Australia was home to the world's oldest hatchet, archaeologists say

Loading...

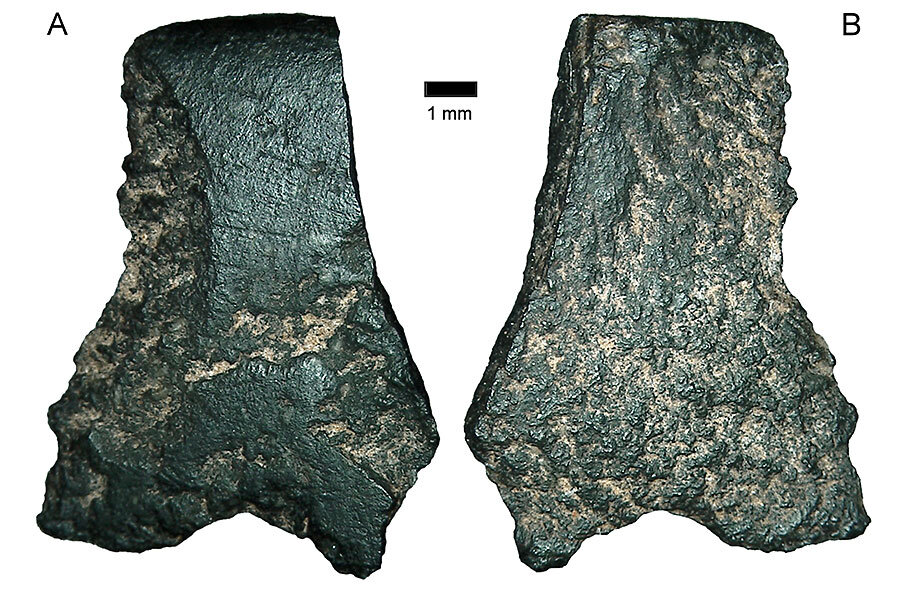

Fragments of the world’s oldest-known axe have been unearthed in Australia.

Having dated the artifact to between 46,000 and 49,000 years ago, archaeologists say it is the earliest evidence of a hafted axe – one with a handle – to be found anywhere in the world.

The discovery provides a possible solution to the enduring question of where axes originated, as well as putting the lie to assertions that early Aboriginal technology was a simple affair.

"Nowhere else in the world do you get axes at this date," lead archaeologist Sue O’Connor, of The Australian National University, said. "In Japan such axes appear about 35,000 years ago. But in most countries in the world they arrive with agriculture after 10,000 years ago."

The period in question puts the axe in Australia shortly after people are first thought to have arrived, about 50,000 years ago.

The researchers, who published their work Tuesday in the journal Australian Archaeology, say they know that these early settlers did not have axes where they came from. Nor is there evidence of axes in the islands to the north. In short, explained Dr. O’Connor in a press release, "They arrived in Australia and innovated axes."

The fragments were found in Windjana Gorge National Park, in Western Australia, by a team of archaeologists. Once they were lifted from their resting place, they were analyzed by Peter Hiscock from the University of Sydney.

"Since there are no known axes in Southeast Asia during the Ice Age, this discovery shows us that when humans arrived in Australia they began to experiment with new technologies, inventing ways to exploit the resources they encountered," said Dr. Hiscock.

Indeed, while part of the axe had already been uncovered by O’Connor in the early 1990s, this recent examination has thrown fresh light on the detail, including the fact that it was comprised of basalt, shaped and polished by grinding it against softer rock such as sandstone.

Such a tool would have been invaluable in the execution of tasks such as hewing down trees, tearing their bark off, or the crafting of spears. Yet, in spite of their utility, it seems as though axes failed to spread across Australia in the wake of human colonization.

"Axes were only made in the tropical north. These differences between northern Australia, where axes were always used, and southern Australia, where they were not, originated around the time of colonization and persisted until the last few thousand years when axes began to be made in most southern parts of mainland Australia," said Hiscock.

But of wider interest, perhaps, is the intriguing possibility that this axe really does represent the first cohort of axes to grace the human toolbox.

"The question of when axes were invented has been pursued for decades, since archaeologists discovered that in Australia axes were older than in many other places," Hiscock said. "Now we have a discovery that appears to answer the question."