'If I win': Trump vows to accept election results, so long as he doesn't lose

Loading...

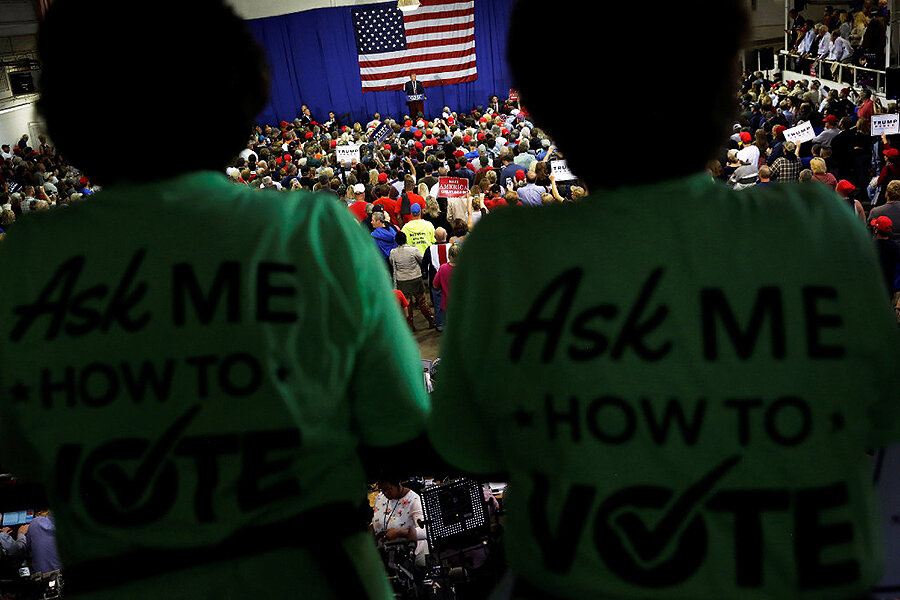

| Delaware, Ohio

Donald Trump kept floating the possibility Thursday that he'll challenge the results of the presidential election if there's a "questionable result," while teasingly promising to embrace the outcome "if I win."

The Republican presidential nominee said he would accept "a clear election result" but was reserving his right to "contest or file a legal challenge" if he loses. It was his first attempt to explain his stunning warning a day earlier in the final debate that he might not accept the results.

On Thursday, Trump brushed off the likelihood of that happening with a confident prediction that "we're not going to lose."

"I would like to promise and pledge to all of my voters and supporters and to all of the people of the United States that I will totally accept the results of this great and historic presidential election," Trump said. Then after letting that vow hang in the air, he added, "If I win."

Trump's musings about hypothetical Election Day scenarios came as his campaign was reeling from widespread astonishment over his refusal to commit to the time-honored American tradition of the election's loser acceding gracefully to the winner. Trump has warned repeatedly of impending, widespread voter fraud, despite no evidence to support him and plenty of evidence to the contrary.

Asked at the debate whether he'd accept the outcome, Trump said: "I will tell you at the time. I will keep you in suspense."

That ominous rejoinder sent immediate shockwaves through the campaign, as Trump's supporters tried to soften his remarks and fellow Republicans sought even more distance from their own nominee. The distraction deprived Trump of the comeback moment he sorely needed, despite a sometimes more-measured and poised performance in Wednesday's third and final debate.

The refusal can be seen as a test of American democracy itself, as The Christian Science Monitor's Linda Feldmann wrote on Thursday morning:

In one go, Trump cast into doubt the very foundation of democracy, that an election results in a peaceful transfer of power.

Trump may know full well how he will respond to the result of the Nov. 8 vote, which appears increasingly tilted toward a Clinton victory. But his strongest supporters don’t, and as Trump ramps up talk at his rallies of a “rigged election” and how Clinton is planning to steal the election, he raises the specter of post-election unrest and a corrosive sense that a President Hillary Clinton would be illegitimate.

The Republican National Committee, whose chief mission is to get the GOP nominee elected, was put in the remarkable position of disputing its own candidate, with a spokesman saying the party would "respect the will of the people." Even some of Trump's most ardent supporters felt it was a step over the line. Sen. Bob Corker of Tennessee said it was "imperative that Donald Trump clearly state" he'll accept the results.

Democrats piled on, hoping Trump's words would drag him down and Republican Senate and House candidates along with him. Though postelection challenges are not uncommon when few votes separate candidates, it's extraordinary for a candidate to raise the prospect before Election Day.

"The things that Donald Trump is saying and doing is genuinely a threat to the democratic process, which is based on trust," said Vice President Joe Biden as he campaigned for Hillary Clinton in New Hampshire. He said Trump was questioning "the legitimacy of our democracy."

As he entered the campaign's final stretch Thursday, Trump tried to turn the tables on Clinton by accusing her of "cheating" and suggesting she should "resign from the race." He cited a hacked email that showed Clinton's campaign was tipped off about a question she'd be asked in a CNN town hall meeting during the Democratic primary.

"Can you imagine if I got the questions? They would call for the re-establishment of the electric chair, do you agree?" Trump asked supporters at a rally in Ohio.

Trump's effort to shift the conversation back to Clinton centered on an email from longtime Democratic Party operative Donna Brazile to Clinton's campaign in March with the subject line "From time to time I get the questions in advance." It contained the wording of a death penalty question that Brazile suggested Clinton would be asked.

Brazile, now the acting Democratic National Committee chairwoman, was a CNN contributor at the time she sent the email, one of thousands disclosed publicly by Wikileaks after Clinton's campaign chairman's emails were hacked. Clinton's campaign has said Russia was behind the hack.

"She used these questions, studied the questions, got the perfect answer for the questions and never said that she did something that was totally wrong and inappropriate," Trump said of Clinton. He said that Brazile should resign as the head of the DNC.

All that was overshadowed by Trump's stunner about the election's results, which marked the culmination of weeks of escalating assertions that "this election is rigged" against him and that Clinton was trying "to steal it." Trump's campaign – and even his daughter – had tried to reframe his claim by insisting he was referring to unfair media treatment, leading Trump to contradict them by saying that no, he was referring to actual fraud.

There is no evidence of widespread voter fraud. U.S. elections are run by local elected officials – Republicans, in many of the most competitive states – and many of those officials have denied and denounced Trump's charges.

But Trump's campaign pointed to Al Gore and George W. Bush in 2000 as Exhibit A for why it would be premature for Trump to say he'd acquiesce on Nov. 8. Yet that election, which played out for weeks until the Supreme Court weighed in, didn't center on allegations of fraud, but on proper vote-counting after an extremely close outcome in the pivotal state of Florida led to a mandatory recount.

Mr. Lederman reported from Washington. AP White House Correspondent Julie Pace and AP writer Kathleen Ronayne contributed to this report.