Friend of Boston Marathon bombing suspect convicted of obstructing justice

Loading...

| Boston

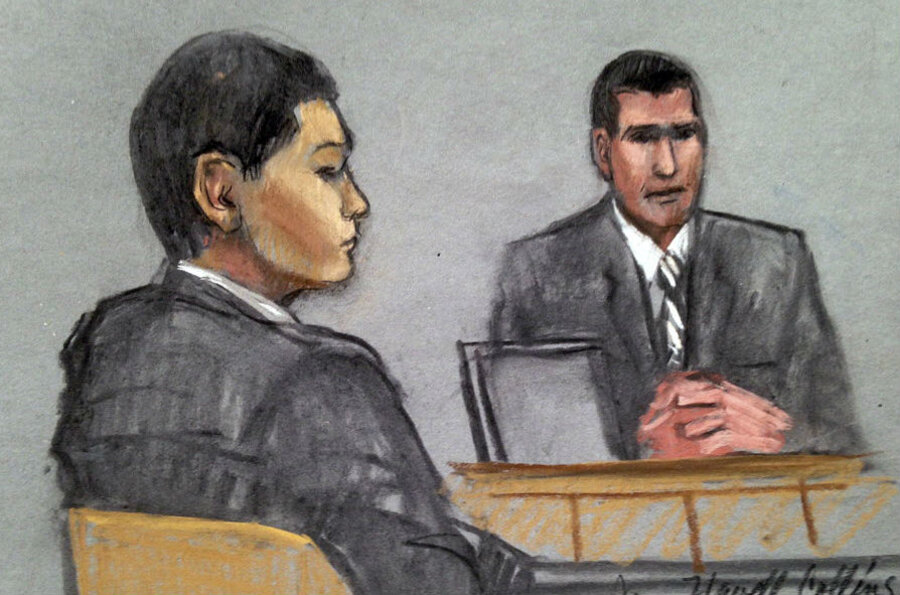

A former classmate of Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was found guilty on Monday of hiding evidence that could have shed light on the incident in the hours following the 2013 attack.

A federal jury convicted Azamat Tazhayakov of one count of obstructing justice and one count of conspiracy to obstruct justice, but it found him not guilty of two other obstruction charges.

Though the convictions could land Mr. Tazhayakov in prison for up to 25 years, the defendant remained relatively stoic as the verdict was read, momentarily lowering his head into his palms, while his mother sobbed openly.

During the trial, which began July 7 and lasted two weeks, prosecutors and defense attorneys agreed on a basic timeline of events following the April 15 bombings – although the two sides interpreted Tazhayakov’s motivations in starkly different terms.

Tazhayakov – along with two other friends of Mr. Tsarnaev, Robel Phillipos and Dias Kadyrbayev, both of whom are to be tried in September – was accused of helping to remove a number of incriminating items from Tsarnaev’s dorm room in Dartmouth, Mass., on the evening of April 18. Those items included fireworks emptied of gunpowder and a laptop computer.

That evening, Mr. Kadyrbayev threw Tsarnaev’s laptop in the trash, while Tazhayakov repeatedly searched the Internet for information on the bombing. Tazhayakov would later text Kadyrbayev, writing that he believed the authorities had caught Tsarnaev’s brother, Tamerlan, hours before such information was made public.

Defense attorneys said that Tazhayakov, along with Mr. Phillipos, was a passive onlooker, who merely watched as Kadyrbayev disposed of Tsarnaev’s things. They also said that the defendant – an exchange student from Kazakhstan – failed to understand the seriousness of the situation, falling victim to cloudy adolescent judgment and a lack of cultural context.

“The reality is: College kids think differently,” Matthew Myers, an attorney for Tazhayakov, said during closing arguments on July 16. “I’m not minimizing what happened in this town in the least, but when you’re talking about college kids, you’re talking about a different mind-set.”

According to prosecutors, the earliest evidence of the obstruction charge stemmed from a text message that Tsarnaev sent to Tazhayakov just before 9 p.m. on April 18 that read, “Ifyu want yu can go to my room and take what’s there :) but ight bro.”

While prosecutors said the text was a signal for Tazkayakov to remove the emptied fireworks from his room, defense attorneys said the smiley face was code for marijuana – the use of which emerged during testimony as a central aspect of Tsarnaev and Tazhayakov’s friendship.

Over the course of the two-week trial, a picture of both Tazhayakov and Tsarnaev as carefree, pot-smoking college students came to the fore. According to Bayan Kumiskali, Kadyrbayev’s girlfriend, the relationship between the two centered on weed, hanging out, and occasionally playing soccer.

This laid-back portrait of Tsarnaev added another layer of complexity to the suspected bomber's persona, whose practice of Islam apparently radicalized during his first and only year at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, even as many of his friends said they were unaware that he was deeply religious.

He began to discuss religious extremism with Tazhayakov in the months leading up to the attack, extolling the virtues of martyrdom to his friend and alluding to bombmaking techniques.

“My religion is my truth,” read one of Tsarnaev’s tweets, highlighted in a Rolling Stone profile in June 2013.

“I don’t argue with fools Islam is terrorism it’s not worth a thing, let an idiot remain [an] idiot,” read another.

The 12-person jury in the Tazhayakov case deliberated for 15 hours over three days, with one interruption when a juror became ill on Friday. Sentencing is scheduled for Oct. 16.

Tsarnaev is scheduled to go on trial in November. The location of that trial is still up in the air, however, as lawyers for the bombing suspect requested a change of venue in June, citing an “overwhelming presumption of guilt” in Massachusetts.

Tsarnaev stands accused of planting two pressure-cooker bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013, an attack that killed three and injured at least 264. If convicted, he could face the death penalty.

• This report includes material from Reuters and The Associated Press.