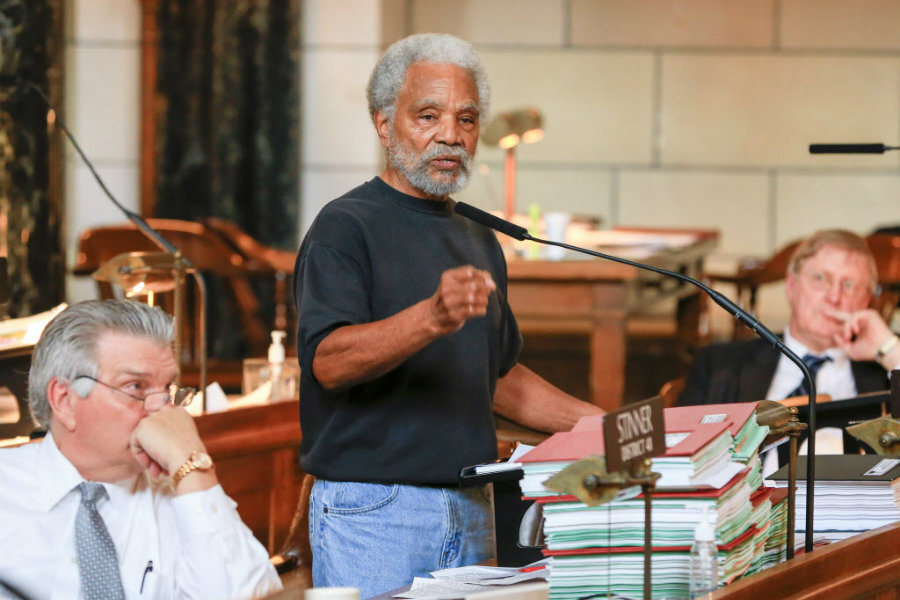

Nebraska death penalty repeal: Are Republicans shifting their stance?

Loading...

Nebraska’s days as a death penalty state may be coming to an end.

Lawmakers on Wednesday approved a bill to repeal capital punishment, making Nebraska the first conservative state to do so in more than 40 years. The vote – which marks a shift toward bipartisan agreement about policy surrounding the death penalty – could pave the way for similar decisions in other Republican states, as support for capital punishment continues its slow decline across the United States.

“The conservative Republicans’ positions as expressed in Nebraska are basically a microcosm of what’s going on with conservatives about the death penalty nationwide,” says Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, a national nonprofit that provides information and analysis related to the death penalty. “Abolition in Nebraska could empower conservatives in other 'red' states to move forward because they know it can be done.”

Procedural, fiscal, and religious concerns are driving the shift, Mr. Dunham says.

In Nebraska, where lawmakers voted 32 to 15 in favor of abolition – enough to override an expected veto from Gov. Pete Ricketts – the bill’s Republican supporters appeal to fiscal conservatism, casting the death penalty "as a waste of taxpayer money and question whether government can be trusted to manage it,” the Associated Press reported.

Studies have shown that the costs associated with cases that seek the death penalty are often far greater than in cases that don’t. One Seattle University report published in January estimated that death penalty trials and subsequent appeals can cost taxpayers up to $1 million more.

“What this provides is evidence of the costs of death-penalty cases, empirical evidence,” the study’s lead author Peter Collins told the Seattle Times. “We went into it [the study] wanting to remain objective. This is purely about the economics; whether or not it’s worth the investment is up to the public.”

Some Republican lawmakers have also questioned whether support for the death penalty conflicts with conservative values about preserving life and opposing government intervention.

“It's certainly a matter of conscience, at least in part, but it's also a matter of trying to be philosophically consistent,” Sen. Laure Ebke, (R) of Crete, told the AP. “If government can’t be trusted to manage our health care ... then why should it be trusted to carry out the irrevocable sentence of death?”

The system that makes the death penalty possible has also come under scrutiny in the face of the scarcity of lethal injection drugs and recent botched executions. Nebraska, for instance, lacks the drugs it needs to execute any of its 11 death-row inmates, and the last execution in the state was in 1997, The Wall Street Journal reported.

“If any other system in our government was as ineffective and inefficient as is our death penalty, we conservatives would have gotten rid of it a long, long time ago,” Sen. Colby Coash, (R) of Lincoln, told the Journal.

Some victims’ families have also recently come out against the death penalty, saying that the years of appeals did little to help them heal or move forward. During the trial of convicted Boston marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Bill and Denise Richard, whose 8-year-old was killed in the attack, publicly spoke against the prospect of a death sentence for Tsarnaev.

“The continued pursuit of that punishment could bring years of appeals and prolong reliving the most painful day of our lives,” they wrote in an essay for The Boston Globe. “The minute the defendant fades from our newspapers and TV screens is the minute we begin the process of rebuilding our lives and our family.”

Not everyone is in favor of abolition. Nebraska Gov. Ricketts, who announced last week that the state had bought new lethal injection drugs, has pledged to veto the bill, requiring an override vote.

“This is a case where the Legislature is completely out of touch with the overwhelming majority of Nebraskans that I talk to," Ricketts told the AP.

The most recent Pew Research Center numbers also show that nationally, more than three-quarters of Republicans still favor capital punishment, compared to only 40 percent of Democrats.

Still, conservative opposition to the death penalty is increasingly present. Even in Texas – the top state for executions, with more than 400 since 1976 – death sentences have been on the decline: The state executed 35 people in 1999 compared to 10 last year.

“There is no doubt about it. We’re seeing a reduction in the use of the death penalty in Texas,” Kathryn Kase, executive director of the nonprofit Texas Defender Service, told The Dallas Morning News earlier this month.

“Here it is May, and we have had only two death penalty cases in Texas,” Ms. Kase added. “And in both, the jury chose life without parole instead. That strikes me as really significant.”