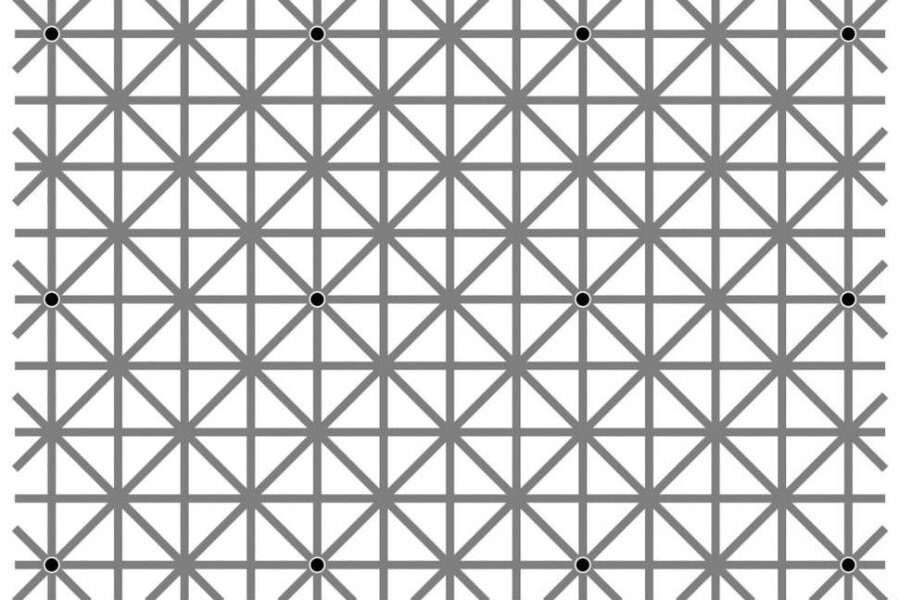

Why do we see ghostly, vanishing dots in this image?

Loading...

Most viral photos belong to one of the three members of the holy trinity of the internet: hilarious meme, adorable animal, and mind-bending optical illusion.

But while it's easy to explain the funny gif or a video of mewing kittens, the third type calls for a more vigorous scientific explanation.

The fascinating and more-than-a-little frustrating image currently taking the internet by storm was posted on Facebook by psychology professor Akiyoshi Kitaoka of Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan, on Sunday. From there, the image was tweeted by game developer Will Kerslake, where it made its way around Twitter before being picked up by other social media platforms. The photo went viral, with the original Facebook post being shared nearly 20,000 times at the time of writing this article.

The illusion in question shows a grid of crisscrossing gray lines. At certain crossings, there are back dots (12 in the original image) that seem to blink in and out of existence as the eye scans over the picture. Most viewers can see just a couple of black dots at a time. Only a very few can see all twelve at once.

For an explanation of the optical phenomenon, The Verge turned to Derek Arnold, a vision scientist at the University of Queensland in Australia. Dr. Arnold explained to the Verge that the main culprit is likely the mind trying to compensate for poor peripheral vision. Humans are able to concentrate on a single point very well, but vision outside that single point is blurry and indistinct. In order to fill in the gaps, the mind tries to interpret patterns and fill in the information that is not being directly seen with a best guess. Usually, this trait works remarkably well, but in the case of optical illusions like this, the system breaks down.

For this illusion, the mind sees the grid and fills in the area in peripheral vision with the rest of the of gray lines, missing the fact that the larger pattern contains black dots. Therefore, most people can see only the black dots that they are looking directly at, since the other dots are not present in the mental image provided by the mind's best guess as to the overall pattern. The dissonance between reality and perception triggers emotional response with the viewer, which led in this case the the rampant sharing of the photo as it quickly attained viral status.

"[Viewers] think, 'It's an existential crisis,'" Arnold told The Verge. "'How can I ever know what the truth is?'"

Optical illusions have long been popular candidates for internet virality. A picture of a dress in February 2015 sent waves across social media platforms as viewers saw the dress' colors as black and blue, white and gold, and sometimes both.

This particular illusion originated from the classic optical illusion known as the "Hermann Grid," which was first discovered and written about in 1870 by discoverer German physiologist Ludimar Hermann. In that illusion, a black area with a grid of white lines arranged as squares give the illusion that there are ghostly gray dots in your peripheral vision, according to Science Alert.

This new viral version of the Hermann Grid was originally discovered in the 1990s. Since then, it has been used in various scientific studies to better understand how visual perception works, particularly in the case of optical illusions. Dr. Kitaoka cited a 2000 article from the journal Perception in his original Facebook post that toyed with different variations of the Hermann grid to try to determine how different aspects of the grid – dot size, sharp or soft angles, etc., change how the illusion is perceived.

Despite decades of study on this and other optical illusions, scientists still disagree as to the neurological basis of why we perceive the way we do. But while we wait for science to catch up, there are plenty of meme-worthy optical illusions for internet users to share and explore.

With a couple of kitten videos thrown in, of course.