Astronomers befuddled by mysterious flickering star

Loading...

An erratic star in the Cygnus constellation that’s been dimming and flickering in an unusual pattern has baffled scientists. In recent months, they have tried and tried to explain the unusual light behavior of KIC 8462852, from proposing that something is orbiting the star and thereby blocking its light as it passes in front of it, to suggesting that the flickers might be laser signals from aliens.

So far, none of the explanations are holding up to scientific scrutiny.

It doesn’t appear that the dimming is caused by a huge, orbiting array of solar panels, built by an alien civilization with an immense industrial capacity. Nor does the flickering seem to be coming from aliens who are trying to communicate with us, according to the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif., which looks for extraterrestrial life.

This fall, the Institute unleashed an array of telescopes on this distant star, about 1,400 light years away, to look for radio signals and laser pulses to try to explain the occasional 20 percent dimming of the light we see from the star.

It found nothing, and warned against succumbing to the temptation to rely on alien life to rationalize the inexplicable.

“Hundreds of years of astronomical study has taught us something important: Every time we've turned our telescopes to the heavens and found mysterious phenomena, there were folks who immediately assumed we had uncovered evidence of cosmic companions,” says Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at SETI, in a statement. “But each time, the truth turned out to be less exotic: we had discovered some previously unknown natural phenomenon."

In this case, scientists haven’t yet discovered a natural explanation.

The hypothesis that this bizarre dimming behavior is caused by a cloud of gas and dust that envelops young stars doesn’t hold up, as this one is too old for that.

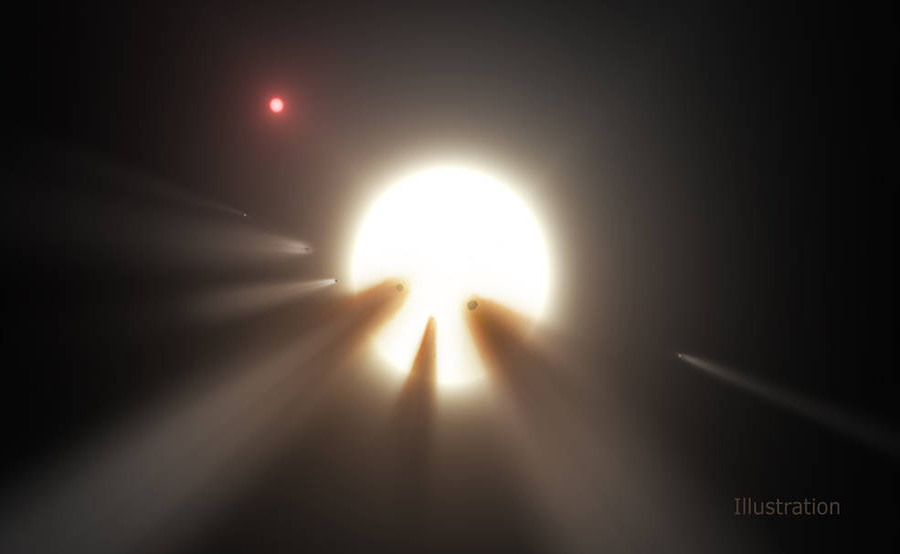

It also has been suggested that planets or a cluster of comets block out some of the light when they travel in front of the star, affectionately called “Tabby’s Star” in honor of Yale University astronomer Tabetha Boyajian, whose team published a paper in October describing the star’s unusual light pattern.

Dr. Boyajian’s team was among those who proposed the comet cluster as a feasible explanation.

But the hypothesis has been challenged by a Louisiana State University astrophysicist Bradley Schaefer. He studied 1,200 images of Tabby’s Star taken over a century starting in 1890 by the Harvard College Observatory to discover that this star, which is about 50 percent larger than Earth's sun, has been dimming over time.

So for the comets hypothesis to hold up, as the New Scientist recently reported, there would need to be 648,000 huge comets passing in front of Tabby’s Star constantly over a century. This is an unlikely scenario, Dr. Schaefer told the New Scientist.

“The comet-family idea was reasonably put forth as the best of the proposals, even while acknowledging that they all were a poor lot,” Schaefer told New Scientist. “But now we have a refutation of the idea, and indeed, of all published ideas."

It also has been deemed unlikely that the star's bizarre behavior is the result of planets orbiting the star and occasionally blocking its light. Even Jupiter-size worlds – more than 1,000 times bigger than Earth – would only block about 1 percent of the star's light, as SETI points out.

So what gives?

Science has yet to find out, so stay tuned.