Denver teachers strike for higher wages, exposing US divide over bonus pay

Loading...

| Denver

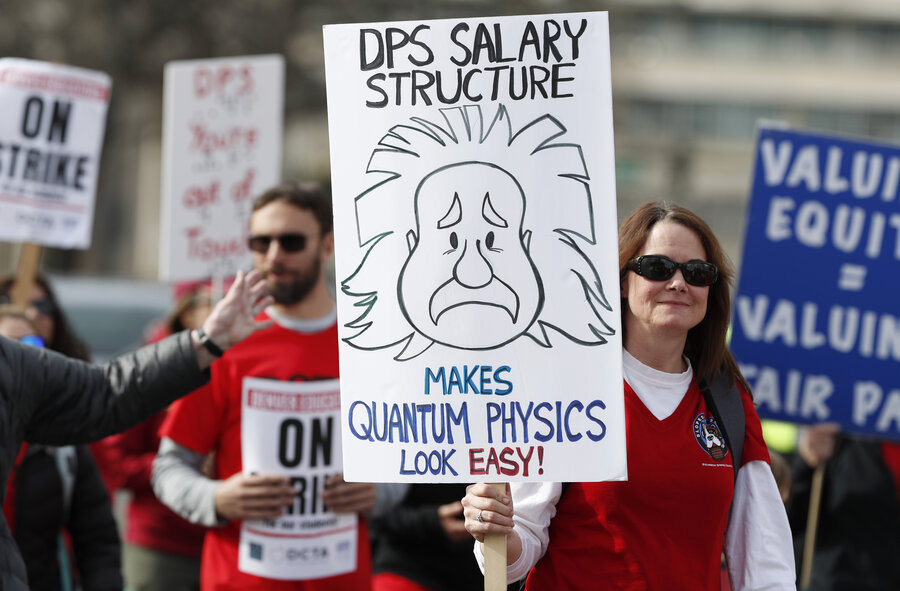

Denver teachers went on strike to improve their pay, but the fight wasn't that simple.

Emboldened by teacher activism nationwide and struggling to live in a rapidly growing city, Denver educators are challenging one of the nation's oldest incentive pay systems, which is endorsed by the teachers union and education reform advocates and funded by a voter-passed property tax increase in 2005.

The system known as Professional Compensation, or ProComp, allows teachers to add on to their base salary by earning bonuses of up to $3,000 a year for working in a hard-to-staff position or high poverty school or if their schools improve.

But teachers say the system is complicated and can leave them guessing at what their earnings will be.

Sarah Olsen, a third-grade teacher at Maxwell Elementary School, said she was already living on a tight budget when she lost a chunk of her paycheck. The number of students getting free and reduced-price lunch – a measure of poverty – dipped below the threshold for getting an incentive for a school ranked as "hard to serve."

Ms. Olson also said the district cut the promised bonus to teachers at the school for improved test scores.

"There's just no consistency with the incentives," she said. "They can be taken away at any time. They can be reduced."

With the use of incentive pay rising among districts and states, here's a look at the discussion:

Is incentive pay widely used?

"We've seen a tremendous increase in the number of schools, districts and states that are experimenting with incentive pay programs across the country," said researcher Matthew Springer, who has studied the widely varying programs for 20 years.

Mr. Springer, distinguished professor of education reform at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said an influx of federal funds through programs like Race to the Top and the Teacher Incentive Fund have encouraged more states to explore the idea.

Most states now allow for some sort of incentive pay, whether it's offering bonuses to teach in high-needs schools or subjects or basing raises on student or teacher performance.

Nine states require districts to consider performance in teacher pay and at least 11 states allow it, according to the nonprofit National Council on Teacher Quality, a research and policy organization. A majority of states incentivize pay for high-needs schools and subjects.

What do teachers dislike about it?

Market-driven recruiting and retention bonuses are generally accepted, but bonuses linked to student and teacher performance are more controversial. Teachers say it's not fair to pay them based on standardized test scores that are affected by factors beyond their control, like poverty.

Teachers also say they are self-motivated and not driven by bonuses the way a salesperson may be, for example. Many would rather see funding used to increase the base pay of all teachers, not awarded in a way that can create friction and competition within a school.

"Performance pay has become just another way of nickel-and-diming educators because erratic bonuses are no substitute for sustainable living wages, especially as costs keep rising," American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten said. "This just injects more instability into a profession that's becoming ever more precarious."

In Denver, the main sticking point over bonuses is how much extra to pay teachers who work in high-poverty schools and in one of 30 struggling schools. The district sees those bonuses as key to helping improve the academic performance of low-income students. It says it also needs to honor the will of voters to spend tax revenue worth about $33 million a year on incentive pay.

"There is not one school district in the country that is going to look at Denver and think, 'Oh, I think I'll try that,' " National Education Association President Lily Eskelsen García said after joining picketing Denver teachers this week.

Then why use it?

There are a lot of reasons for incentive systems, Springer said, including the idea that teachers should be compensated for results in the classroom, not just years of service.

"One of the things that I think is important about these systems, particularly well-designed ones, is it's getting us to a point where we can pay our highest-performing educators a six-figure salary," Springer said. "And I think our best and brightest educators deserve a six-figure salary. But unfortunately, the single salary schedule is never going to let us get there."

An incentive pay program also may be less expensive than a general pay raise and an easier sell for districts in need of taxpayer support, he said.

Do bonuses for teachers help students?

A 2017 analysis of more than 30 studies on merit pay found that it has a modest positive effect on student test scores. The academic gains were roughly equivalent to adding three weeks of learning to the school year, said Springer, who co-led the study while a professor at Vanderbilt University.

An unpublished University of Colorado study of ProComp that compared test scores in Denver with those of nearby districts between 2001 and 2016 found the bonuses may have helped increase student achievement.

The study by assistant professor Allison Atteberry, which is being peer-reviewed, also found that the district retained teachers at higher rates who were rated as more effective based on their students' test score growth than those ranked as less effective since the incentive system began.

The study did not find evidence that the bonuses caused teachers to transfer into high-poverty or top-performing schools. But there was some indication that the rate of teachers leaving hard-to-serve schools slowed.

Where else is this being discussed?

Florida's teachers union contended in a 2017 lawsuit that the state's bonus program is discriminatory. It relies in part on college entry exam scores. Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) this month proposed reforming the program, and no longer tying it to exams. He said nearly 45,000 highly effective teachers would be eligible for bonuses exceeding $9,000.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) won applause in his State of the State address when he raised the idea of rewarding successful teachers with incentives that could help them earn a six-figure salary. But union leaders said the state test shouldn't be the measure of teacher success.

"The governor gives offense to Texas teachers every time he and his education commissioner claim to want more pay for the so-called best teachers," Louis Malfaro, president of the Texas AFT union, said in a statement. "The implication being that the hundreds of thousands of women and men who teach and support the 5.4 million students in Texas' public schools are unworthy of being paid decently for the hard work they do every day."

This story was reported by The Associated Press with Carolyn Thompson reporting from Buffalo, N.Y.