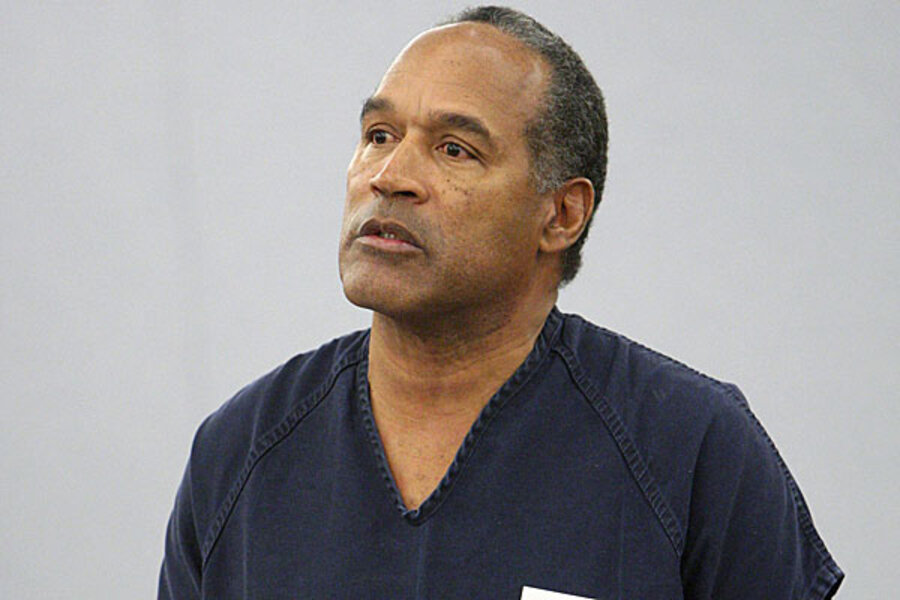

O.J. Simpson in court to fight robbery, kidnapping conviction

Loading...

| Las Vegas

Like a recurring nightmare, the return of O.J. Simpson to a Las Vegas courtroom come Monday will remind Americans of a tragedy that became a national obsession and in the process changed the country's attitude toward the justice system, the media and celebrity.

His 1995 trial is the stuff of legends, the precipitous fall of a Hall of Fame football player from the pinnacle of adoration to a murder defendant who, although acquitted of killing his ex-wife and her friend, was never absolved in the public mind.

He is arguably the most famous American ever charged with murder, and his "trial of the century" cast him in the role of the accused — no longer the superhero-turned-movie actor held up to young people as an example of achievement.

But less is remembered about the 2008 Las Vegas trial that sent Simpson to prison for a bizarre hotel room robbery in which the celebrity defendant said he just wanted to take back personal memorabilia that he claimed was stolen from him.

When he comes to court on Monday, it is that conviction for armed robbery and kidnapping that will be before a Nevada judge. Simpson is seeking freedom in what lawyers often call a "Hail Mary motion," a writ of habeas corpus. It claims he had such bad representation that his conviction should be reversed and a new trial ordered. Most defendants lose these motions, but in this case nobody is taking bets on the outcome.

"Nothing is the same when O.J. is involved," said Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson, who observed Simpson's Los Angeles trial. "An O.J. case is never like any other case."

With Simpson, the past is always a prologue — and so memories of his murder trial are certain to serve as a backdrop throughout the Las Vegas hearing. This case, while less dramatic in nature, carries with it far more devastating consequences.

Now 65 years old, Simpson has already spent the last four years in prison and must serve at least nine years of his maximum 33-year sentence before he is even eligible for parole. He would be 70 by then. If Simpson doesn't win a new trial, he could conceivably spend the rest of his life locked up.

"I try to explain to people how somebody could come from nothing to live the American dream and then lose it all," said Simpson's former manager and agent, Mike Gilbert, who is expected to testify at the hearing. "I have a hard time with it."

Close friend Jim Barnett describes Simpson as grayer, paunchier and limping a little more these days from old knee injuries. The Silicon Valley venture capitalist has visited Simpson several times at the medium-security Lovelock Correctional Center, an hour northeast of Reno.

Simpson, Barnett said, is a favorite among inmates. He has served as prison gym steward and coached a champion prison baseball team. "He gets along with everyone there," he said. "But he's slow. Last time I saw him, he had gotten quite heavy."

Before the "trial of the century," there were few televised court cases, no celebrity justice shows and a minimum of talking heads holding forth on TV about the prospects of famous defendants in court. Simpson's murder trial, televised from gavel to gavel, brought the legal arena into living rooms and turned lawyers into stars.

And Simpson, the quintessential American sports hero, was brought down by a trial that could not vindicate him even with a "not guilty" verdict. Too many people wanted him to pay for the deaths of his beautiful ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman, found stabbed in front of her Los Angeles condominium.

Too many people believed Simpson had gotten away with murder.

The man who had won the Heisman Trophy and was known for his phenomenal running on a football field — and in commercials for Hertz cars — ran again when he was named as a suspect in the June 1994 killings. The spectacle of police chasing after one of America's most famous men across Los Angeles freeways was an image for history books. The slow-speed white Ford Bronco pursuit became part of the legend.

It took a year for his trial to unfold. There were issues of racism, domestic violence, mishandled evidence — and the many memorable moments, and lines, that quickly became part of the pop culture lexicon: Simpson struggling to squeeze on a bloody black glove and his lawyer, Johnnie Cochran, admonishing the jury: "If it doesn't fit, you must acquit."

The case so captivated America that on the day of the verdict, even then-President Bill Clinton watched it on TV.

Simpson walked out a free man. But he would be a pariah forever after.

As shocking as Simpson's fall from grace is his involvement in the hotel room heist that landed him in prison.

Those who try to explain it come back to one word — hubris, the literary allusion to excessive self-confidence, pride and arrogance. Simpson refused to accept that people didn't idolize him anymore. He boasted about his continuing celebrity status. He was delighted that people still wanted his autograph and wanted to hang out with him at the pool of The Palms hotel in Las Vegas. And that was where the disastrous plan was born.

He had come to Las Vegas that September of 2007 for a happy event. His old friend, Tom Scotto, was getting married and invited Simpson to be his best man. Scotto still sounds anguished when he recalls the weekend.

"If it wasn't for me," Scotto said in an interview, "he wouldn't have been there."

Simpson, trial testimony would show, organized a posse of five friends and acquaintances to accompany him to a hotel where he was told some men were trying to sell his mementos, including family pictures. It was to be a sting of sorts, in which the memorabilia dealers would think an anonymous buyer was coming.

When Simpson walked into the hotel room, he realized he knew the sellers from previous dealings and he accused them of stealing from him. He shouted that no one was to leave the room — an action that would be judged to fit the legal definition of kidnapping. As Simpson's guys began bagging up the memorabilia, one of them pulled a gun, according to trial testimony.

No one was injured, but the sellers called the police — and another Simpson case for another century was launched.

It turned out that Tom Riccio, another memorabilia dealer who played middleman between Simpson and the sellers, had planted a tape recorder in the hotel room and the tape, played for jurors, was powerful evidence.

Simpson's cohorts testified against him, including the man who said he brought a gun. They were an odd assortment of down-on-their luck Vegas characters who received plea deals and were set free on probation.

Simpson's co-defendant at his trial, Clarence "C.J." Stewart, served more than two years in prison before the Nevada Supreme Court overturned his conviction. The justices ruled Simpson's fame tainted the proceedings and that Stewart should have been tried separately. Stewart took a plea deal to avoid a retrial and was released.

Simpson, meantime, was sentenced by Clark County District Court Judge Jackie Glass to nine to 33 years in prison. Referencing the earlier murder trial, the judge said that her penalty was not intended as "retribution or any payback for anything else." She made no mention of the two Las Vegas police detectives overheard in a taped conversation saying that if California authorities couldn't "get" Simpson, those in Nevada would. The tape was played at the trial.

On Monday, Simpson will be back before a different judge who agreed to hear evidence on 19 claims of ineffective counsel and attorney conflict of interest. Simpson contends his trial attorney never told him about a plea bargain that had been offered by prosecutors. He also said in a sworn statement that the same attorney knew about the memorabilia sting before it happened, and "he advised me that I was within my legal rights."

Simpson is expected to testify sometime during the weeklong hearing. Instead of wearing an expensive suit and tie, the man known to Nevada authorities as inmate No. 1027820 will be dressed in plain blue prison garb.

___

AP Special Correspondent and courts specialist Linda Deutsch has covered O.J. Simpson since 1994, attending every day of the Los Angeles and Las Vegas trials. Associated Press writer Ken Ritter in Las Vegas contributed to this report.

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press.