DEA sued: Can feds create a fake Facebook account with your name and photos?

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

The Drug Enforcement Administration set up a fake Facebook account using photographs and other personal information it took from the cellphone of a New York woman arrested in a cocaine case in hopes of tricking her friends and associates into revealing incriminating drug secrets.

The Justice Department initially defended the practice in court filings but now says it is reviewing whether the Facebook guise went too far.

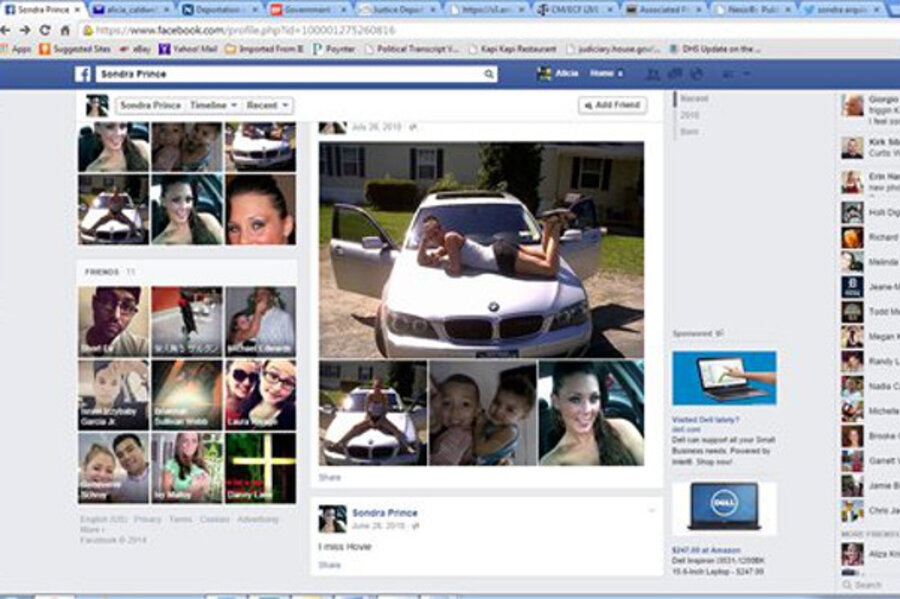

Sondra Arquiett's Facebook account looked as real as any other. It included photos of her posing on the hood of a sleek BMW and a close-up with her young son and niece. She even appeared to write that she missed her boyfriend, who was identified by his nickname.

But it wasn't her. The account was the work of DEA Agent Timothy Sinnigen, Arquiett said in a federal court lawsuit. The case was scheduled for trial next week in Albany, New York, although a mediator has now been selected for the dispute, court records show.

Justice Department spokesman Brian Fallon said in a statement Tuesday that officials were reviewing both the incident and the practice, although in court papers filed earlier in the case the government defended it. Fallon declined to comment further because the case was pending.

Details of the case were first reported by the online news site BuzzFeed News.

The case illustrates how legal standards of privacy are struggling to keep pace with constantly evolving technologies. And it shows how the same social media platforms that can serve as valuable resources in criminal investigations also can raise sensitive privacy implications that are at times difficult for law enforcement and the courts to navigate.

"How do you fit a new technology under your old rules? How do we think about a phone? How do we think about a Facebook account?" said Neil Richards, a privacy expert at the Washington University School of Law in St. Louis.

Arquiett, who is now asking for $250,000, was arrested in July 2010 on charges of possession with intent to distribute cocaine. She was accused of being part of a drug distribution ring run by her boyfriend, who had been previously indicted. She could have faced up to life in prison.

Court records show that in February 2011, Arquiett pleaded guilty to a charge of conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute and to distribute cocaine base. She was sentenced in January 2012 to time served and given a period of home confinement.

In the plea agreement Arquiett, who also was identified by the last names Prince and Arquiette, acknowledged that from 2008 to 2010 she was part of a drug conspiracy in Watertown, New York. The records also show she participated in jailhouse telephone calls with co-conspirators and at times made three-way telephone calls connecting jailed co-conspirators with others.

The court records do not show whether Arquiett agreed to testify against any other members of the conspiracy.

In a court filing in August, the Justice Department contended that while Arquiett didn't directly authorize Sinnigen to create the fake account, she "implicitly consented by granting access to the information stored in her cellphone and by consenting to the use of that information to aid in ... ongoing criminal investigations."

The government also argued that the Facebook account was not public. A reporter was able to access it early Tuesday, though it was later disabled.

A spokesman for Facebook declined Tuesday to comment on the dispute. Facebook's own policies appear to prohibit the practice, telling users that "You will not provide any false personal information on Facebook, or create an account for anyone other than yourself without permission."

Donald Kinsella, one of Arquiett's lawyers, declined to comment. Arquiett did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Arquiett said in her filing that she suffered "fear and great emotional distress" and was endangered because the fake page gave the impression that she was cooperating with Sinnigen's investigation as he interacted online with "dangerous individuals he was investigating."

The fate of Arquiett's fight against the government's use of her identity online is unclear. Law enforcement agencies routinely use fictitious online profiles in their investigations, including in cases of child pornography. But it's unclear how many other times a real person's identity has been used in this way.

Nate Cardozo, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil liberties organization, said the government's rationale was "laughable."

"If I'm cooperating with law enforcement, and law enforcement says, 'Can I search your phone?' and I hand it over to them, my expectation is that they will search the phone for evidence of a crime," Cardozo said, "not that they will take things that are not evidence off my phone and use it in another context."