Obama's position is that federal fracking regulations are compatible with increasing oil and gas production while preserving the environment.

"We have a supply of natural gas that can last America nearly 100 years, and my administration will take every possible action to safely develop this energy," Obama said in his 2012 State of the Union speech. "Experts believe this will support more than 600,000 jobs by the end of the decade. And I'm requiring all companies that drill for gas on public lands to disclose the chemicals they use. America will develop this resource without putting the health and safety of our citizens at risk."

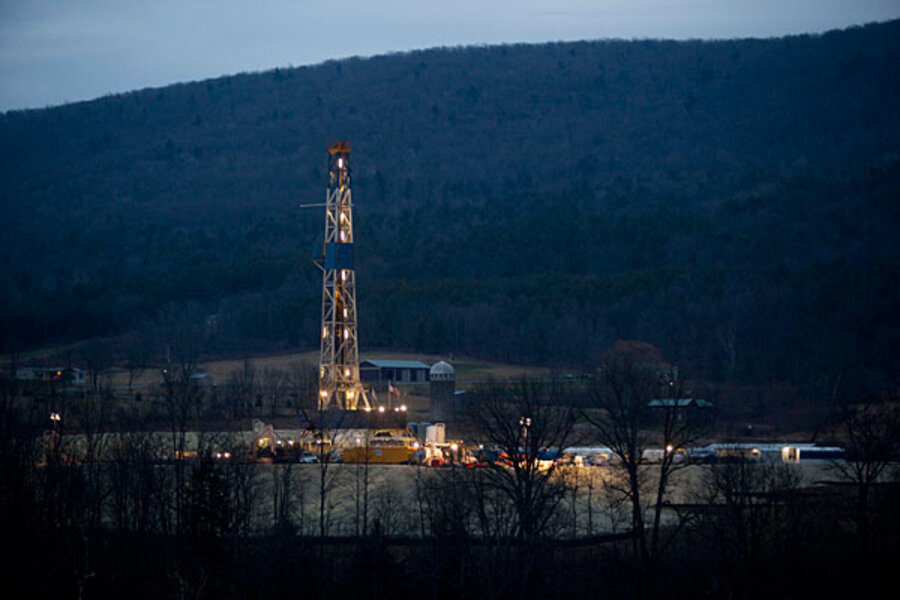

So far the boom in oil and gas from the fracking process has seemed little slowed, bringing the US an unexpected surge in natural gas as well as oil production over the past four years. Oil production in the US today is at an eight-year high, while oil imports have fallen from an all-time high of 13.5 million barrels per day (65 percent of demand) in 2005 to 9.8 million barrels per day or (52 percent of demand) last year.

Romney has staked out a position that federal fracking regulations are onerous.

"While fracking requires regulation just like any other energy-extraction practice, the EPA in a Romney administration will not pursue overly aggressive interventions designed to discourage fracking altogether," Romney's 2011 "Believe in America" plan says. "States have carefully and effectively regulated the process for decades, and the recent industry agreement to disclose the composition of chemicals used in the fracking process is another welcome step in the right direction. Of critical importance: the environmental impact of fracking should not be considered in the abstract, but rather evaluated in comparison to the impact of utilizing the fuels that natural gas displaces, including coal."