Eleven portraits of those who died on the Deepwater Horizon

Loading...

Jason Anderson, 35, Midfield, Texas.

Jason Anderson wasn't even supposed to be on the Deepwater Horizon that day. Anderson had been with the rig since it launched from a South Korean shipyard in 2001. By 2010, the Bay City, Texas, man had risen to senior tool pusher, akin to a foreman on a construction site.

Anderson was transferring to another rig, and went out to the Deepwater Horizon to train his replacement, says his widow, Shelley. When he arrived, the trainee wasn't there, but Jason stayed over to clean out his locker and spend just a little more time with his "rig brothers."

___

Aaron Dale Burkeen, 37, Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Known to friends and family as "Big D" or simple "Bubba," Burkeen's favorite television show was "Man vs. Wild," about people dropped into the wilderness. He once told his sister: "Anything ever happens to me on that rig, I will make it. I'll float to an island somewhere. Y'all don't give up on me, 'cuz I will make it."

Burkeen was a crane operator on the Deepwater Horizon and had worked for Transocean for a decade before the disaster. Survivors said the blast blew him off a catwalk, and that he fell more than 50 feet to the deck.

He left behind a wife, Rhonda, and two children.

___

Donald "Duck" Clark, 49, of Newellton, Louisiana.

Sheila Clark says her late husband liked his job as an assistant driller on the Deepwater Horizon. But the avid fisherman and family man "never really enjoyed leaving home."

"He left that job out there, he really did," says his widow, who was in her mid-20s when relatives introduced her to Clark when he moved back to Newellton. "If I would ask him about it, he would express (that) he didn't want to talk about it. 'Don't worry about it. I don't want to talk about it.'"

They were married for 20 years and had four children. Unlike most of the other families, Sheila Clark chose not to have an empty grave for Donald.

"I don't need objects to remind me of him," she says. "I have my children ..."

___

Stephen Ray Curtis, 40, Georgetown, Louisiana.

An assistant driller on the Deepwater Horizon, Curtis followed in The footsteps of his father, who was a diver-welder. At the time of his death, the son had been in the oil industry 17 years.

The Marine veteran was a member of the Georgetown Volunteer Fire Department and had also served as an officer with the Grant Parish police department. Curtis was a fan of NASCAR, especially driver Jimmy Johnson, and loved baseball and bow hunting for deer and turkey — passions he tried to share with his son, Treavor.

Curtis' co-workers said his turkey call was so realistic, they half expected one of the birds to land on the rig.

He left behind a wife, Nancy, son and a daughter, Kala, who had given him his first grandchild shortly before the explosion. For his memorial service at Georgetown Baptist Church, the family asked that everyone wear camouflage in his honor.

___

Gordon Jones, 28, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

A drilling fluids specialist for M-I SWACO, the Louisiana State University graduate had hung up after talking with his wife, Michelle, just 10 minutes before the rig exploded. It was three days shy of their sixth wedding anniversary.

Two months after Jones' death, his widow gave birth to their second son — Maxwell Gordon, a name they'd decided on shortly before he left on his last hitch.

Michelle has remarried. But the family works hard to make sure Stafford, 7, and Max know who their father was.

___

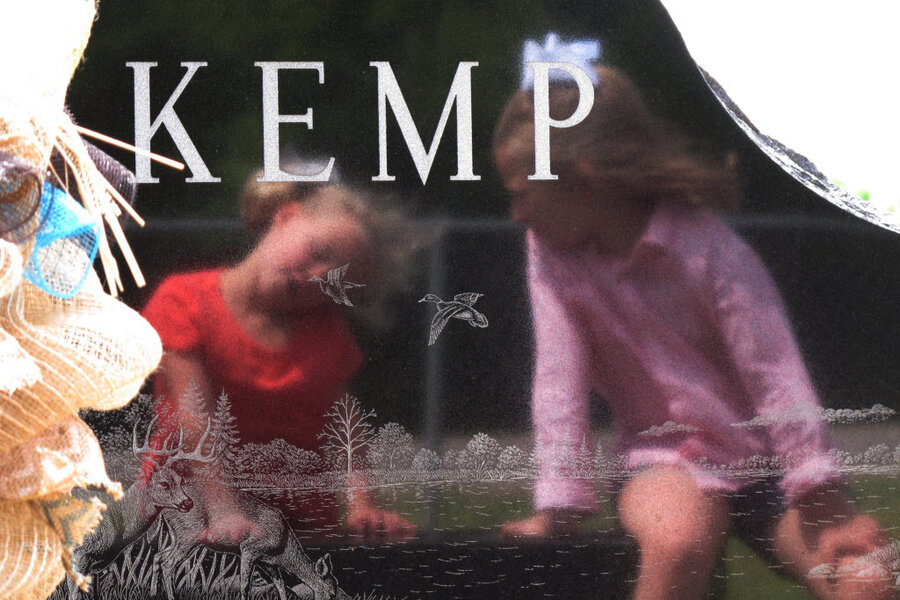

Roy Wyatt Kemp, 27, Jonesville, Louisiana.

Baptized in a Colorado creek during a youth trip, faith was central to Wyatt Kemp's life. Out in the Gulf, he would listen to sermons that a friend had loaded onto his MP3 player.

In the weeks leading up to the disaster, Kemp hinted to his wife, Courtney, that there were problems on the rig. He started planning his funeral, asking his wife to bury him with photos of their two girls, Kaylee and Maddison.

With no casket to put them in, his widow had the pictures laser-etched onto his gravestone.

___

Karl Kleppinger Jr., 38, Natchez, Mississippi.

The Baton Rouge native served in the Army during Operation Desert Storm and had worked for Transocean for 10 years. He was a floor hand at the time of the disaster.

The beefy, red-bearded Kleppinger was a NASCAR fan and loved cooking barbecue. He and his wife, Tracy, adopted a number of animals from the Natchez Humane Society, and the family asked that donations be made to that organization in his honor.

Kleppinger left behind a son, Aaron. His widow has remarried.

___

Keith Blair Manuel, 56, Gonzalez, Louisiana.

Known on the rigs as Papa Bear, Manuel's hunting buddies called him "Gros Bebe" — or "big baby." A senior drilling fluids specialist, the goateed Manuel worked for Houston-based M-I SWACO, which supplied materials to the Deepwater Horizon. The father of three grown daughters was planning to marry his fiance when he was killed.

Because there was no body, the family buried a memory box beneath His stone at Mount Calvary Cemetery in Eunice, Louisiana.

___

Dewey Revette, 48, of State Line, Mississippi.

Revette had been a driller with Transocean for 29 years. He was the chief driller on April 20, 2010, and was reportedly arguing with one of the BP supervisors now facing manslaughter charges in the disaster.

A "nut for Jeeps," according to The New York Times, Revette left behind his wife of 26 years, Sherri, and two adult daughters. Two grandsons born since the disaster are named for him.

___

Shane Roshto, 22, Liberty, Mississippi.

Roshto was studying to be a medical radiologist. But when his girlfriend, Natalie, told him she was pregnant, he quit school, applied to go offshore and landed an ordinary seaman's position on the Deepwater Horizon.

Over the next four years, Roshto would work his way up the ladder to lead roughneck. But he never forgot the real reasons he was out there.

Embedded in his wedding band was a strand of steel cable, the same kind used on the rigs. Written in Wite-Out under the brim of his blue hard hat were two dates: His and Natalie's anniversary, and their son Blaine's birthday.

"If he had a hard day, he could take that hardhat off and he could look at those two dates," says his widow, who has since remarried. "And it would always get him through the rest of that day."

___

Adam Weise, 24, Yorktown, Texas.

Weise was so proud of the little house he'd bought in Yorktown, Texas, that he didn't mind the 10-hour drive every three weeks to get back to work on the rig. His other prize possession: A black, four-wheel-drive diesel pickup truck he'd dubbed "The Big Nasty."

"It was every boy's dream," says his mother, Arleen. "It's the kind of truck he always wanted, and he got it."

Growing up without a father, Weise learned to hunt and fish from his grandfather. The youngest of four children, Weise was a star player for the Yorktown High School football team, known as a member of the Wildcats' "fabulous five."

He went offshore not long after graduation in 2005 and was a floor hand aboard the Deepwater Horizon at the time of the disaster.