Why are NFL players walking away from the game so early?

Loading...

Following his junior season at the University of Washington, quarterback Jake Locker had National Football League franchises salivating.

He could pass, he ran a pro-style offense at Washington, and he was a freak athlete who could take off and scramble to extend a play with his feet.

After the 2009 college football season, Locker was considered to be in the conversation for the top pick in the 2010 National Football League (NFL) Draft, according to the Seattle Times. Instead he went back to school for a senior season where he did not experience the same level of success from the previous season, but the Tennessee Titans, in need of a quarterback still drafted Locker with their first round pick in the 2011 draft.

Now at age 26, Locker is retiring from the game, having dealt with nagging injuries and inconsistent play at the NFL level. Locker missed 14 of 32 possible starts, according to the Tennessean.

"I am retiring from football after much reflection and discussion with my family," Locker said in a statement obtained by the NFL Network. "I will always be grateful for having had the opportunity to realize my childhood dream of playing in the NFL and for the lifelong relationships I developed because of that experience. Football has always played a pivotal role in my life and I love the game, but I no longer have the burning desire necessary to play the game for a living; to continue to do so would be unfair to the next organization with whom I would eventually sign."

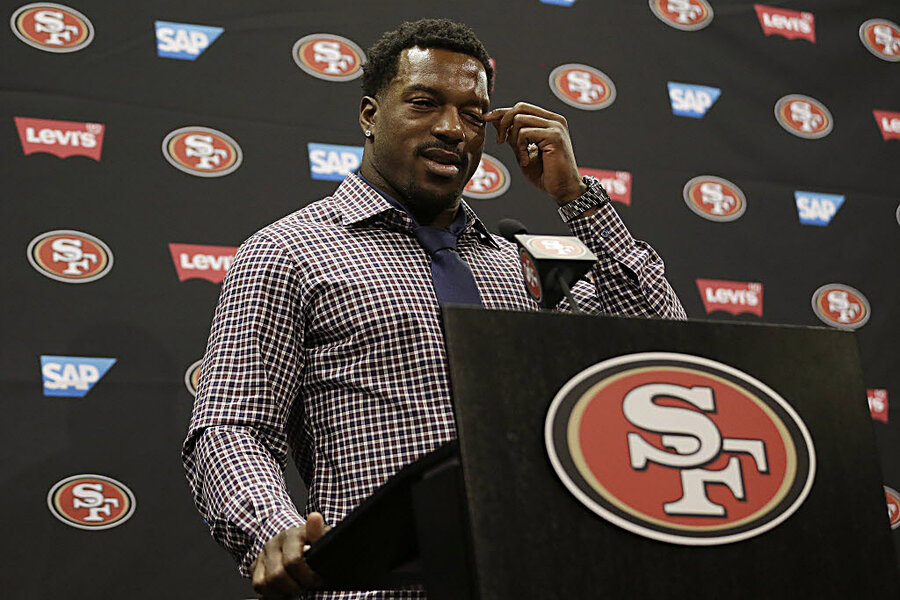

Locker is not the only notable player who has called it a career this offseason. San Francisco 49ers linebacker Patrick Willis, 30, retired last week. He had only played in six games this past season because of a left big toe problem. Willis has made more than $45 million over an eight year career and he decided that the physical cost of rehabbing his foot was not worth the return. Willis mentioned speaking to former NFL players who have trouble walking and playing with their kids. Willis wanted to leave the game with his health relatively intact, according to Yahoo! Sports.

"People see that and they feel sorry then, but nobody knows it’s because you played those few extra years that for whatever reason you chose to play," Willis said in his retirement press conference that was broadcast on the 49ers website. "It’s my health first, and everything else kind of just makes sense around it."

Football is a physically demanding game and the average lifespan of an NFL career is less than four seasons, according to Statista.com. So it is not uncommon every year to see a notable player hang it up a year or two before fans think a guy has nothing left.

Willis' retirement, however, is somewhat of a head-scratcher. He was a five-time All-Pro, seven-time Pro Bowler, and was considered by many in NFL circles to be on a short list of the best middle linebackers in the game. Willis claimed he did not feel like his legs were up for the wear and tear of hanging onto his football career for a couple more seasons that would fall short of his own expectations for himself, and did not want to simply cash game checks, Yahoo! Sports reported.

"It’s something about these feet," Willis said the press conference. "When you don’t have no feet – and that’s what made me who I am."

Football also takes a unseen toll on the mental well-being on the players. Concussions and their long term consequences have been getting more attention. More and more players are willing their brains to be studied upon their deaths, according to Fox Sports.

There has also been a spike in untimely deaths among former NFL players, most notably former Chicago Bears' safety Dave Duerson, Pittsburgh Steelers' center Mike Webster, and linebacker Junior Seau, who played for three teams over a 20-year career. Duerson and Seau both committed suicide, but preserved their brains for study. Webster died suddenly, but had been battling acute dementia, Frontline reported.

The Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalophy at Boston University has found evidence to suggest that repeated, compounding hits to the head, ranging from minor jolts between wrestling offensive and defensive linemen to violent tackles, contribute to a degenerative brain condition called Chronic Traumatic Encephalophy or CTE. Its symptoms include memory loss, depression, and dementia, according the center's research.

Going back as far as 1994, the NFL was aware of the possible long-term dangers concussions pose to those who suffer multiple head injuries that was profiled in the PBS Frontline report titled "A League of Denial." The Frontline report painted a picture of a league where concussions were treated like bad headaches on NFL sidelines. Now, with more available research, some players are saying the game is not worth the physical price.

Back in 2012, Jacob Bell who played as a guard on offensive lines for eight seasons, decided to retire from the game citing he did not want to further subject his brain to further hits and save his mental health for later in life, according to CBS News.

Whatever the reason for a professional athlete deciding to retire from the game, it leaves an empty hole in the athlete's life that was filled entirely by the sport he or she spent their life perfecting. Yahoo! Sports reports that as accomplished a player as the 49ers' Willis was, not being able to play football at a elite level meant it was time for him to walk away.

"I feel like I have no regrets standing up here today, as I had no regrets yesterday and the day before, as I know I’ll have no regrets tomorrow," Willis tearfully said in his press conference. ""Because one thing I’ve always lived by is giving everything you’ve got today so when you look back tomorrow you don’t feel ashamed because you left anything on the table. I feel like there will not have been a day in my career when I don’t feel like I gave the game everything I had."