Nobel Prize in chemistry: Scientists building world's tiniest machines

Loading...

| Stockholm

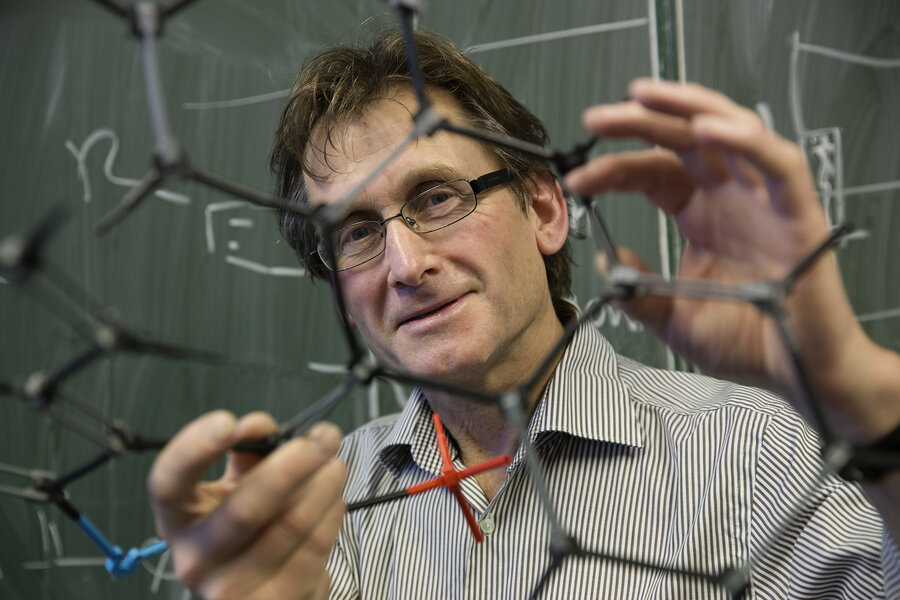

Three scientists won the Nobel Prize in chemistry on Wednesday for developing the world's smallest machines, work that could revolutionize computer technology and lead to a new type of battery.

Frenchman Jean-Pierre Sauvage, British-born Fraser Stoddart and Dutch scientist Bernard "Ben" Feringa share the 8 million kronor ($930,000) prize for the "design and synthesis of molecular machines," the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said.

Machines at the molecular level are 1,000th the width of a human hair and have taken chemistry to a new dimension, the academy said.

Molecular machines "will most likely be used in the development of things such as new materials, sensors and energy storage systems."

Stoddart has already developed a molecule-based computer chip with 20 kB memory. Researchers believe chips so small may revolutionize computer technology the way silicon-based transistors once did, the academy said.

It said the laureates' work has also inspired other researchers to build increasingly advanced molecular machinery, including "a robot that can grasp and connect amino acids" in 2013. Researchers are also hoping to develop a new kind of battery using this technology.

Sauvage, 71, is professor emeritus at the University of Strasbourg and director of research emeritus at France's National Center for Scientific Research. Sauvage's wife choked back tears as she absorbed the news. "Jean-Pierre won the Nobel prize," she said, her voice trembling as she spoke on multiple telephones at once ringing with news of the prize.

Officials at the University of Strasbourg, where Sauvage is a professor emeritus in the Institute of Science and Supramolecular Engineering, were overwhelmed and honored by the news, and said they were trying to reach him to celebrate his victory.

Stoddart, 74, is a chemistry professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. His daughter Alison said he was "absolutely ecstatic" at the honor.

Feringa, 65, is a professor of organic chemistry at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

"I don't know what to say, I'm a bit shocked," Feringa told reporters in Stockholm by telephone. "I'm so honored' and I'm also emotional about it."

Molecular machines are molecules with controllable movements, which can perform a task when energy is added, the academy said.

It said Sauvage made the first breakthrough in 1983 when he linked two ring-shaped molecules together to form a chain.

Stoddart took the next step in 1991 by threading a molecular ring onto a molecular axle, while Feringa was the first to develop a molecular motor in 1999 when he got a molecular rotor blade to spin continuously in the same direction.

In 1999, The Christian Science Monitor reported that some of the early discoveries in the field were by accident.

Chemist J. Fraser Stoddart's search for an antidote to a toxic chemical yielded a molecular rod and ring that fit together snugly, foreshadowing the molecular gadgets to come.

"We realized we were on our way to building something that could be a molecular abacus," says Dr. Stoddart, now a UCLA professor. "We started to see the beginnings of molecular designs."

Within a few years, advanced technologies such as electron microscopy gave Stoddart and others a clearer view of molecules and atoms. During the past decade, these technologies have helped scientists create nanotechnologies with both practical and profound uses.

Stoddart and colleague James Heath have built a nanoscale "logic gate" by manipulating molecules. These logic gates are analogous to those in today's computers, which are the heart of the computer - binary switches that direct electron flows and data. Building gates like these may lay the groundwork for molecular computers that are not only faster, cheaper, and more efficient than computers today, but also so small they could be woven into clothing.

The academy said the molecular motor is at the same stage now as the electric motor was in the 1830s.

The chemistry prize was the last of this year's science awards. The medicine prize went to a Japanese biologist who discovered the process by which a cell breaks down and recycles content. The physics prize was shared by three British-born scientists for theoretical discoveries that shed light on strange states of matter.

The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced on Friday, and the economics and literature awards will be announced next week.

The Nobel Prizes will be handed out at ceremonies in Stockholm and Oslo on Dec. 10, the anniversary of prize founder Alfred Nobel's death in 1896.

Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, wanted his awards to honor achievements that delivered the "greatest benefit to mankind."

___

Samuel Petrequin in Paris contributed to this report.