As Texas execution looms, defense says state withheld low IQ scores

Loading...

Lawyers for a Texas man scheduled to be put to death Tuesday are asking for a stay of execution over multiple questions about the state’s secrecy in planning the execution, including allegations that it withheld the condemned man’s lowest IQ test results.

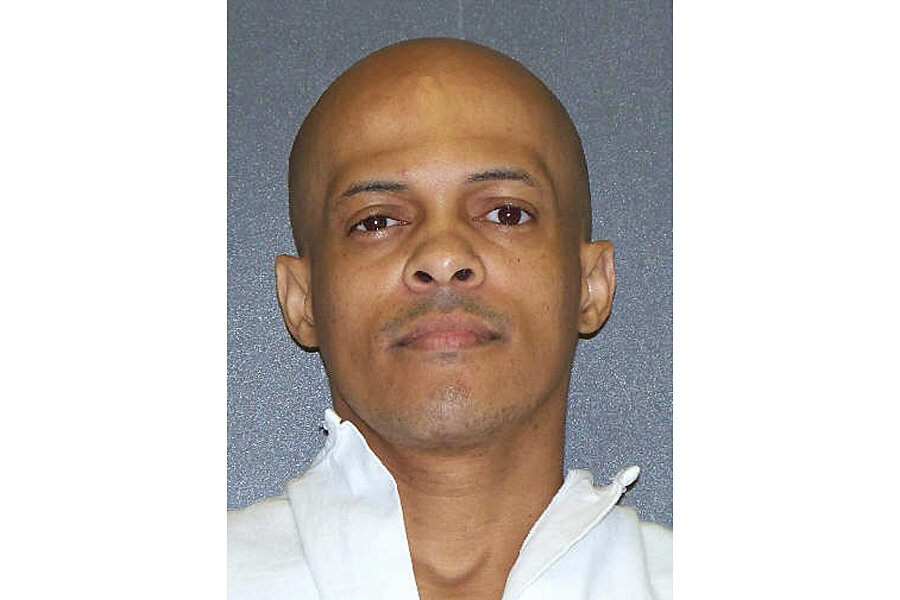

Robert Campbell, who is scheduled for execution at 7 p.m. EDT, would be the first inmate to be put to death in the United States since Oklahoma’s botched execution of Clayton Lockett April 29. Oklahoma last week put off all executions in the state for at least six months, and President Obama has called on the US Justice Department to begin reviewing how the death penalty is practiced.

Lawyers for Mr. Campbell have said the state is violating the inmate’s constitutional right not to face cruel and unusual punishment by withholding both the source of its lethal injection drugs, and until recently, the condemned man’s low IQ scores. A 2002 Supreme Court ruling bars the mentally handicapped from execution, on the grounds that the Eighth Amendment protects from execution people unable to understand the punishment.

“They [Texas] didn’t reveal some of the IQ scores, and they didn’t reveal the source,” says Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. “This is someone’s life. This is the time you want to put all the information on the table and let the judges and the juries decide.”

“The whole world will be watching this execution, and there’s all the more reason that the state will want to do everything it can to make sure it gets it right,” he says. “I’m not sure it has done that yet.”

At issue in one of Campbell’s appeals, which was sent to the US Supreme Court Tuesday afternoon after being turned down by multiple lower courts, is that Texas, like Oklahoma, sources its drugs from a pharmacy it refuses to name. Though Texas uses a single-drug lethal injection method, which experts have cited as preferable to Oklahoma’s three-drug process, Campbell’s lawyers have argued that the condemned man has a right to know if the drugs the state plans to use on him are clean and effective.

Lawyers for Campbell also say that the bungled execution in Oklahoma, in which it took 43 minutes for Mr. Lockett to die, is evidence that no state (including Texas, which leads the US in executions) can guarantee that lethal injections will go as planned.

“The American public is losing confidence in the state’s ability to do this right,” says Diann Rust-Tierney, the executive director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, in Washington, D.C. “The whole system is out of control.”

In a separate line of argument, Campbell’s lawyers are also asking the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles to commute Campbell’s death sentence to life without parole, based on their allegation that the Texas Department of Justice withheld IQ scores supporting Campbell’s claim that he is mentally handicapped. On Tuesday, Campbell’s legal team asked Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) to grant a 30-day stay of execution, to give the board time to consider Campbell’s application.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals voted 5 to 4 last week to dismiss the argument that Campbell is mentally unfit, but did so on procedural grounds, saying it had already ruled on the matter in 2003.

But the four dissenting judges, in a 6-page opinion, argued that the court had erred in refusing to consider considerable new evidence about Campbell’s mental status. According to the opinion, the court’s decision in 2003 was based on just one IQ test administered by the prison system in 1990, in which Campbell scored 84. The median IQ is 100.

At the time, the prison system told Campbell’s then-lawyers that no other IQ test existed, according to a statement provided by Rob Owen, one of Campbell’s current lawyers. But, within the last few weeks, Campbell’s current legal team uncovered a second test from 1992, which put his IQ at just 71. His lawyers said they also discovered that the District Attorney’s Office in Houston had school records putting Campbell’s IQ at 68, but had not turned those over to the defense, according to Mr. Owen’s statement.

Had the Texas Department of Justice “not misinformed ... regarding applicant’s available IQ scores, then this court would have had IQ testing supportive of applicant’s mental-retardation claim,” wrote Judge Elsa Alcala, in the dissenting opinion.

Campbell was sentenced to death for killing Alexandra Rendon, a 20-year-old bank teller whom he abducted from a gas station, drove to a secluded area, raped, and told to “run” before shooting her in the back and leaving her to die.

The US Supreme Court is preparing to rule on a separate case regarding a condemned Florida man whose lawyers say he is mentally handicapped. Though the Court’s 2002 ruling exempts the mentally disabled from execution, it also allows states to set their own standards for intellectual disabilities. At issue before the Court, which is expected to rule before the end of June, is that Florida considers a score above 70 to be a strict bright line for the death sentence, even though the IQ test makers say a five-point margin of error should be applied to all scores.

Texas, though, does not have a law setting a minimum IQ standard, and judges instead follow legal precedent that allows the court to weigh various factors in determining eligibility for the death sentence.

That flexibility has produced its own set of questions, since it allowed the state in August 2012 to execute Marvin Wilson, who had at least one IQ score as low as 61.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals wrote that Lennie, the mentally disabled character from John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” was its standard for who should not be executed. Death penalty opponents, as well as Mr. Steinbeck’s grandson, responded with outrage that a fictional character had been used as a barometer of intellect in a life-or-death decision.