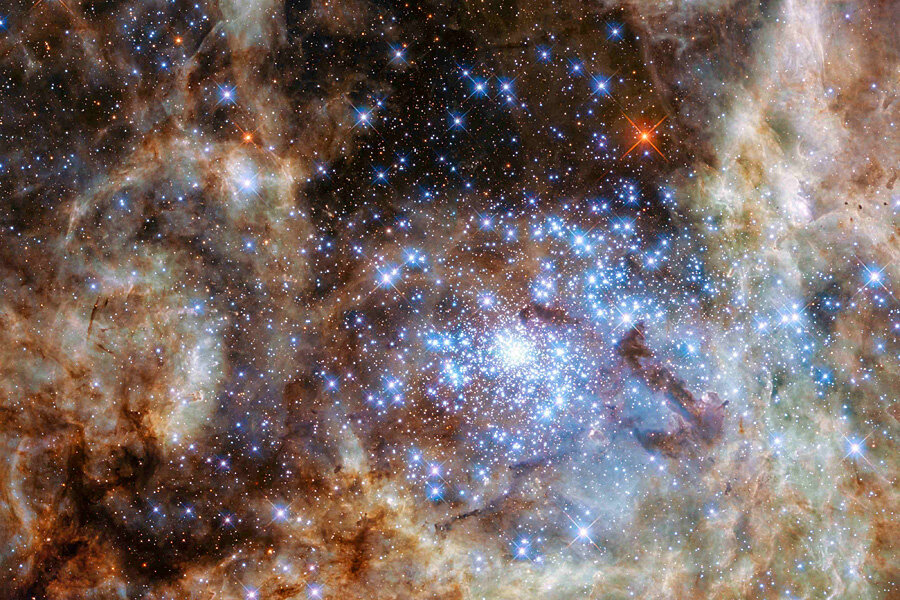

Hubble spots bright, massive stars in Tarantula Nebula

Loading...

The Hubble Telescope has once again made a massive find, literally, according to a group of astronomers who used Hubble’s unique abilities to analyze the Tarantula Nebula. Their study identified several dozen stars with masses more than 100 times that of the sun in a small star cluster named R136, located 170,000 light years away.

The Tarantula Nebula, or 30 Doradus, has been called a “star factory” by NASA and a “stellar nursery” by the authors of the study. The Hubble Telescope allowed astronomers to identify over 800,000 stars in the Tarantula Nebula by 2014 alone.

Nine of the super massive stars are clustered in a a very specific portion of the Large Magellanic Cloud called the Tarantula Nebula.

"The Tarantula Nebula is special in comparison to its neighbors for its size and brightness," study author Paul Crowther told The Christian Science Monitor by email. "Although our galaxy is much larger than the Tarantula Nebula, there are likely as many massive stars in that small corner of the universe as there are in the entire Milky Way galaxy."

“With respect to the Orion Nebula, it [the Tarantula Nebula] is 100 times bigger, 100 times more distant and 1000 times brighter,” Dr. Crowther says.

Scientifically, massive stars are stars that measure at least eight to ten times the mass of the sun. R136’s stars shine up to 30 times brighter than the sun as well.

Why are these beheamoths so bright?

"Because they are so massive, they are all close to their so-called Eddington limit, which is the maximum luminosity a star can have before it rips itself apart,” Crowther told the BBC. “And so they've got really powerful outflows. They are shedding mass at a fair rate of knots."

“Massive stars are actually quite rare,” said study co-author Saida Caballero-Nieves in an email to the Monitor. “However, they are still quite influential to their surroundings because they produce so much energy through radiation, strong winds and in some cases, explosive ‘deaths.’ ”

Scientists first detected the existence of these massive stars in 2010, when they discovered a humongous star they named R136a1, which is approximately 250 times the size of our solar system’s sun.

How these stars form is still a bit of a mystery, according to Dr. Caballero-Nieves. Since massive stars require a highly dense environment to form, the same gas cloud that facilitates their formation can prevent astronomers from observing it.

What’s so important about these massive stars?

Studying monster stars, which often come in closely tied binary pairs, could help astronomers unravel the mysteries of the relationship between black holes and gravitational waves.

Since the stars shine so brightly, they will also have short lifespans. Their deaths will result in black holes.

“We're currently using our observations to assess whether there are close binary stars amongst these monsters,” Crowther told the Monitor. “If so, they're the likely progenitors of binary black holes which have recently been detected to merge with LIGO [gravitational waves].”

Crowther told the BBC that the discovery of gravitational waves happened after large black holes merged. Those black holes were created by the demise of massive stars.

Like many other discoveries over the years, this one would not have been possible without Hubble’s ultraviolet observation capabilities.

“I think Hubble's top discovery is that over 20 years later, we are still uncovering fascinating discoveries of the Universe,” says Caballero-Nieves.

The massive star study will be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.