Save Our Schools March: a teacher revolt against Obama education reform

Loading...

What if the education reformers are wrong?

That's the opinion of a growing number of educators who are convinced that the current direction of reform – despite powerful backers that include President Obama, Bill Gates, and many influential academics and nonprofit leaders – is harming public schools rather than improving them.

While teachers unions and a number of prominent education thinkers have been critical of the reform policies for some time, a more concerted effort is emerging to organize those critics. They plan to take to the streets in Washington on Saturday in hopes of galvanizing attention around their cause. The Save Our Schools March has attracted endorsements from well-known academics, educators, and authors.

Passionate and articulate, many of them classroom teachers, the critics tend to zero in on the increasingly high-stakes role played by standardized tests, which can make or break the reputation of a school or teacher – even if the tests aren't very good.

"What we call 'accountability' now is just totally unreliable numbers that are meaningless in terms of the lives of children and the careers of teachers," says Diane Ravitch, a historian and former advocate of standards-based reforms who is now one of its most frequent and ardent critics. "All they're doing is terrorizing teachers."

Attaching so much importance to tests, say such critics, is leading to unintended consequences – including cheating (with the recent scandal in Atlanta as Exhibit A), a narrowing of the curriculum, and the reduction of many schools into test-prep factories that ignore the higher-thinking skills needed for college and the workplace. Instead, they assert, more attention should be paid to poverty and the related factors affecting students' achievement, teachers should get better support and training, and evaluations should be more nuanced.

Although the Obama administration has been trying to address what it sees as shortcomings in the No Child Left Behind law, critics say that overall the administration is going in the wrong direction on reforms.

"This is impassioned educators pushing back for good or bad," says Frederick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington, who is generally an advocate of standards-based reforms. "I think it's clear that this isn't union power tactics."

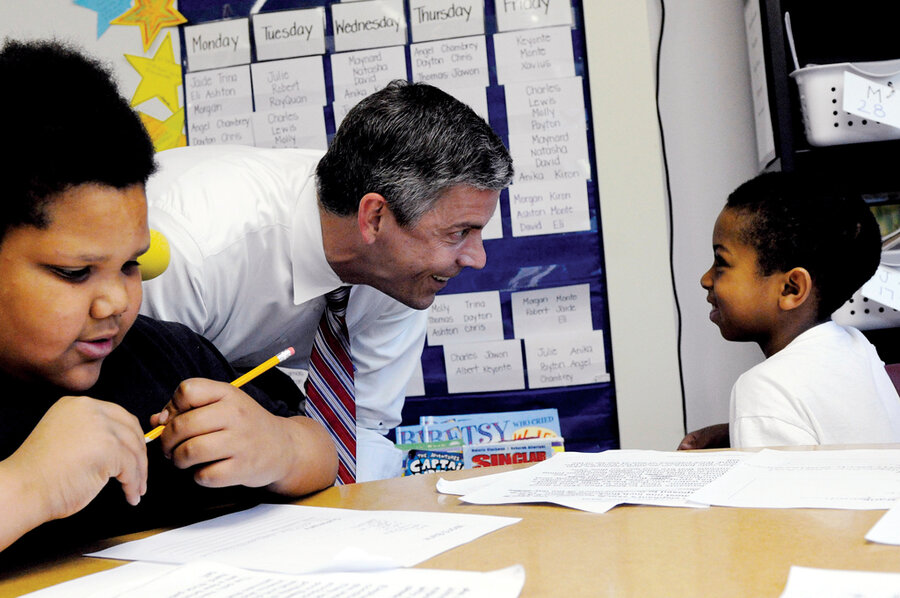

In May, US Education Secretary Arne Duncan wrote an open letter to America's teachers for Teacher Appreciation Week acknowledging many of the concerns voiced by teachers. He concluded the letter, "I hear you, I value you, and I respect you."

Rather than appeasing teachers, it unleashed a storm of angry blogs, letters, and comments from educators who feel far from appreciated.

"The things you say here are, as Hamlet once said, 'words, words, words,' but there is no substance behind them," reads a typical comment about the letter, posted on the Department of Education's website. The teacher also says, "The education policies of this administration are the single reason why I will not vote to reelect Barack Obama in 2012."

Why such disgruntlement?

Certainly, some teachers are unhappy for professional reasons, seeing everything from their pay to, in some cases, their job security hinging on tests they don't believe in. Others rail against the constriction of their autonomy in the classroom.

Sabrina Stevens Shupe, an organizer of the march and a former teacher in the Denver Public Schools, recalls her frustration with a district that hired her for her creativity and praised her for the strides she was making on math with her fifth-graders, but then criticized her for not following the prescribed curriculum exactly – even when she had seen it wasn't working.

"I was handed a book and was supposed to read verbatim each section," she recalls, with a district "support" person there to monitor her compliance. For reading, she was supposed to pair students up and have them read to each other, counting each other's words and mistakes – although in many cases, neither child understood what he or she was reading. "Comprehension didn't enter into it," she says.

Ms. Shupe's contract wasn't renewed at the end of the year despite only positive evaluations. Now, as a blogger and activist, she says she hears dozens of stories similar to hers.

"We need to be creating conditions that inspire people to do their best work, instead of punishment and reward systems that inspire lowbrow work and cheating," she says.

Still, despite the angry rhetoric heard on both sides, many leaders of the standards-based reforms insist there is more agreement than people realize.

"We all want the best for kids, and we all want more students, regardless of their circumstances, to graduate high school ready for postsecondary education. There is a very legitimate debate about how best to get there," says Jonah Edelman, cofounder and chief executive officer of Stand for Children, an advocacy group that has pushed for laws in many states that, among other things, hold teachers more accountable and make job security more dependent on performance.

Like many leaders identified with the accountability movement, Mr. Edelman emphasizes that the goal has never been just about test scores, but about how to get students learning. He bemoans any policy that encourages teachers to teach to a poor test or to cheat. But without some form of measurement, too many students will fall through the cracks, he worries.

"The answer lies in striking the right balance between effective assessment of and for learning, and accountability that is smart," Edelman says. "It's a little bit of a zigzag, but overall we're moving in the right direction."

Many of the reform movement's biggest critics are quick to say that it's not that they disagree with assessments; it's the top-down, high-stakes nature of the tests that they have a problem with as well as the minimal effort to get buy-in from teachers and parents for the policies.

Recently, the National Education Association approved, for the first time, a policy that student achievement should be a factor in teacher evaluation. But it simultaneously asserted that no system currently does so in the right way.

Anthony Cody, a longtime teacher and teacher coach in Oakland, Calif., and another organizer of the march, says he's seen many mediocre teachers get excellent test scores for kids and outstanding teachers get worse ones.

He remembers students complaining when a group of teachers was giving them challenging writing and thinking projects. The students asked them why they didn't just do what the prior year's teacher had done and say what would be on the test.

"We have managed to transmit from the highest level in the nation to these individual students in Oakland that what matters is the test score," says Mr. Cody. "These students are going to get to college and find their professors don't actually say, 'Here are the 50 questions that will be on the test.' "

A common refrain among disgruntled teachers is that the current policies aren't leading to the kind of schools that the top leaders would want to send their own children to. The Obamas, for instance, send their daughters to the private, progressive Sidwell Friends School – not a place known for test prep or a narrow curriculum.

So where will the backlash against the reforms lead?

It's unlikely that the policies of accountability and testing are going to be stopped, given their momentum. But even some advocates of those policies say that more debate may ultimately be a good thing for education.

"There is a simple-mindedness, an arrogance, and a reflexiveness with which the reformers are pushing their agenda, particularly from Washington, and I think they've wound up giving classroom educators serious and fair cause for concern about how things like value-added evaluations or merit pay are taking shape," says Mr. Hess of AEI. "This pushback both helps call attention to the need to do this smarter and offers an opportunity to slow down and pursue these things with the deliberation and thoughtfulness they require."