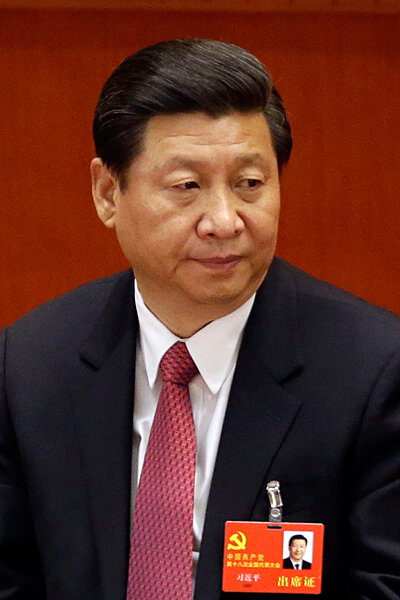

Xi Jinping was regarded as a shoo-in for the top leadership post, replacing Hu Jintao as General Secretary of the party Nov. 15, and as national president in March 2013.

Born into Communist aristocracy – his father was a revolutionary hero – Mr. Xi has also seen another side of life. When his father fell foul of Mao Zedong, the 15-year-old Xi was “sent down” to the countryside, and spent seven years in a remote village. Later, as a young party cadre whose career was already under way, he volunteered to work in a rural backwater rather than in the comfortable corridors of power in Beijing where he might have stayed.

Xi is known to have a personable, confident character that has served him well in a career during which he has not made any really powerful enemies – the best way to the top in consensus-ruled Chinese politics.

He studied chemistry at the prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing, and as he moved up the ladder – from deputy mayor of the industrial port of Xiamen, to deputy governor of Fujian Province to party boss in Zhejiang Province, he built a reputation for attracting investment, being open to private business, and for being an effective leader.

“He’s the kind of guy who knows how to get things over the goal line,” former US Treasury Secretary and Goldman Sachs boss Hank Paulson, who has dealt extensively with Chinese leaders, once commented.

Xi served briefly as party chief in Shanghai, clearing up the aftermath of a corruption scandal, before being put in charge of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, whose success further burnished his reputation. He was named to the Politburo Standing Committee in 2007 and is one of only two members staying on.