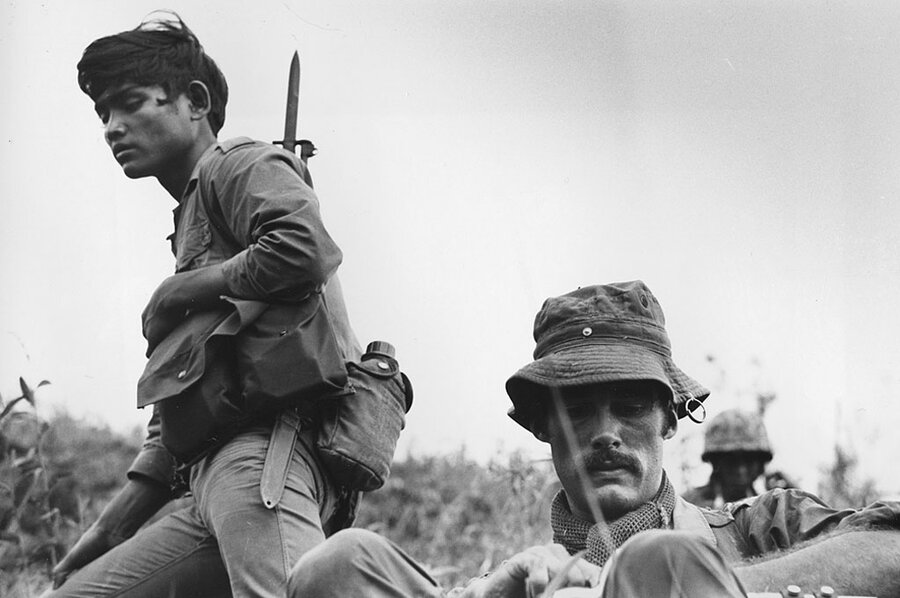

Southeast Asia: a correspondent's Vietnam revisited 35 years after the fall of Saigon

Loading...

| Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

For correspondents on the scene of the past half century of foreign wars, there never was anything quite like the decade of United States military involvement in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos from the early 1960s to "the fall of Saigon" on April 30, 1975. Call it the best of times, the worst of times, or both, but journalists had a measure of freedom, and often luxury, in those days that they never had in the Korean War or World War II – and certainly don't see in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Memories of jumping on US Army helicopters or lumbering C-130 transport planes bound for distant landing zones and airstrips remind those who covered the war of how easy it all seemed. One letter from an employer to the Joint US Public Affairs Office on the ground floor of the Rex Hotel in Saigon (the name by which the historic core of Ho Chi Minh City is still known), or two letters from editors willing to vouch for freelancers, were enough to get a press card good for military transport, for cheap dining in military mess halls, for shopping at post and base exchanges, and even for using the Army post office. And hotels, markets, bars, and restaurants of Saigon and other Vietnamese cities offered services at amazing discounts for those who changed their dollars for local dong at "the Bank of India" – the catchall name for the money-changers from India who operated behind the cover of bookstores and offices.

"We had incredible freedom in Vietnam and Cambodia," says Dan Southerland, a former correspondent for the Monitor and United Press International (UPI). Mr. Southerland, revisiting Phnom Penh as executive editor of Radio Free Asia, a US government network that broadcasts news into Asian countries, compares the ease with which journalists ranged over the region with the practice now of "embedding" reporters with military units if they wish to cover whatever they're doing.

"What you need is both embedding and the outliers," he says, meaning news organizations should rely on reporters both within and outside military units. In general, he says, "I think they are doing the best they can."

Others, however, strongly disagree. "My instinct is not to get embedded," says Simon Dring, who reported on Vietnam for Reuters in the 1960s. He sees reporters as having done some of their "best work" in Iraq and Afghanistan beyond the scope of military control. "It is very dangerous," he observes. "They take tremendous risks. They do fantastic reporting."

Journalists who covered wars in the states of former French Indochina faced many of the same risks but seem to have more of a sense of camaraderie than do those from later conflicts in Eastern Europe, Central America, and the Middle East. They share nostalgic memories of fine French menus mingled with the adrenalin rush of rocket attacks and firefights, distant battles and close-up coups.

Even mentions of the daily military briefings in Saigon, the "5 o'clock follies," evoke stories of tiffs with briefing officers, of reporters noted for relying more on the word of MACV, the Military Assistance Command Vietnam, than on firsthand views from the scene. Those days, old-time correspondents concede, have disappeared into the mists of history while US forces wage war in very different environments, in which security is never certain and adventurous, off-base night life largely nonexistent.

Danger lurked in different forms, often where least expected, in Vietnam and Cambodia, where 69 correspondents, photographers, and local interpreters and assistants were killed. The first casualty was the female photographer Dickey Chapelle, killed by shrapnel set off by a booby trap in the Mekong River Delta in November 1965. The last was another photographer, Frenchman Michel Laurent, killed on April 28, 1975, two days before the surrender of the US-backed government in Saigon.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia's long-reigning hereditary leader, described his country as "an oasis of peace," and it still seemed that way after he was overthrown while drumming up support in Moscow and Beijing. Hitching rides up well-traveled "Route 1" between Saigon and Phnom Penh, chatting on the way with CIA-financed Cambodian forces, I was relieved to be away from the morass of Vietnam.

Here was major news that was simple to cover. You could go to Cambodia, accompanied by a local assistant, in an old Mercedes-Benz taxi, picked up behind the Hotel Royale, listening to American pop music on the Armed Forces Vietnam Network. Down the road, you might hear the crump of artillery or even staccato sound of small-arms fire, interview a few villagers about the spreading war, return in time to file a story by cable or telex, and then relax over dinner by the Royale pool. Nor was I all that concerned when I ran into North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge troops while driving far south of Phnom Penh with a Canadian TV team led by globe-trotting correspondent Bill Cunningham at the beginning of April. They let us go with propaganda leaflets, in Vietnamese and Khmer, after Cunningham showed his Canadian passport – and did not ask to see my US passport.

Another day, another tale to tell around the Royale pool. Another easy story – meriting headline, with photo, across the top of Page 1 of the next day's Washington Star.

It was all deceptively easy, and then suddenly it got dangerous.

Several days later, returning from the scene of a massacre in the eastern Cambodian town of Prasaut, where I counted the bodies of 90 Vietnamese refugees gunned down overnight by Cambodian soldiers in a barnyard, I ran into photographers Sean Flynn and Dana Stone on motorcycles, at a roadside stand. An old woman, through my interpreter, had told us the Khmer Rouge were "over there," but Flynn and Stone drove off, eager to get photographs, while I returned to Phnom Penh with my story on the massacre. They were never seen again.

"In Cambodia, we just couldn't believe how bad it was going to be," says Southerland, who saw Flynn and Stone that day, too.

We all have special memories of tragedy. I never saw my interpreter again after visiting Cambodia for the last time in 1974, when peasants told us the Khmer Rouge were terrifying the populace, sawing off heads with sugar palm leaves. British photographer Tim Page, wounded four times, has been searching for years for clues as to what happened to Flynn and Stone. Mr. Page responds indignantly to claims by four young Australians that they dug up the probable remains of one of them north of Phnom Penh. He suspects the four want to capitalize on the mystique surrounding Flynn, son of the swashbuckling actor Errol Flynn, and feels especially disdainful after the US Joint Prisoners of War, Missing in Action Accounting Command in Honolulu dismissed the find.

Such episodes, though, seemed isolated, almost like accidents in a war that ebbed and flowed. There was no censorship, no worry about officials blocking or slowing the flow of stories or photographs. Nor did correspondents in those days have to worry about Internet messages or calls on cellphones. You never called your office, and you waited for the surprisingly efficient postal services in Saigon, Phnom Penh, or Vientiane to deliver cables the next day on the fate of the pieces you had filed the night before.

Not that reporters were totally free. MACV withdrew accreditation from journalists for violating an embargo imposed on plans to withdraw from Khe Sanh after the 77-day siege was broken. Nor did reporters see the "secret air war" over portions of Laos and Cambodia. The bombing of the Ho Chi Minh trail down which North Vietnam shipped men and supplies to the South remained a mystery. Matt Franjola, who covered Vietnam and Cambodia for UPI and the Associated Press, is sure of one thing.

"The Americans never had any clue of how to run this war," he says. "Every generation makes the same mistakes as the one before. The Americans have no idea what they're doing in Iraq and Afghanistan either."

•Donald Kirk covered the region for the Washington (D.C.) Star and the Chicago Tribune, wrote articles for The New York Times Magazine and others, and is the author of several books about that period, most recently "Tell It to the Dead: Stories of a War" (1996).