A kids' backyard playhouse and their arsenal of weapons plays on a granddad's memories

Loading...

| Bethany Beach, Del.

The house outside may be facing the end of its days. It presents a skeletal image now of what it once was. Only one wall remains, the one in the back; the roof is gone, probably blown off during a storm. This enabled the pines to deposit about an inch of their needles onto the floor, a mere four and a half feet square. Now, when the sun comes through the trees after a rain they shimmer like new copper, or a hoard of fool’s gold.

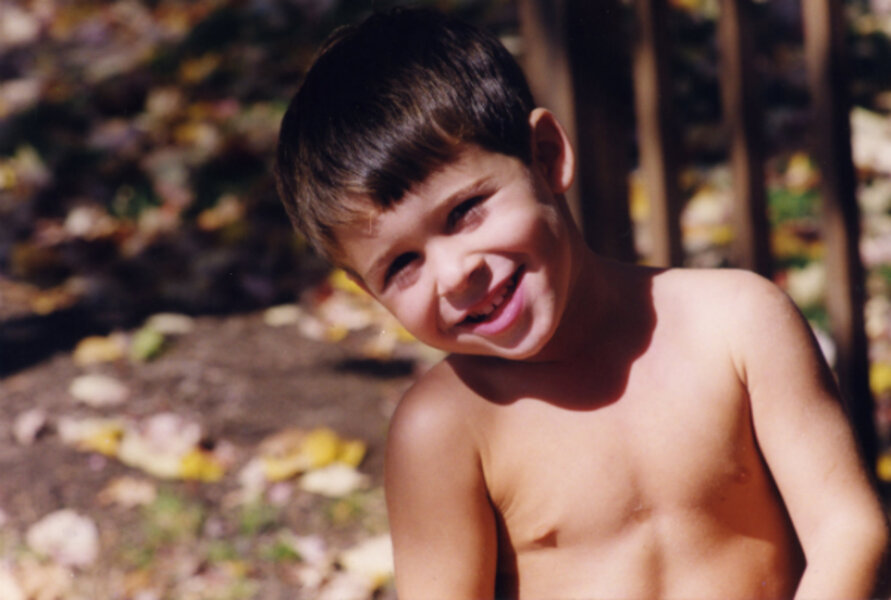

It was to be Nicholas’s retreat from the world of adults. His father, Pat, and I, built the thing on four posts, to hoist it about three feet off the ground, necessary in this low terrain so close to the sea. We attached a three-step ladder to get into it. When we finished we told Nick to share it with his younger brother, Stefan, my second grandchild, and with his cousins, my three other grandchildren, when they come down here to enjoy the beach with us. Nicholas, when he got a little further on in his life, didn’t bother with it much. “It’s for kids,” said No. 1 Grandson, as he pushed off on his skate-board down the road toward the beach, lugging his surfboard.

Nick doesn’t know that I identify him in my mind by a number. I got the idea from Charlie Chan, the fictional character in old movies, a Chinese American detective with a frozen, unhappy smile, yet operating effectively in an American milieu. He was like Confucius, wise and out of his time. Charlie called his first born “No. 1 Son,” which suggests to me that he expected others would follow.

After Nick, came Stefan, No. 2 in our family; Lily followed as No. 3; then her brother Finnegan, No. 4, and finally No. 5, Lukas: what a talker! I don’t tell any of these children about their numbers. I do it because it just helps me keep their names adhered to their faces.

They all played in and out of the house over the years, rough and loud sometime. Stefan, for instance, once took a hammer and a bag of nails and pounded them all into this playhouse; maybe he thought his father and grandfather had built a rickety unstable retreat. We didn’t.

One of Stefan’s siblings, bright Finnegan, suggested that all those nails might draw lightening our way. Stefan gave thought to that, and the next time I saw him with the hammer in his hand he was sitting on the ground breaking up a concrete block. Why? Maybe he felt a need to create something: rubble, perhaps.

Lily (No. 3) favored sedate tea parties. I once saw her climbing into the house with both Stefan and Finnegan trailing behind her with crockery in their hands. Lily poured her tea, and peace reigned. She calmed the boys with her softness and her tea – for a while at least, until the boys’ friends showed up in the yard and they all began shooting one another. Together they had an arsenal that would have impressed Muammar el-Qaddafi.

They had pistols, machine guns, hand grenades to throw at each other, rubber knives, even scimitars, ancient weapons to stab and slash with long blades made of pure sponge. One day, while sitting on the porch of the main house, I kept hearing “Bang! Bang! Bang! You’re dead!” Over and over.

I’ve never felt comfortable having weapons around the house, so I never did. Even fake weapons such as ours. More than once I said to myself, “It’s not a gun. No, it’s not a gun; it’s a symbol of a gun. A toy. Harmless. Yes, right?” But occasionally I would shout at them: “Don’t shoot so loud,” I’d say. “You’re disturbing the peace!”

There came the moment when my mind took a turn in a different direction: I began to think the toys were not completely harmless; they were everywhere: floating through the Internet; on display in shops all around our town.

I looked in on Wikipedia and learned that in our country more people own firearms than those in any other country in the world. Also I learned that 40 percent of our nation’s households have guns in them, one or more. Comforting?

I’ve been in many countries as a travelling journalist. I’ve watched children playing on green fields and in dry rust-colored spaces in Asia, South America, the Middle East, Africa, and other places distant from here. But I have never seen them waving plastic guns that look very much like the real thing. More often than not, the noise, the joyous shouts and screams were made by kids chasing and kicking soccer balls.

One day, having heard “Bang! Bang! Bang! You’re dead!” too many times around my house, I decided to seize their arsenal. And, unfortunately, their pleasures. “No more guns around here, I declared.” And they disappeared, just like that. The next day I uncovered one or two of them, one that looked very much like an AK-47. They were stashed behind a tree. With great ostentation I threw them in the trash. And I discovered some more in the house outside, which encouraged me to tear it down. But no, the smaller ones, Finny and Lukey are still in and out of it.

Maybe I’ll give it another year or so.