Petrocaribe: Paying beans for Venezuelan oil

Loading...

| Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Each day, the oil refinery here pumps out the gas and petroleum products that bolster this Caribbean country's tourism-based economy – thanks to Venezuela.

That South American oil giant has kept the so-called black gold flowing in the Dominican Republic as part of the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez's brainchild: sending foreign countries oil under preferential repayment terms.

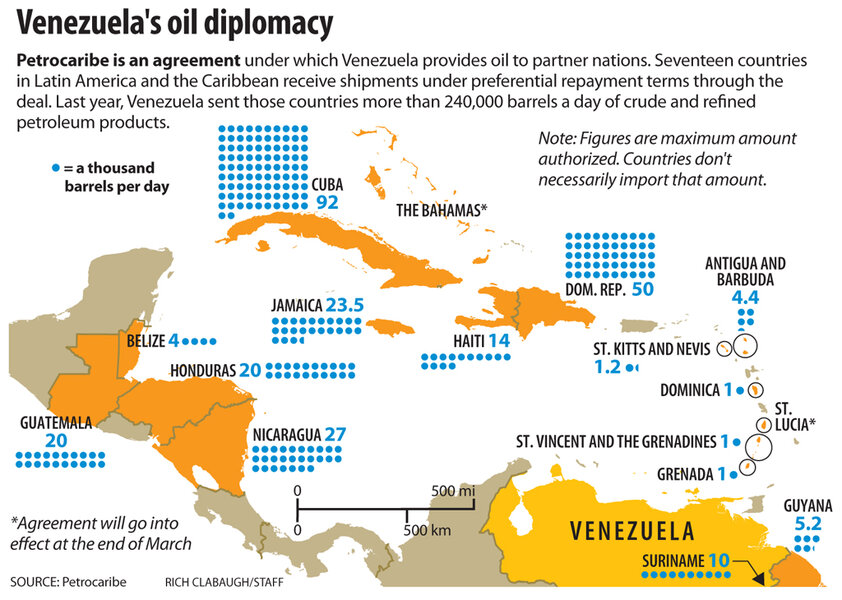

Last year, the Chávez government sent some 240,000 barrels a day to countries in the region – regardless of whether their politics fell in line with Mr. Chávez's socialistic ideals.

Some 18 mostly small countries, including Venezuela, are members of Petrocaribe. It is an energy pact under which members receive shipments of crude or refined oil products from Venezuela that they pay for over the course of 25 years at minimal interest rates.

But Chávez's death has sparked concerns that a new government may turn off the spigot.

If that happens, everything from construction of new highways to the price of gas and electricity and tax rates could be affected in the Dominican Republic, threatening to undermine its economy.

"Any cut to Petrocaribe would be disastrous for countries" that receive Venezuelan oil under such deals, says Jorge Piñon, an energy analyst and Caribbean specialist at The University of Texas at Austin. "It's become an integral part of their economies."

Venezuela's 'petrodiplomacy': free oil

Cuba has been long held up as the poster child for Venezuela's "petrodiplomacy," because it receives 92,000 barrels a day of petroleum products from its political ally. But the communist country is hardly alone in its dependency on Venezuela's reserves.

The Dominican Republic is allowed to import 50,000 barrels a day, second only to Cuba under Petrocaribe.

There was a tenuous sense of relief in the Dominican Republic when the interim government of Venezuela said this month that it would honor the Petrocaribe agreement, at least in the short term.

"The Petrocaribe accord will continue," the front page of a Dominican newspaper proclaimed after the announcement.

Propping up Dominican Republic economy

The Dominican Republic's politics differ drastically from those of Cuba, its Caribbean neighbor. But it never hid its partnership with Venezuela or its leaders.

In 2009 Venezuela bought a 49 percent stake in the Dominican Republic's state-run refining company, known as Refidomsa. That investment has helped keep the refinery running despite the fact that analysts say it should have been shut down for reasons of cost efficiency. The refinery itself runs on oil, rather than the cheaper natural gas that most modern refineries use.

But that's just part of Venezuela's contribution to the Dominican economy. Roughly 40 percent of the country's energy requirements are fulfilled by Venezuela. The Dominican government takes the Venezuelan oil, refines it, and then sells the products to the local market. By doing so, it's able to both keep gasoline prices down and subsidize the budget to the tune of more than $500 million a year.

Under a deal struck with Chávez, the Dominican government does pay for the crude it has received daily in recent years – but not necessarily in cash.

Last year, the Dominicans sent beans, literally: 10,000 tons of black beans headed to Venezuela to repay the petroleum debt. What's more, to plant those beans the Dominican government had to import seeds from the United States – which has frigid diplomatic relations with Venezuela.

Most Dominicans are far more worried about the future of Venezuelan oil shipments than the more than $3 billion the Dominican government owes Venezuela for the debt it's accumulated.

"Long live Chávez," says Wilson Cabrera, a cabdriver in the capital, Santo Domingo. "May his generosity continue."