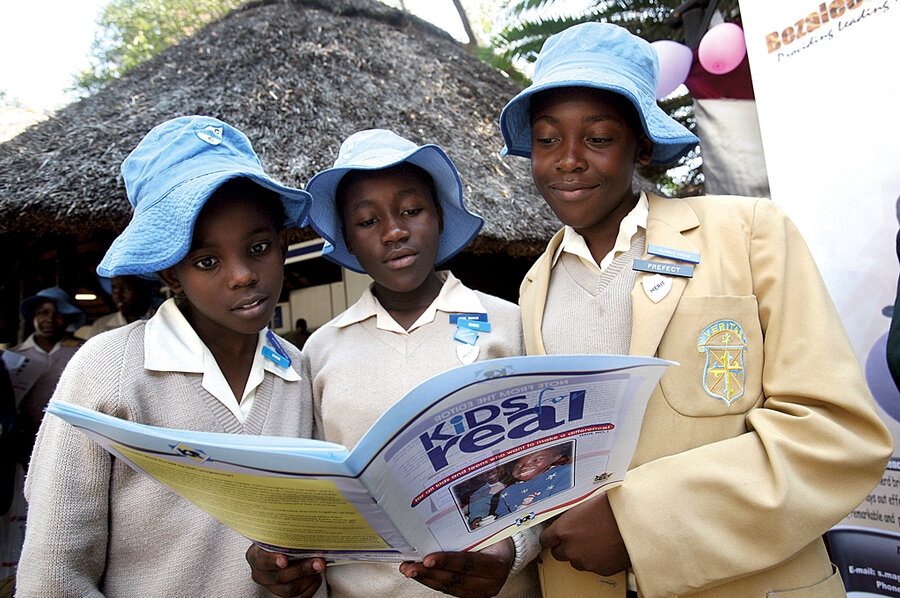

Hungry for books

Loading...

The policeman peered in through the open window of our car. "Can I borrow...?" he began. My heart sank.

This was our sixth police checkpoint in an hour. We were in Marange district, Zimbabwe's eastern diamond heartland. The sand, silhouetted baobabs, and the ever-present security forces made it an eerie place.

Diamonds were first found in the area in 2006, sparking a massive gem rush. Students threw schoolbooks into the bushes in their hurry to dig, their teachers following them in a crazed search for instant riches.

In late 2008, President Robert Mugabe ordered a controversial military clampdown to reassert state control. The authorities have been battling ever since to get the diamonds certified blood-free. Foreigners venturing into the area are viewed with suspicion: They might be diamond buyers or illegal dealers.

With the policeman's eyes upon me, I steeled myself. I knew that like most of Zimbabwe's civil servants, policemen are badly underpaid. (In fact, public service unions are clamoring for a share of the state's diamond wealth to be put into long overdue salary increases.)

"... one of your books?" the policeman finished. He pointed to the dashboard.

My books! I'd almost forgotten them. Before leaving home, I had bundled three paperbacks into the car, hoping to while away a hot journey with a pleasant read.

New and once-read books have reappeared on Zimbabwe's flea markets and in city bookshops since a coalition government was formed between longtime President Mugabe and former opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai in February 2009, putting a tentative stop to 10 years of economic downturn. Perhaps understandably, motivational books now appear to be the biggest sellers.

Not long ago, buying a good book in Zimbabwe was almost impossible. The government booksellers Kingstons sold flags and pens instead, its sparsely stocked shelves mirroring adjacent near-empty supermarkets. Our two favorite secondhand bookstores in Harare closed down, forced out of business by hyperinflation that topped 231 million percent.

Sometimes I felt I was starving for a nice novel. I wasn't the only one. Friends from the ethnic Shona majority begged to borrow magazines or novels sent to me by family members overseas. "Haven't you got anything for me to read?" they'd say. "Give us this day our daily bread" took on a whole new meaning: I realized that Zimbabweans around me didn't just want food, they also craved new texts to read, digest, and discuss.

State-controlled newspapers were not satisfying enough. The local library offered little help. It was "seasonal," I was informed: Because of a leaky tin roof, the library closed during the rainy months. Unfortunately, the authorities had discovered the leaks too late, meaning that many of the books were destroyed.

A habitual flick-reader, I have learned the pleasures of rereading, savoring over and over again sentences I might once have skimmed. I found echoes of Zimbabwe's shortages in British novelist Helen Dunmore's "The Siege," an imaginative reconstruction of the blockade of Leningrad in 1941. I recognized protagonist Anna's joy when she unexpectedly found an onion for her starving family: While we were never that hungry, I, too, had felt a sudden surge of elation when fruit disappeared from the shops but a neighbor invited us to pick mulberries from her tree.

When flour was hard to find, I was soothed by "Miriam's Kitchen," Elizabeth Ehrlich's account of her attempts to integrate her Jewish heritage into daily life. Ms. Ehrlich's meticulous recording of the way to make her Polish mother-in-law's apple cake reminded me that hardships teach us to cherish simple things.

But here on a road in Marange, a policeman was waiting. I looked at the three books on my dashboard. Each one was precious to me: Each had a story. Naomi Alderman's prize-winning novel "Disobedience" I had snapped up with glee when I saw it at a Harare flea market a few days earlier. I bought "The Vintage Book of Cats" soon after we acquired our first feline in 2002. As the tribe expanded, I enjoyed reading extracts from this anthology of cat literature to my husband by candlelight (frequent power cuts have taught us you need a minimum of four candles to read by). My son's former teacher gave us "The Fox Gate," a lyrical collection of stories by children's author William Mayne. Sam and I had just read the tale of a mouse who found his way to Bethlehem.

I looked again at the young officer. Behind him, wet laundry hung on the ropes of a police tent. With Zimbabwe's economy far from flourishing, graduates are joining the force in droves. There are few other jobs available.

"I just want one," the policeman pleaded. I heard the echoes of my own book hunger and knew there was only one thing to do.