Federal court finds pay differences based on prior salaries discriminatory

Loading...

| San Francisco

Relying on a woman's previous salary to determine her pay for a new job perpetuates disparities in the wages of men and women and is illegal when it results in higher pay for men, a federal appeals court ruled Monday.

The unanimous ruling by an 11-judge panel of the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals came in a lawsuit filed by a California school employee who learned over lunch with colleagues in 2012 that she made thousands of dollars less than her male counterparts.

The Ninth Circuit held that pay differences based on prior salaries are inherently discriminatory under the federal Equal Pay Act because the previous salaries were the result of gender bias.

"Women are told they are not worth as much as men," Judge Stephen Reinhardt wrote before he died last month. "Allowing prior salary to justify a wage differential perpetuates this message, entrenching in salary systems an obvious means of discrimination."

Debra Katz, an employment attorney in Washington, who handles equal pay lawsuits, said the ruling undercut one of the key arguments that employers have made for allowing pay disparities to continue.

"Employers always point to salary history to justify paying an employee less, which just institutionalizes the discrimination," she said.

In the case decided Monday, plaintiff Aileen Rizo took a job as a math consultant in Fresno County in 2009 after working for several years in Arizona. The policy of the Fresno County superintendent of schools at the time was to add 5 percent to the previous salaries of all new hires.

The policy was "gender-neutral, objective and effective in attracting qualified applicants," Fresno County Superintendent of Schools Jim Yovino responded in a statement Monday saying he will appeal the ruling to the US Supreme Court.

Mr. Yovino said the policy was applied to more than 3,000 employees over 17 years and had "no disparate impact on female employees."

It's not clear how the school district in Phoenix where Ms. Rizo worked arrived at her previous salary. However, Ninth Circuit Judge Paul Watford said in a separate opinion that Fresno County failed to show her pay there was not affected by gender discrimination.

Rizo said Monday she cried "tears of joy" when she heard about the ruling. The decision overturned an opinion last year by a smaller panel of Ninth Circuit judges that was criticized by equal pay advocates.

A California law signed last year prohibits employers from asking job applicants about prior salaries – a policy adopted by a handful of other states and some cities. The measure is designed to narrow the pay gap between men and women.

Women made about 80 cents for every dollar earned by men in 2015, according to US government data.

The Equal Pay Act, signed into law by former President John F. Kennedy in 1963, forbids employers from paying women less than men based on gender for equal work performed under similar conditions. But it creates exemptions when pay is based on seniority, merit, quantity, quality of work, or "any other factor other than sex."

Fresno County argued that basing starting salaries primarily on previous pay was one of those other factors and prevented subjective determinations of a new employee's value.

The 5 percent bump encourages candidates to leave their positions to work for the county, it said.

Judge Reinhardt, however, said prior salary is not a "legitimate measure of work experience, ability, performance, or any other job-related quality."

The judge lamented what he said was the continued "financial exploitation of working women," calling it "an embarrassing reality of our economy."

In a separate opinion Monday, Ninth Circuit Judge M. Margaret McKeown said her colleagues were going too far in barring any consideration of previous pay, even in conjunction with other factors such as education and experience.

"Differences in prior pay may well be based on other factors such as the cost of living in different parts of our country," she said. "Also, it is possible, and we hope in this day probable, that the prior employer had adjusted its pay system to be gender neutral."

Rizo, who trained math teachers in the Fresno County district before leaving for another job, earned a little under $63,000 a year when she was hired. She learned that one male colleague with less experience, education, and seniority made nearly $13,000 more than her, she said.

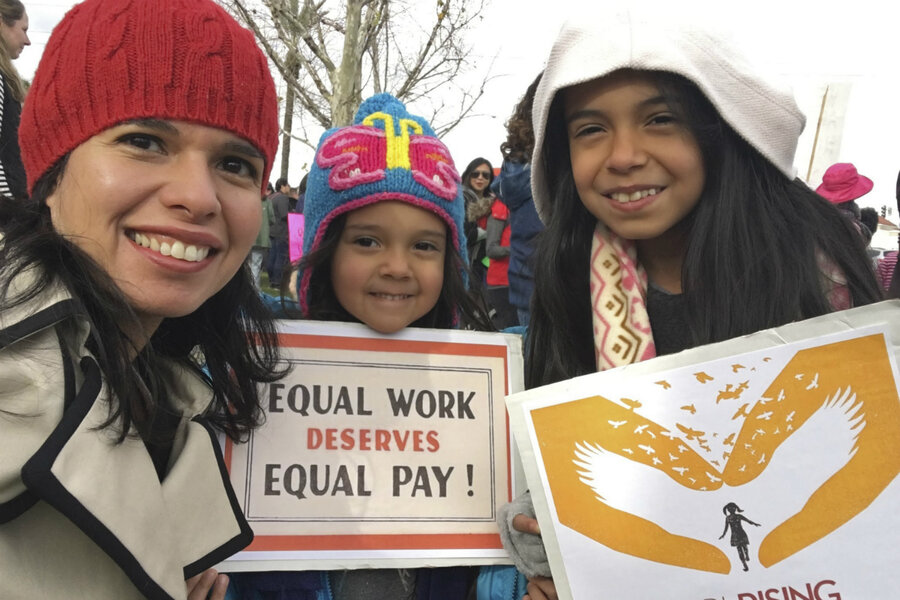

"This case is not about me," said Rizo, now an advocate for equal pay. "It's about all women and the chance that we have for pay equity when we're released from historically low wages that many women, especially women of color like myself, have been earning."

This article was reported by The Associated Press.