How an ancient ocean ripped the surface of Pluto's moon Charon

Loading...

Why is the surface of Pluto’s largest moon cracked and fracturing? There’s something in the water, says NASA.

NASA scientists analyzed images captured by the New Horizons mission and concluded Charon likely had an ancient ocean below its surface that froze over time. The underground ice expanded, pushing the surface of the moon outward, “like Bruce Banner tearing his shirt as he becomes the Incredible Hulk,” NASA says in the press release.

When Charon was first imaged by New Horizons earlier this year, the moon's surprising complexity only added to the questions surrounding the bizarre moon.

Charon's surface has deep ridges, valleys, and other formations, including a system of chasms more than four times deeper and longer than the Grand Canyon.

“Charon is now emerging as its own world. Its personality is beginning to really reveal itself,” noted John Spencer, the deputy team leader of New Horizon's Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team, in July.

NASA’s new theory for Charon’s odd skin requires an ancient, subterranean ocean, hinted at in images taken by the Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on New Horizons.

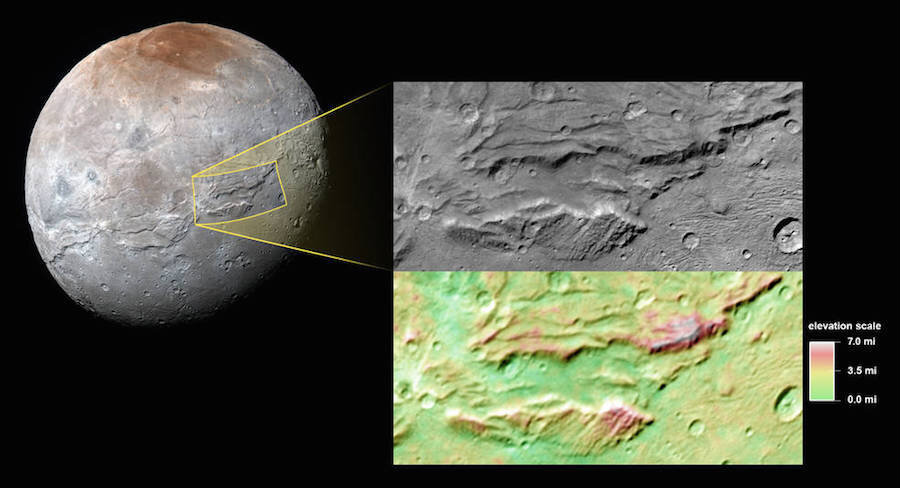

The LORRI captured an image of Serenity Chasma, one of Charon’s array of chasms, that allowed scientists to determine its size and shape. (A color-coded topography map of the chasm can be seen above.)

The surface of Charon is a rock-solid layer of ice, frozen down to the unthinkably cold temperature of -364 degrees Fahrenheit – only about a hundred degrees warmer than absolute zero. But that icy shell once protected a warmer interior, as NASA explained in the press release:

The outer layer of Charon is primarily water ice. This layer was kept warm when Charon was young by heat provided by the decay of radioactive elements, as well as Charon’s own internal heat of formation. Scientists say Charon could have been warm enough to cause the water ice to melt deep down, creating a subsurface ocean. But as Charon cooled over time, this ocean would have frozen and expanded (as happens when water freezes), lifting the outermost layers of the moon and producing the massive chasms we see today.

As the subsurface sea froze and expanded, slowly ripping apart the planet’s icy shell, it created a surface scarred with pull-apart basins very different from the crater-pocked skin of Earth’s moon.

The ridges and chasms that formed on Charon are some of the longest and deepest found in the solar system. Serenity Chasma (shown above) is 1,100 miles in length and 4.5 miles deep. By contrast, Earth's Grand Canyon is 277 miles long and roughly 1 mile deep, and Mars's Valles Marineris is more than 2,500 miles long and about 4 miles deep.

NASA’s New Horizon mission has catapulted the little-known world into national attention. Charon’s ancient ocean, long frozen, prompts interesting comparisons to the solar system's other icy moons, like Enceladus and Europa.

“We thought the probability of seeing such interesting features on this satellite of a world at the far edge of our solar system was low,” said Ross Beyer, an affiliate of NASA Ames Research Center, after the release of early images from Charon. "I couldn't be more delighted."