, not originating in Monte Verde. Most of the rocks appear to come from the coast and some from the Andes mountains or beyond, says Dillehay.

Also, the coastal rocks, “they’re beach pebbles,” says Dillehay. “There’s no doubt about it.” He explains that the flat shape of the stones are distinctive to beaches.

Perhaps that’s where the people in Monte Verde were during the winters.

But they could have also gone further into the mountains at times. By about 19,000 years ago, says Dillehay, mountain passes were open and these people could have been traveling through the Andes.

Some of the food remains spotted at the Monte Verde site also originated outside of the region. Some of the plants didn’t grow in the area at the time, and the game likely wouldn’t have been found there either.

Although the area would have been getting more vegetated with the animals’ foods throughout deglaciation, it might not have been that way the whole time. These people might have had to hunt the game elsewhere.

“Why were they mobile? Some of it may have had to do with seeking food resources,” says Dillehay. But, he adds, “I always tend to think these people were a lot more social than we give them credit for.” Perhaps their movement was about creating social networks or exchanging technical and environmental knowledge, Dillehay says.

Dillehay’s previous work revealed a much more well-established group of people at the Monte Verde site after 14,500 years ago. These people had huts, used medicinal plants, and were more settled than their earlier counterparts.

With much less scattered artifacts, the population likely settled down for a longer stay at the site come some 14,500 years ago.

How did these people get to Monte Verde so long ago?

It’s often thought that humans migrated to the Americas by walking over the Bering land bridge that appeared during the last Ice Age. When the glaciers sucked up much of the world’s water, ocean levels sunk, revealing the land bridge stretching from Siberia to modern-day Alaska.

New research dates that movement to no earlier than some 23,000 years ago, which would mean Monte Verde’s first Americans would have had to hustle to get to Chile on Dillehay’s timeline.

Scientists believe it would have taken people many generations to move down through the Americas, as they didn’t have a direct path mapped out, and glaciers might have deterred their movements.

Some scientists have proposed that these early people moved southward along the Pacific coast, following a line of kelp forests that would have provided ample food. In this scenario, people might have island hopped along what has been dubbed a Kelp Highway.

Other ideas suggested have involved seafaring peoples, boating their way across oceans or between islands.

According to the Clovis-first theory, people trekked down from the land bridge through a corridor that opened up in central North America when the glaciers were retreating some 13,000 years ago. But, as the dates suggest, that explanation doesn’t match with Dillehay’s data.