When NASA moves out of low Earth orbit, will private companies move in?

Loading...

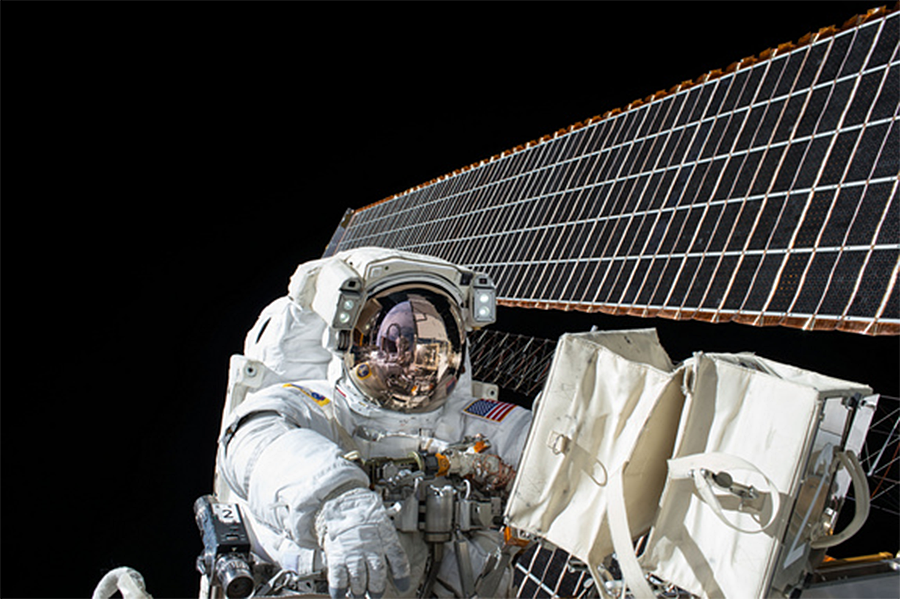

As it prepares to travel deeper into space in the next decade or so, NASA is urging private companies to leverage the investment it has made in low Earth orbit with the goal of commercializing this region of space near Earth.

Already astronauts aboard the International Space Station, an international crew of six people from the United States, Russia, Japan, and England, are doing research in microgravity for private companies like Merck, Novartis, and Procter & Gamble. But NASA says it wants to see this work expand broadly, and eventually, for commercial labs to operate in space independently of the ISS, a lab that NASA thinks it will be ready to leave by 2028.

"What I really hope is what we’re doing with these early commercial researchers, there will one day be way more than the ISS can handle,” Michael Read, who manages National Lab, an economic development program of the ISS, tells The Christian Science Monitor.

The microgravity environment of space is well-suited to research spanning from health to materials sciences. One project on the ISS now, for example, is experimenting with alloys, as lower gravity affects the physical behavior of these metals that are used extensively on Earth, from car parts to golf clubs to electronics and medical devices.

"The mere presence of gravity (such as on Earth) can mask other changes going on in an organism," Mr. Read tells the Monitor in an e-mail, "so by effectively eliminating that masking agent you can get a better understanding for the actual effects taking place."

Besides the dozens of private research projects the space agency is helping to coordinate, NASA’s recent win with privatizing low Earth orbit is a partnership with Texas-based private company NanoRacks, which has been delivering private experiments to the ISS for several years, and recently has developed a small research lab that will attach to the outside of the space station. It was delivered to the ISS this fall and will be installed in spring. It is the first commercial effort to offer private companies access to a microgravity lab outside of the ISS, says Read.

In a December meeting at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, the agency’s chief of human spaceflight, William Gerstenmaier, said that NASA is committed to moving humans deeper into space to the vicinity of the Moon, as ArsTechnica reported, and to do so will likely need to stop spending money on the ISS by 2028.

“We’re going to get out of ISS as quickly as we can,” Mr. Gerstenmaier said at the meeting.

“Whether it gets filled in by the private sector or not, NASA’s vision is we’re trying to move out.”

NASA now spends about $3 billion annually on the ISS, an expense that will rise to $4 billion by 2020, reports ArsTechnica. And according to Gerstenmaier, the agency cannot afford to support both the space station program and a human exploration program in deep space.

That’s where private companies will come in, the agency hopes.

“We’re way down the path to showing that there’s commercial viability on a large scale (in low Earth orbit),” says Read.

“You can help someone understand why it’s beneficial to do research there,” he adds, “but getting them to invest their own dollars, that’s beyond what the government can do.”