New 3-D projection technology allows 'printing in space'

Loading...

| Washington

One of the enduring sci-fi moments of the big screen – R2-D2 beaming a 3-D image of Princess Leia into thin air in "Star Wars" – is closer to reality thanks to the smallest of screens: dust-like particles.

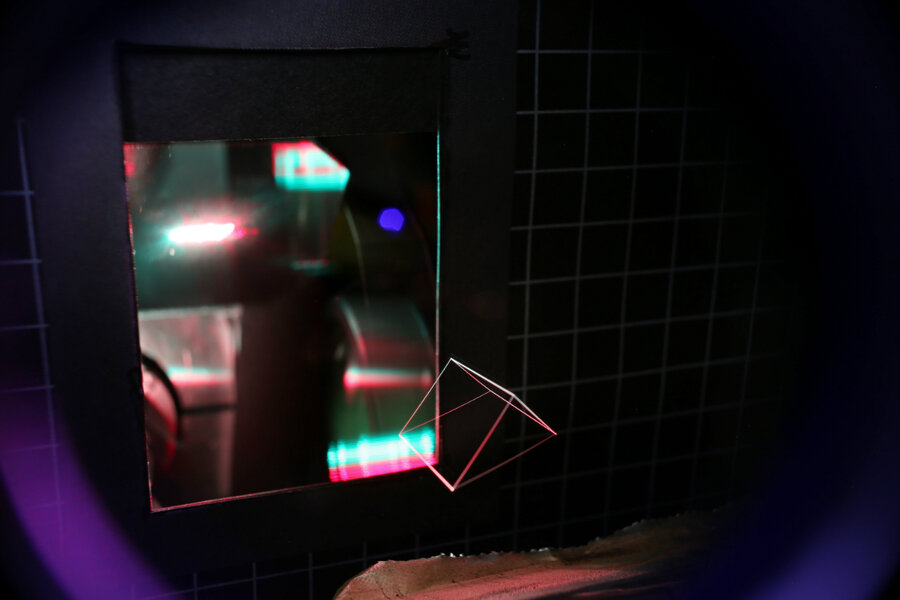

Scientists have figured out how to manipulate nearly unseen specks in the air and use them to create 3-D images that are more realistic and clearer than holograms, according to a study in Wednesday's journal Nature. The study's lead author, Daniel Smalley, said the new technology is "printing something in space, just erasing it very quickly."

In this case, scientists created a small butterfly appearing to dance above a finger and an image of a graduate student imitating Leia in the Star Wars scene.

Even with all sorts of holograms already in use, this new technique is the closest to replicating that Star Wars scene.

"The way they do it is really cool," said Curtis Broadbent, of the University of Rochester in N.Y., who wasn't part of the study but works on a competing technology. "You can have a circle of people stand around it and each person would be able to see it from their own perspective. And that's not possible with a hologram."

The tiny specks are controlled with laser light, like the fictional tractor beam from "Star Trek," said Mr. Smalley, an electrical engineering professor at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. Yet it was a different science fiction movie that gave him the idea: The scene in the movie "Iron Man" when the Tony Stark character dons a holographic glove. That couldn't happen in real life because Stark's arm would disrupt the image.

Going from holograms to this type of technology – technically called volumetric display – is like shifting from a two-dimensional printer to a three-dimensional printer, Smalley said. Holograms appear to the eye to be three-dimensional, but "all of the magic is happening on a 2-D surface," Smalley said.

The key is trapping and moving the particles around potential disruptions – like Tony Stark's arm – so the "arm is no longer in the way," Smalley said.

Initially, Smalley thought gravity would make the particles fall and make it impossible to sustain an image, but the laser light energy changes air pressure in a way to keep them aloft, he said.

Other versions of volumetric display use larger "screens" and "you can't poke your finger into it because your fingers would get chopped off," said Professor V. Michael Bove of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass., who wasn't part of the study team but was Smalley's mentor.

The device Smalley uses is about one-and-a-half times the size of a children's lunchbox, he said.

So far the projections have been tiny, but with more work and multiple beams, Smalley hopes to have bigger projections.

This method could one day be used to help guide medical procedures – as well as for entertainment, Smalley said. It's still years away from daily use.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.