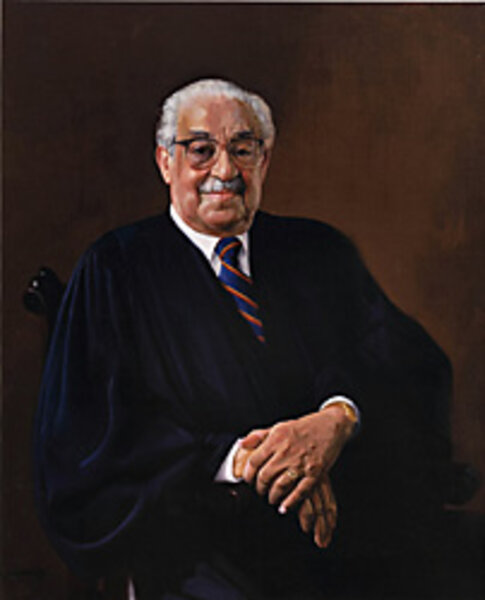

Thurgood Marshall: Civil Rights Champion

Loading...

You'd probably groan if you had to memorize long portions of a complicated document as punishment for cutting up in class.

The young Thurgood Marshall wasn't too happy, either, when teasing his classmates and joking around got him sent to the school basement to learn huge chunks of the US Constitution.

But when Mr. Marshall grew up, he could laugh about the experience. By the time he left that school, he said, he knew the whole Constitution by heart.

It's a good thing he did, because he became a very influential person in US history – as a famous civil rights lawyer and later the first African-American justice on the US Supreme Court – and the Constitution was a major inspiration in his life and career.

Civil rights lawyers specialize in protecting the freedoms that the Constitution guarantees to American citizens. Civil rights law focuses especially on the rights provided by the 13th and 14th Amendments.

Mr. Marshall's most famous civil rights case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kan. (the "v." stands for "versus," the Latin word for "against"), was tried before the US Supreme Court.

It was actually a combination of five cases that originated in lawsuits by black students and their parents challenging legal segregation, or separation by race. In the 1950s, when these cases began, some states still had laws requiring black kids and white kids to attend separate schools.

Although these states claimed that their laws followed a doctrine known as "separate but equal," which the court had approved in an 1896 case, anyone could see that the education black children received was really not equal but second-rate. They often had to walk miles to get to ramshackle school buildings where the outdated books were falling apart, while white students generally rode comfortable buses to their well-equipped schools.

Mr. Marshall and the other attorneys representing the parents and students in the lawsuits wanted the Supreme Court to declare that the state segregation laws were unconstitutional.

They argued that the laws violated a clause in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution requiring "equal protection of the laws."

They also tried to convince the court that forcing black children to attend segregated schools made them feel inferior and denied them the opportunity to reach their full potential.

Growing up in the early 20th century, Mr. Marshall knew firsthand how it felt to experience segregation and discrimination.

Born July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, he was named Thoroughgood after his paternal grandfather, but in second grade he shortened it to Thurgood because he thought it took too long to spell a name with so many letters.

Four years before Mr. Marshall was born, many black people in Baltimore held a boycott of local trains and steamships to protest new Maryland laws requiring segregation of "white" and "colored" passengers. (To boycott something means to refuse to use or buy it.)

The protesters didn't succeed in changing the law, but they did get a morale boost when big shipping lines took out ads apologizing to black patrons for having to enforce the law.

Mr. Marshall's father, William, was a dining-car waiter for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. His mother, Norma, was a schoolteacher. When he was 2 years old, Mr. Marshall, his parents, and his older brother, William Aubrey, moved to Harlem in New York City. They returned to Baltimore when Mr. Marshall was 6, and he was sent to the elementary school where his mother worked so she could keep an eye on him.

William Marshall had a big influence on his son's choice of a legal career. Speaking of his father, Thurgood Marshall once told a reporter: "He never told me to become a lawyer, but he turned me into one. He did it by teaching me to argue, by challenging my logic on every point, by making me prove every statement I made."

After high school, Mr. Marshall attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the nation's oldest black university. One day he went with some of his college friends to see a cowboy movie in a nearby town. They were forbidden to sit on the main floor of the movie theater and instead were told to move to the "colored" balcony.

Angry at the way they were being treated, the students asked for refunds of the 25 cents they had each paid for their tickets, but the usher refused. "So we had a disturbance ... pulled down curtains, broke the front door," Mr. Marshall's pal Monroe Dowling later recalled, "I don't know who chased us. They didn't catch anybody."

When Mr. Marshall received his college degree in 1930, he wanted to enroll in law school at the University of Maryland. But the all-white school, which had never accepted a black student, rejected his application. He was accepted into the law school at Howard University, a black institution that was founded in 1867 in Washington, D.C., to educate newly freed slaves.

Mr. Marshall graduated first in his class at Howard Law School in 1933. He started his law practice in a small office in Baltimore.

The following year, he began offering legal services to the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The nation's oldest civil rights organization, the NAACP was founded in New York City in 1909.

It was through his association with the NAACP that Mr. Marshall first became involved as a lawyer in the fight against segregation.

By the late 1940s, he had become so famous for his work that some reporters nicknamed him "Mr. Civil Rights." In 1951, he took on a school desegregation case in Clarendon County, S.C. It was the first of the five lawsuits that would eventually become part of the Brown Supreme Court decision.

Oral arguments before the Supreme Court on the Brown case began on Dec. 9, 1952. On May 17, 1954, the court announced its unanimous opinion to a stunned, packed courtroom. Mr. Marshall was right: Legal segregation of public schools was unconstitutional.

When he heard Chief Justice Earl Warren read the court's decision, Mr. Marshall later said: "I was so happy I was numb."

The case marked a major turning point in US history. Largely because of Mr. Marshall's legal victory in the case, laws that discriminated against blacks in housing, employment, and other areas also began to crumble.

In 1961, Mr. Marshall became a federal court judge, and in 1965 he became the first African-American US solicitor general, the lawyer who represents the United States in cases before the Supreme Court.

On Oct. 2, 1967, Mr. Marshall again made history when he took the oath of office to become the first black associate justice of the Supreme Court. African-Americans were very proud of that moment. What an important step it was in the advancement of equality!

Mr. Marshall served on the Supreme Court until his retirement in 1991. After he died on Jan. 24, 1993, Chief Justice William Rehnquist summed up well the impact of Mr. Marshall's life's work. He talked about the words that are inscribed above the front entrance to the Supreme Court building: "Equal justice under law," adding, "Surely no one individual did more to make these words a reality than Thurgood Marshall."