January 1991: Somali President Siad Barre's government is forced from power. By November, a struggle among clan warlords pushes Somalia into civil war. In the meantime, thousands of civilians die of starvation in a region-wide drought.

February 1992: Rival commanders sign a UN-sponsored cease-fire. And the UN deploys peacekeepers under a newly created United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) to observe the cease-fire.

But fighting continues to escalate. In December, US Marines join UNOSOM.

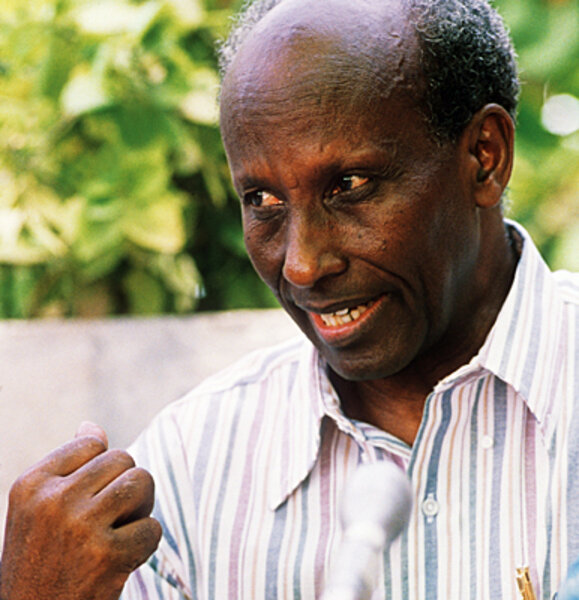

1993: US forces target Somali warlord Mohammed Farah Aidid, who along with his rival warlord Ali Mahdi Mohamed are using food aid as a lever for power. About 2,000 people are killed in clashes between the US marines and Aidid's forces.

June 1993: 24 Pakistani peacekeepers with UNOSOM are killed by forces loyal to Somali warlord Aidid. This prompts nothing. The UN continues to operate as before.

October 1993: 17 US army rangers are killed in the famous “Black Hawk Down” incident, when US helicopters are shot down in Mogadishu, and the Rangers mount a rescue mission.

March 1994: The US ends its mission in Somalia. A year later, the UNOSOM mission ends in failure.