Ellipses that drive us dotty

Loading...

They’re enough to make a grown publisher cry: those little dots that indicate material omitted from quoted text.

They’re called ellipses. In an editorial meeting recently, I was asked to review the rules that govern them to recommend a style for our new project.

Curling up with Big Orange back in my office, I was reminded that the Chicago Manual of Style offers no fewer than three sets of rules for ellipses.

The first and simplest is “the three-dot method,” appropriate “for most general works and many scholarly ones.” It uses (surprise!) three dots to mark omissions, whether of an entire sentence or just some material within. “For fidelity to the original and ease of reading,” Chicago notes, a question mark or other punctuation may be tucked in as well.

Chicago doesn’t mention this, but the three-dot method is also sometimes used by writers ... here and there ... who intend to indicate meaningful ... pauses. They tend, though, to suggest instead a stream of consciousness that suffers occasional dry spells.

The “three-or-four-dot method,” which Chicago calls “appropriate for poetry and most scholarly works other than legal writings or textual commentary,” involves three dots for omissions within a sentence and four for omissions of whole sentences.

Finally, there is the “rigorous method,” a sort of “three-or-four-dots plus.” It includes, among other things, additional fastidiousness about capitalization – any change from the original printed source must be noted with brackets. Chicago’s discussion of “the rigorous method” also includes, in my edition, three paragraphs on “Placement of first dot.” The rigorous method is clearly not for the faint of heart.

I can see I have some noodling to do before I get back to my client on this one.

Meanwhile, inquiring minds want to know, what’s the connection between ellipsis and ellipse?

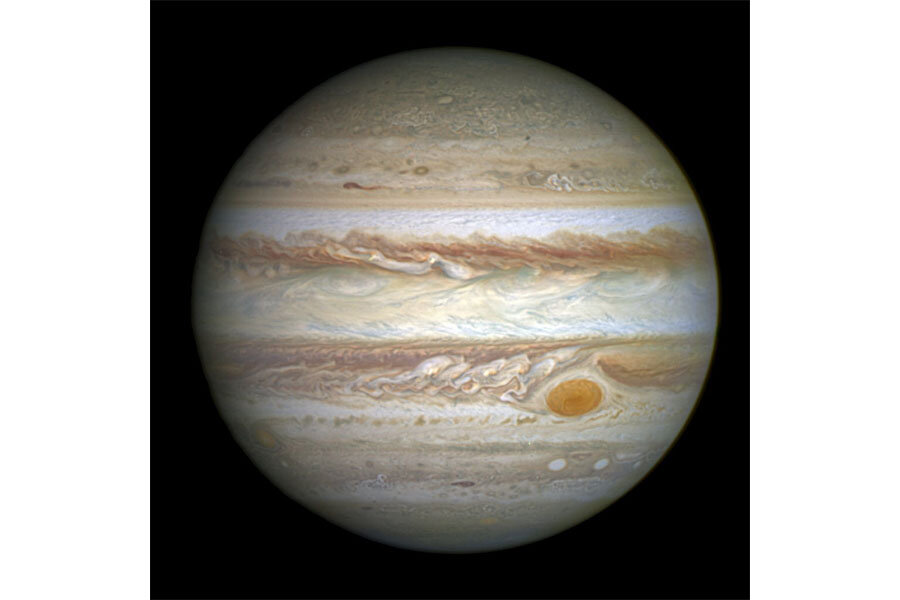

The common ancestor for the words for both the editor’s little string of dots and the geometer’s almost-circle – the shape of the orbits of planets – turns out to be the Greek verb elleipein, meaning “to fall short or leave out.” The related noun means “a deficit.”

In geometry, an ellipse is “a shape similar to a circle but longer than it is wide.” That’s Macmillan’s quick online definition, anyway.

Perhaps it was written by an English major and not a mathematician? Another way to put it would be to say an ellipse is like a circle but with two “centers” rather than one.

But why the deficit metaphor? Ellipses are seen as sections (slices) of cones, and they got their name, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “because the conic section of the cutting plane makes a smaller angle with the base than does the side of the cone, hence, a ‘falling short.’ ”

My etymological curiosity now satisfied, I’ll return to figuring out how to deal with all those dots. Chicago certainly doesn’t fall short on options.