How James Holmes life in prison jury decision reflects death penalty trends

Loading...

The jury’s penalty decision in the case of Colorado theater shooter James Eagan Holmes – life in prison without parole instead of execution – reflects the nation’s attitude about such cases tied to mental illness.

While most Americans still favor the death penalty (63-33 percent for those convicted of murder, according to the most recent Gallup survey), a clear majority oppose the ultimate punishment for those diagnosed with severe mental illness amounting to insanity – 58-28 percent, a Public Policy Polling (PPP) survey showed last December.

That opposition is consistent across party affiliations: 62 percent of Democrats, 59 percent of Republicans, and 51 percent of Independents all agree that mentally ill persons should not be executed. Similar majorities were found across both genders, as well as economic and education levels.

“The poll joins other new data demonstrating that sentencing trends are down across the country for death-eligible defendants with severe mental illness,” said University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill law professor Robert Smith, who commissioned the survey.

“Combining this public polling, sentencing practices, and the recommendations of the mental health medical community, it’s clear that a consensus is emerging against the execution of a person … who suffers from a debilitating illness which is similar to intellectual disability in that it lessens both his culpability and arguable social value of his execution,” said professor Smith in releasing the survey.

The extent to which Holmes fit that degree of incompetence to tell right from wrong was the nub of his trial.

There was no denying that he had carefully planned and carried out one of the most heinous mass killings in US history.

On July 20, 2012, he entered a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, for the midnight premiere of “The Dark Knight Rises,” the latest Batman sequel, propped open an exit door, then later returned through that door dressed in military protective gear and armed with a military-style semiautomatic rifle, a shot gun, a pistol, and extra ammunition.

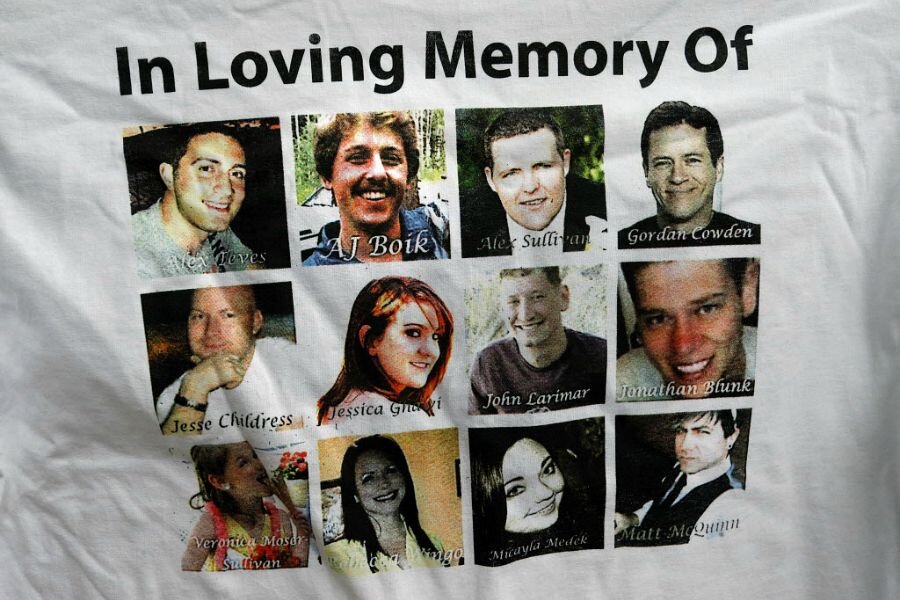

After setting off a smoke grenade, Holmes began firing at moviegoers, killing 12 and wounding 70. He was arrested just outside the theater, having offered no resistance. Police later found his apartment rigged with explosives.

The horrific aftermath of the attack, videotaped by police, was played and replayed for jurors.

Holmes psychiatric history – including suicide attempts and depression over his failure as a graduate student – featured prominently in the defense’s presentation.

Raquel Gur, director of the Schizophrenia Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, spent four days on the stand defending her opinion that Holmes was legally insane when he committed the crime.

"He was not capable of differentiating between right and wrong," Dr. Gur said. "He was not capable of understanding that the people that he was going to kill wanted to live."

Two court appointed psychiatrists concluded that Holmes was sane when he committed the crime, but they also acknowledged that he was severely mentally ill.

"The evidence is clear, that he could not control his thoughts, that he could not control his actions, and he could not control his perceptions," defense attorney Daniel King said during closing arguments. "Only the mental illness caused this to happen and nothing else.”

Prosecutors urged jurors to reject that contention.

"Look at the evidence then hold this man accountable," Arapahoe County District Attorney George Brauchler said in his remarks. "Reject this claim that he didn't know right from wrong when he murdered those people and tried to kill the others…. That guy was sane beyond a reasonable doubt, and he needs to be held accountable for what he did."

The jury of nine women and three men, which had found Holmes guilty on twenty-four counts of first-degree murder and 140 counts of attempted first-degree murder, took about seven hours to reach a decision on the penalty phase of the trial – an outcome that obviously illustrated the very difficult legal (and human) situation they had agreed to be part of, especially since it involved differing assertions as well as professional diagnoses of the defendant’s mental health.

Outside the courthouse in Centennial, Colo., an unidentified juror told reporters that a single juror had held out in opposition to the death penalty and two others were wavering in their support for executing Holmes. It would have taken a unanimous decision to order an execution.

Public support for the death penalty has varied over the years, dropping to a low of 42 percent in 1966 and climbing to a high of 80 percent in 1994, according to Gallup. But it has continued to gradually drop over the past 20 years, although it still stands at 63 percent for convicted murders. Since the attacks of 9/11, the figure has remained high for terrorists who kill people.

But public attitudes and state policies have been shifting in significant ways regarding the death penalty – some of that because of personal beliefs about what critics see as revenge killing by the state, but also because of legal issues and logistical difficulties, including botched executions involving drugs exceedingly difficult to obtain and the continuing string of cases in which individuals long-imprisoned have been found to be innocent.

When poll respondents are given the choice of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole the number favoring the death penalty drops significantly – to 50-45 percent approval.

A Pew Research Center poll, taken six months after Gallup’s most recent survey, found a narrower split between death penalty supporters and opponents (56-38 percent). “Support for the death penalty is as low as it has been in the past 40 years,” Pew reported in April.

Pew also found 71 percent saying there is some risk that an innocent person will be put to death, 61 percent agreeing that the death penalty does not deter people from committing serious crimes, and about half (52 percent) saying that minorities are more likely than whites to be sentenced to death for similar crimes.

Earlier this year, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf (D) suspended the death penalty, saying in a statement: “If the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is going to take the irrevocable step of executing a human being, its capital sentencing system must be infallible. Pennsylvania’s system is riddled with flaws, making it error prone, expensive, and anything but infallible.”

The legislature in Nebraska recently voted to replace the death penalty with life without parole. The vote was 30 to 13. Most Republicans (17 out of 30) joined Democrats in approving the bill.

In an interview at Duke Law School recently, US Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg suggested that geography can play a role in whether someone convicted of a capital offense is sent to the death chamber.

“Yes there was racial disparity but even more geographical disparity,” Justice Ginsburg said. “Most states in the union where the death penalty is theoretically on the books don’t have executions."

"Last year, I think 43 of the states of the United States had no executions, only seven did, and the executions that took place tended to be concentrated in certain counties in certain states,” Ginsburg said. “So the idea that luck of the draw, if you happened to commit a crime in one county in Louisiana, the chances that you would get the death penalty are very high. On the other hand, if you commit the same deed in Minnesota, the chances that you would get the death penalty are almost nil.”

It’s impossible to know whether that was a factor in the jury’s decision to send James Holmes to prison for the rest of his life rather than kill him. But according to the Death Penalty Information Center, Colorado has executed only one person since capital punishment was reinstated 40 years ago.