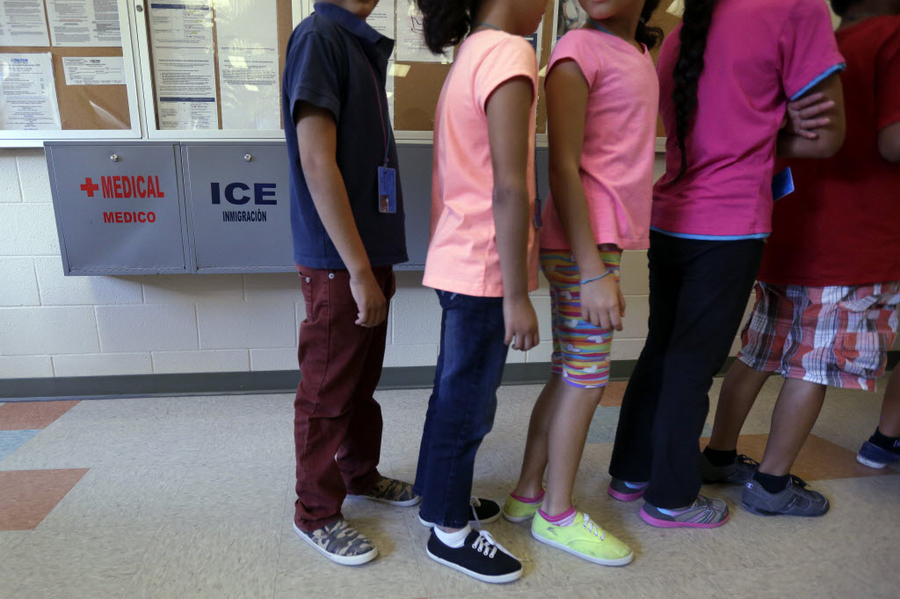

Are child immigrants being held in 'prison facilities'?

Loading...

A Texas detention facility used to hold families caught illegally entering the United States through its southern border received a temporary residential child-care license from state authorities last week.

The Karnes City, Texas, center holds 500 beds for immigrants apprehended in the US, but last year a judge ruled that it would have to refrain from keeping children there as it did not meet licensing requirements.

But even now with the proper authorization there is concern about the conditions, including medical care, at the facility. GEO Group, Inc., a correctional services company based in Florida, runs the detention center for US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. That management decision has some worried about the treatment of immigrants there, and in a similar 2,400-bed facility in Dilley, Texas, around 90 miles away – also run by a private prison company, Corrections Corporation of America.

"Anyone who has been to either of these facilities understands that they are prison facilities," Bob Libal, the executive director of the anti-incarceration organization Grassroots Leadership, told the Associated Press.

"By all reasonable measures, family detention camps are prisons. They are not childcare facilities," Mr. Libal said in a Grassroots release.

Libal's group reported Tuesday that it, along with two immigrant mothers who were detained with their children, had sued to halt the licensing process for the Karnes County Residential Center and South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley.

The move comes after Grassroots successfully stopped the state's Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) from using an emergency rulemaking procedure to issue the licenses. The agency responded by adopting a permanent rule resulting in the licensing grant.

"The real question is, does an agency have the right to license a prison as a child-care facility? We think that the answer is no," Libal told AP.

"Changing an interpretation of Texas law to help federal immigration officials enforce harsh detention policies is disingenuous and detrimental to the health of children in Texas," Libal added in the Grassroots statement.

The focus on detention and care for accompanying children has risen recently amid a spike in captures of unaccompanied children – a 78 percent jump from October through March – and a doubling in the apprehension of families.

Inspections of the Karnes City and Dilley revealed several deficiencies, although DFPS spokesman Patrick Crimmins said they had been corrected and would be backed up by irregular inspections during the duration of the temporary license. Issues included leaving children in their rooms alone and finding an employee was not qualified to work there.

In Dilley, safety problems comprised of hazards such as the presence of medical supplies including used syringes on facility countertops and exposed seams on the center’s playground. The South Texas Family Residential Center will not be issued its temporary license until those issues are solved.

Material from The Associated Press was used in this report.