This star has a secret – even better than 'alien megastructures'

Loading...

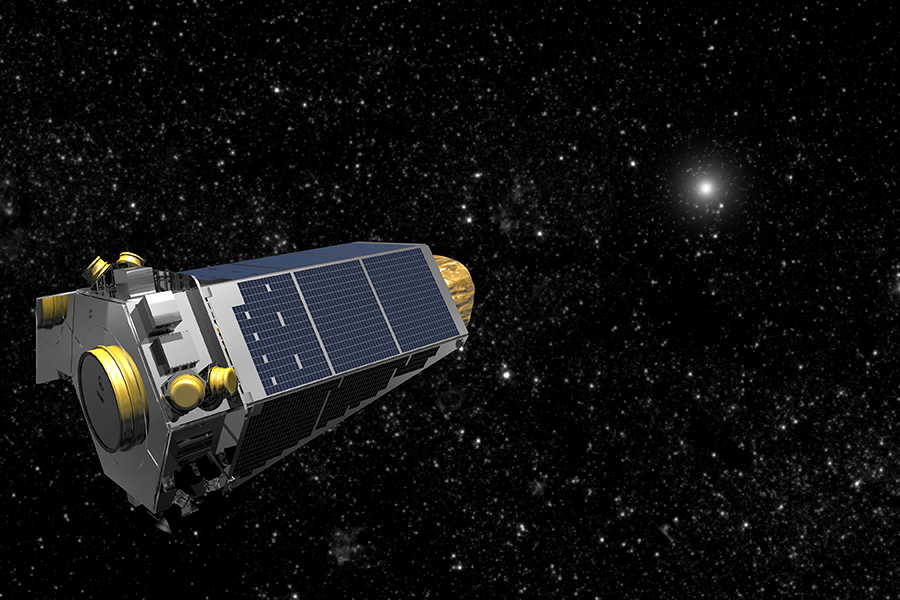

When Yale researcher Tabetha Boyajian first focused on the star KIC 8462852 via the Kepler Space Telescope in September 2015, she didn't know what to make of it.

The lighting of the star was mysterious – it was far too dim for a star of its age and type, intermittently dipping in brightness. Theories around Tabby’s star, as it was nicknamed, quickly piled up, with some scientists attributing the atypical lighting to surrounding cosmic dust or nearby comets. But more excitable space enthusiasts predicted alien activity, arguing that only orbiting alien structures could block a star’s light so effectively.

The so-called alien megastructure hypothesis persisted longer than most extra-terrestrial-based theories, simply because scientists had few alternative ideas to explain the star's peculiar blinking – until now. And the latest theory is almost as intriguing as the alien hypothesis.

Dr. Boyajian and her team weren't the first to spot the star: it was actually discovered in 1890. But their questions about the star's light pattern – and the subsequent alien-related theories – made the star, well, something of a star.

“We’d never seen anything like this star,” Boyajian told the Atlantic in October 2015. “It was really weird. We thought it might be bad data or movement on the spacecraft, but everything checked out.”

KIC 8462852's story became more intriguing in January 2016, New Scientist reports, when a comparison of the first image taken of Tabby's star, in 1890, with one taken in 1989 revealed that the star had dimmed 14 percent in the interim 100 years. And over one particularly confusing two-day period, the star dipped in brightness by 22 percent.

Tabby’s star kept scientists scratching their heads all last year. Volatility in light patterns are typical for young stars, but KIC 8462852 is mature.

“The steady brightness change in KIC 8462852 is pretty astounding,” Ben Montet, a scientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in an October statement. “It is unprecedented for this type of star to slowly fade for years, and we don’t see anything else like it in the Kepler data.”

Now, a team of scientists from Columbia University and the University of California, Berkeley, say they have found a reasonable explanation to KIC 8462852’s strange lighting.

“Following an initial suggestion by Wright & Sigurdsson, we propose that the secular dimming behavior is the result of the inspiral of a planetary body or bodies into KIC 8462852, which took place ~ 10-104 years ago (depending on the planet mass),” the three authors write in a study to be published Monday in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“Gravitational energy released as the body inspirals into the outer layers of the star caused a temporary and unobserved brightening, from which the stellar flux is now returning to the quiescent state.”

In other words, KIC 8462852 ate a planet sometime in the past 10,000 years.

The theory goes like this:

If KIC 8462852 did eat a planet – which is extremely rare in the space world, unless a collision pushed the planet out of its orbit – the star’s brightness would increase for a short period of 200 to 10,000 years as it burned up the planet (short in star time, that is). But once the burning was complete, the star would go back to around its original level of brightness.

So we could be looking at KIC 8462852 during its post-planet digestion, as it dims back to normal, write the authors.

And KIC 8462852 could have been a messy eater, leaving crumbs – aka orbiting planet debris – that periodically block its light.

“This paper puts a merger scenario on the table in a credible way,” Jason Wright, an astronomist at Penn State University, tells New Scientist. “I think this moves it into the top tier of explanations.”