Dusty dinosaur bone sheds new light on perplexing giant predators

Loading...

After discovering a discarded dinosaur bone in the dusty drawer of an Italian museum, researchers have published new insights into the predatory – yet surprisingly endearing – Abelisaur.

The study, published Monday in the journal Peer J, also wades into the murky waters of Stromer’s Riddle, formulated in the 1930s by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer, which asks how so many different top dinosaur predators could have coexisted.

The work also highlights one of the understated services provided by museums: sheltering a treasure trove of potential discoveries, just waiting for the right person to come along.

“I simply stumbled upon a drawer with some specimens,” says coauthor Alfio Chiarenza, a PhD student in paleontology at Imperial College London, in a telephone interview with The Christian Science Monitor. “This femur called my attention because I recognized dinosaur features – especially carnivorous dinosaur features.”

Mr. Chiarenza was at the Museum of Geology and Paleontology in Palermo, Italy, delivering an invited talk at a paleontology conference.

The museum curators were “enthusiastic collaborators, having heard my presentation that morning,” Chiarenza says, allowing him and his colleague Andrea Cau of the University of Bologna to investigate the bone in question.

“This find confirms that at that time, in Africa, there was something particularly favorable for the existence of giant predatory dinosaurs,” Mr. Cau tells the Monitor in an email interview. “There is nothing comparable in modern world.”

Femurs can be particularly helpful in determining a dinosaur's size, and even fragmentary bones can hold a rich tapestry of information, says Chiarenza.

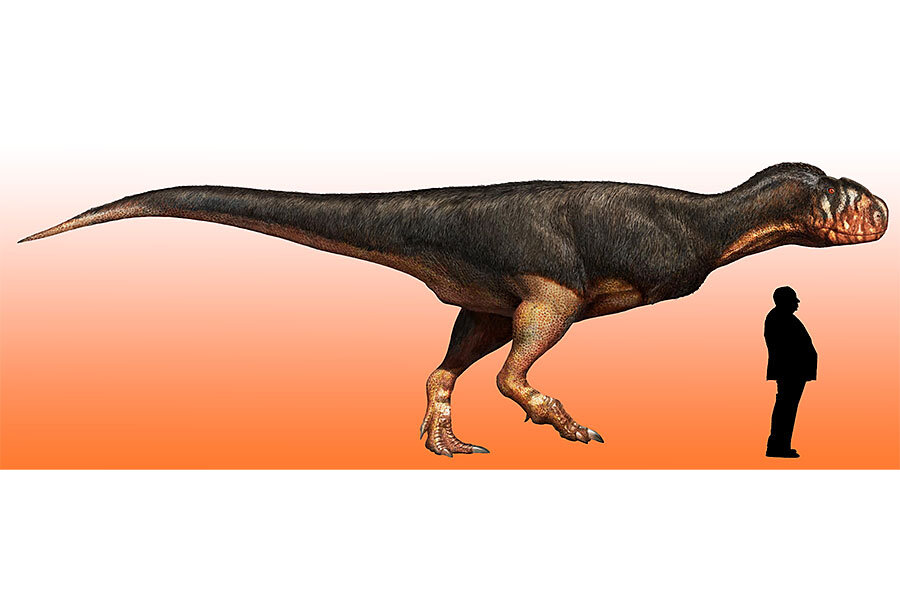

Using this forgotten bone, the researchers calculated that this animal was one of the largest Abelisaurs ever found. Moreover, while paleontologists already knew that Abelisaurs had existed in North Africa, they had never before found evidence that they had grown so large in this region.

This particular bone originated from the Kem Kem Beds in Morocco, an area shrouded in the mysteries of Stromer’s Riddle, with bones of myriad giant predatory dinosaurs all heaped together, suggesting they roamed the region at the same time.

One theory attempts to erase the paradox by blaming geological processes for jumbling up the fossils, but Cau and Chiarenza offer a different take.

“We reviewed the literature on dinosaur assemblages in North Africa and drew the conclusion that they may well have been confined to different environments,” says Chiarenza. “So, Abelisaur probably lived further inland, while others lived in more coastal habitats, or alongside rivers and lakes.”

Recent research into the Spinosaur, for example, “the one with the big sail and the long snout,” as Chiarenza describes it, suggests it was somewhat aquatic or amphibious.

When asked what has most endeared them to Abelisaur, both researchers mentioned the minuscule forelimbs, far smaller even than T. rex’s puny appendages.

“Evidently, their arms were not a necessary organ for their mode of life, more or less as a long tail is not particularly important for the human lifestyle,” says Cau.