South Korea: The little dynamo that sneaked up on the world

Loading...

| Seoul, South Korea

For months the young emperor to the north has been threatening to turn this thriving metropolis into a "sea of fire." But it's not easy to ruffle the jaunty vibe of 75-year-old Kim Chong-shik as he strolls among young couples and shoppers along the boutiques of the Gangnam District.

Living well, it's said, is the best revenge. "I never imagined it would be like this," he says, grinning, not far from a playfully misplaced sign on a coffeehouse: Beverly Hills City Limits.

The retired civil servant, who remembers the Korean War and its miserable aftermath, cuts a dapper figure against a springtime cold snap, a green silk scarf peeking out from his handsome wool overcoat.

Why so stylish? "Because I live here!"

Ten million people live in Seoul, the heart of a huge sprawl that is home to half of the Republic of Korea's 49 million people. It is a hard-charging, high-pressure, high-tech hub of the 21st-century global economy – and sits in the cross hairs of an enemy who seems unaware the cold war ended a generation ago. North Korean missile installations are just 30 miles away – and now the threats are nuclear.

Yet not long ago, the dream of a single Korea – reconciled in peace like Germany, not through war like Vietnam – seemed like a destiny within reach. As recently as two months ago, Koreans from the south were still crossing the demilitarized zone (DMZ) to go to work alongside 50,000 northerners at the Kaesong industrial park, a legacy of the South's old "Sunshine Policy" of reconciliation. The Kaesong facility opened four years after athletes from both Koreas marched into the 2000 Sydney Olympics under a flag depicting a united peninsula. That same year South Korea's president was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. And Koreans have long embraced the idea that they are of "one blood." A January 2011 survey by the Korean Broadcasting System found that 71.6 percent of South Koreans favored reunification, and nearly as many said they would be willing to pay taxes to support it.

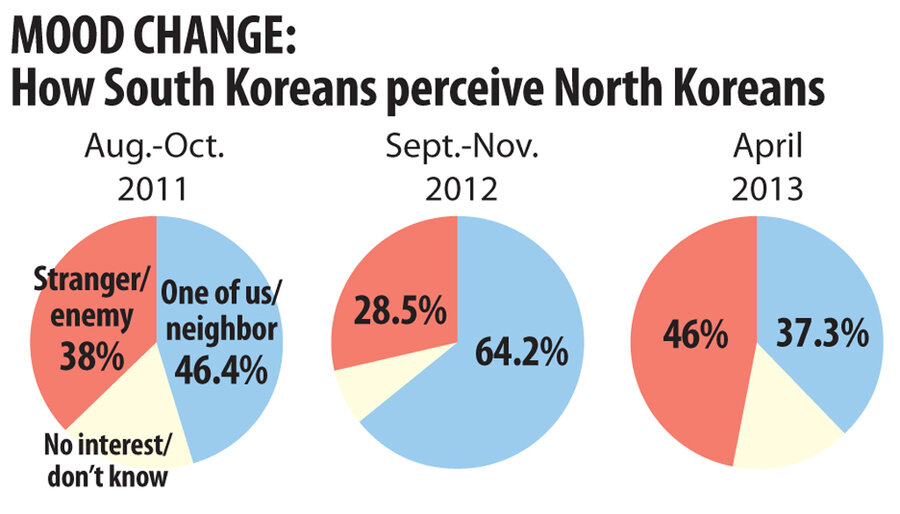

But the ardor for reunification has cooled with a new round of tensions this year. Pyongyang's threats appear to have decimated the southerners' goodwill: In just six months there was a precipitous drop in the number of South Koreans who consider northerners a "neighbor" or "one of us," from 64.2 percent as late as November 2012 to 37.3 percent in late April, and a spike to 46 percent considering northerners as strangers at best, if not enemies.

North Korea's new weaponry and "Supreme Leader" Kim Jong-un's bombast – including recent nuclear and missile tests – raise fears that a single Korea might happen in the worst way possible, through horrible violence.

Thoughts of a path to unity make Kim Chong-shik's smile disappear: "I worry about it a lot. We've gone in opposite directions. The differences are so great. It would be very difficult."

A hip prosperity

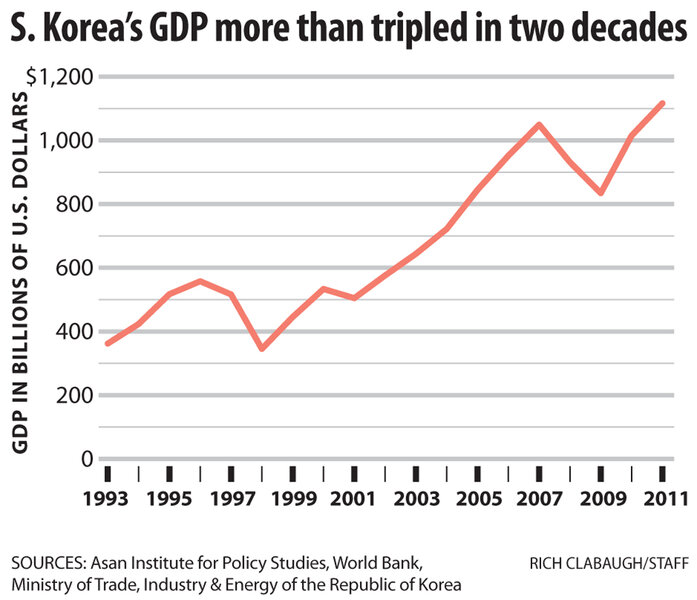

South Korea has never been so prosperous, so gregarious, so hip – so much so that it seems as if the nation sneaked up on the world.

As "the American century" fades, and the 21st century is said to "belong to China," it may make more sense to speak of "the Asian century" – and now is South Korea's moment. And in that moment, it shines in such stark contrast to the sad state of North Korea – so impoverished its people literally stand a few inches shorter than their southern cousins. The peninsula's bipolar condition is reflected most aptly in its leading personalities. The stocky K-pop party rocker Psy spreads "Gangnam Style" to the world while the North's pudgy supreme leader, like his father and grandfather before him, spreads menace, Pyongyang style.

The nuclear saber-rattling may have prompted the United States in March to add B-52 and B-2 stealth bombers to its annual military exercises with South Korea, but there are few outward signs of distress among South Koreans themselves. Seoul's stock market took it all in stride, and 50,000 Psy fans jammed a Seoul stadium for a mid-April concert that premièred his new song and video "Gentleman," in which Psy does not seem gentlemanly at all. Nobody expects him or any act, anywhere, to soon top the 1.5 billion-plus YouTube viewings of "Gangnam Style."

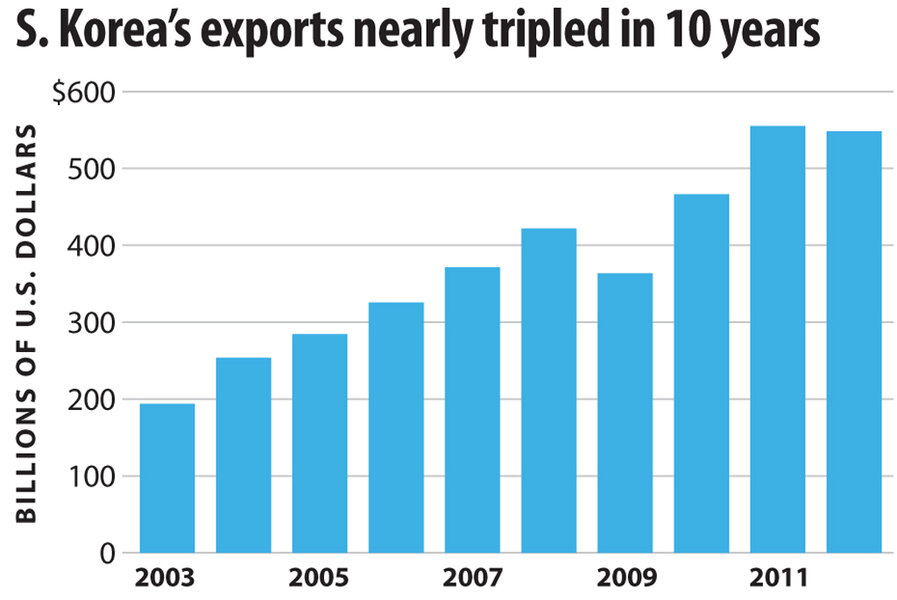

Psy's global success has made him a national hero. He is, in a sense, a flamboyant, fun-loving, globe-trotting version of the "industrial warriors" hailed by South Korean politicians for transforming this small nation into an economic powerhouse. While the Korean Wave exports K-pop and TV and film dramas far and wide, the rest of South Korea Inc. keeps cranking out computer chips, smart phones, TVs, autos, oil tankers, and container ships, while also building skyscrapers, highways, and shopping malls at home and abroad. In the first quarter of 2013, as Pyongyang started to act up, South Korea's gross domestic product jumped markedly over recent quarters. Samsung Electronics recorded a 42 percent spike in profits in its sixth straight quarter of growth as it pulls away from Apple in the smart-phone market.

South Koreans, clearly, aren't easily distracted. At Hyundai Motor Group headquarters, Doh Bo-eun, a mild-mannered economist and father of teenage girls, explains that it's pointless to dwell on Pyongyang when his duty is to study how the European Union's troubles may affect auto exports.

Over at the entertainment firm CJ E&M music division president Ahn Joon likens North Korea's threats to a mild illness, and says he worries more about ways to keep K-pop popping. That's why the colorfully coiffed Wonder Boyz put in marathon rehearsals at a Gangnam studio, working to make it big before they must report for compulsory military duty. [Editor's note: The original version erroneously identified CJ E&M as Psy's label.]

Until recently, South Korea only seemed to make news when North Korea caused trouble. Today's confrontation may portend more than the lethal violence of 2010, when 46 South Korean sailors were killed in the sinking of the naval vessel Cheonan, and later two marines and two civilians were killed in the shelling of the Yeonpyeong Islands. (North Korea denies being responsible for the sinking; an international investigation concludes it was.) At that time, South Korea's cooler heads prevailed, opting for a measured military retaliation against North Korean gun positions and vowing harsher payback for further attacks. The vow continues under newly elected Park Geun-hye, the nation's first female president and the daughter of a former military dictator credited with laying the foundation for South Korea's success and creating its Ministry of Unification. Yet even after the sinking of the Cheonan, Ms. Park's predecessor, President Lee Myung-bak, was optimistic enough to propose a "reunification tax" to prepare the country for its likely destiny.

Korean nationalism is a potent force, whether it refers to one nation, the other, or the imagined third. Yet for much of its history Korea has been dominated by foreign powers. In the first great war of the 20th century, Japan shocked the Western world when its forces throttled Russia to strengthen its domination of the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria – a part of the Korean "Hermit Kingdom."

South Korea's population is 2/5ths the size of Japan's, 1/7th the size of the US's, and 1/26th the size of China's, but pound for pound, it's outpunching the economic heavyweights. Once also-rans, companies like Samsung Electronics, LG, and Hyundai Motors are going toe-to-toe with the likes of Apple, Intel, Sony, Toyota, and Ford. Critics point out that Apple defeated Samsung in a high-profile patent case last year. Silicon Valley has long portrayed South Korea as "a fast follower," better at imitating than innovating. Samsung, however, is adept at collaboration: Apple used its chips in the iPhone, while Samsung's smart phones run Google's Android operating system. And Samsung has bragging rights to the No. 1 market share in TVs and memory chips – as well as one of the world's biggest arsenals of patents.

South Korea's tech know-how has also helped drive its success in entertainment. It was the Chinese, in the late 1990s, who first fell hard for Korea's TV melodramas and other entertainment, dubbing it hallyu – Korean Wave, which has since spread globally by satellite and Internet, winning fans in Europe, the Americas, and the Arab world. South Korea was early to embrace the Internet, rewiring Seoul for lightning-fast connections in the 1990s. [Editor's note: The original version erroneously identified the word hallyu as being a Mandarin term; it is a Korean moniker.]

While Psy and several other Korean stars are original talents, K-pop has also thrived through its "idol" model. Mr. Ahn, the music executive, is matter-of-fact about the starmaking machinery that casts young talent for girl groups that resemble Korean Barbies and boy groups that look like Japanese anime characters. The songwriting formula requires English lyrical hooks for wider appeal.

South Korea's export-dependent economy faced a stiff test in the 2008 financial meltdown and the global recession – and held up remarkably well. Data compiled by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows that South Korea's growth slowed to 0.3 percent in 2009, but the nation, unlike most, never slipped into recession. From 2004 to 2011, its unemployment rate never rose above 3.7 percent while income per capita soared 36 percent, to $30,366. South Korea's yin and yang of capitalism and socialism, meanwhile, has long provided universal health care and other safety-net benefits.

Not all news is upbeat. South Koreans' new affluence also produced a housing bubble and an unwise tendency to splurge on status symbols. When Psy sings "Hey, sexy lady," he is lampooning Seoul's strutting nouveau riche. High household debt is considered South Korea's greatest domestic economic challenge. Along with Louis Vuitton, Prada, and other chic brands, signs of affluence include $15 cups of gourmet coffee and occasional glimpses of women wearing hoods to obscure their recovery from cosmetic surgery. South Korea is the world's per capita leader in nipping and tucking, with Westernized eyes especially popular.

South Korea also holds a grimmer global distinction: It is No. 1 in suicides per capita among the 34 nations in the OECD – and by a wide margin. The rise has been startling and hard to understand. A 2012 report (based on data from 2010), put South Korea's suicide rate at 33.5 per 100,000 people, up from 28.4 in 2009.

Explanations are elusive. As in many Asian cultures, a high premium is placed on reputation, or "face." In one report, South Korea's Ministry of Health and Welfare cited "complicated socioeconomic reasons and a growing number of one-person households" as contributing factors. As South Korea has become more affluent and image-conscious, the flip side of success may be financial ruin and shame. Notably, in 2009, a year after he left office, former President Roh Moo-hyun committed suicide by leaping off a cliff amid allegations of corruption.

At the elite Korean Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, there have been a half-dozen suicides in recent years. Misgivings are expressed about a driven, ultracompetitive culture that produces students who score 97 percent on an exam and consider it a failure. [Editor's note: The original version implied that the suicides at the Korean Advanced Institute of Science and Technology were not publicized. They were.]

"Too many young people are very unhappy," says Han Sang-geun, a math professor. "If they don't succeed, you know, they are devastated."

Once a foreign aid recipient, now a donor

Time was that Koreans considered rice a luxury. During the Korean War and for many years after, recalls retired Army Maj. Gen. Ahn Kwang-chan, his village survived on a gruel of barley, which is much easier to grow than rice. Meat was for special occasions.

Well into the 1970s, South Koreans were in worse shape than their northern cousins, who benefited from ties within the Communist sphere. South Korea depended heavily on foreign aid, mostly from the US, including payment for more than 300,000 soldiers who fought communists in Vietnam. Today, South Korea is the world's only nation that has transformed itself from major recipient of foreign aid to major donor – with North Korea as a beneficiary.

The rags-to-riches tale is sometimes called "the Miracle of the Han River," the waterway that curves through Seoul and empties at an estuary on the DMZ. (Gangnam means "south of the river.") But the wellspring of the nation's success, many say, can be traced to a different han. The word signifies a distinctly Korean pain – the sorrow, anger, and unresolved injustice borne of subjugation. A prime example: the 200,000 "comfort women" of World War II forced to provide sex to Japanese soldiers.

The Allied victory liberated Korea from Japan but added new layers of han. The Ko-reans were divided by rival superpowers, creating conditions for fratricidal war five years later that began with an invasion ordered by North Korea's Kim Il-sung, whose grandson now leads the Pyongyang regime. The South's soldiers included Park Chung-hee, who in 1961 would seize power in a South Korea military coup and later prevail in an election to formally claim the title of president. The first President Park was an authoritarian figure who threatened to jail the patriarchs of the country's most powerful families – and later worked with them to create the chaebol system of conglomerates to develop the nation's export-oriented economy. Only 15 years ago, near the dawn of the Sunshine Policy, the Asian financial crisis threatened to crash South Korea's banking system and bring the miracle to an abrupt end. The country was vulnerable in part because the chaebols were considered too big to fail.

"It was the survival of the fattest," explains Tcha Moon-joong, a director at the government-backed Korean Development Institute. On the brink of ruin, South Korea accepted $47 billion in emergency loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). South Korea Inc. was stripped down and rebuilt. Four wasteful chaebols were dismantled, with Daewoo selling its auto works to General Motors. Samsung, Hyundai, and others restructured. The result: a leaner, tougher economic machine.

The IMF's, however, wasn't the only help that South Korea received. Thousands of Ko-reans like taxi driver Yoo Man-su lined up to donate gold jewelry and heirlooms to shore up the nation's reserves. Athletes donated gold medals. In raw monetary terms, the value was modest – but the collective emotional message was powerful. Several Asian countries were in crisis, but only South Koreans had this response. More recently, "when Greece got into trouble, the Greeks reached for rocks and threw them," Mr. Tcha points out. "Here, the people reached for gold and gave it to help the nation."

Such was the patriotism and the sense of sacrifice of the han generation. The Gangnam generation, Tcha says, lacks that "hungry spirit."

Leno can't kick Hyundai around anymore

At Hyundai headquarters, Choi Myoung-wha, vice president of marketing strategy, remembers her days at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va., and laughing about Jay Leno's Hyundai jokes. ("Researchers have discovered a way to double the value of a Hyundai. Just fill it up.")

Today Hyundai Motors is the world's fifth largest automaker, in part because of its reputation for quality – even if it did issue a massive recall in April regarding faulty air bags. Hyundai put an end to the jokes in 1999 with a "bet the company" move that paid off: "America's Best Warranty" – a 10-year, 100,000-mile guarantee.

Hyundai and its sister Kia line are ubiquitous in South Korea, but its global reach may be more impressive. Last year, Hyundai's newest factory, in Brazil, started producing hatchbacks designed for the South American market. The new facility signified the completion of a strategy that had already put factories in Russia, India, and China – the so-called BRIC group of large, fast-growing economies. Hyundai has three factories in China, Ms. Choi says, capable of pushing 1 million cars per year into what is already the world's largest auto market. It also has factories in the Czech Republic, Turkey, and the US, in Alabama.

The ground floor of Hyundai headquarters here doubles as a showroom for leading models such as the Sonata hybrid and popular Elantra. Another display promotes its hydrogen-powered, zero-emission car. Hyundai boasts that it is the first carmaker to introduce the assembly-line production of such vehicles, to fulfill orders from progressive Scandinavian governments.

Choi dismisses the rap that South Korea is merely a fast imitator, considering the innovations coming from Hyundai and Samsung. Now South Korea has become a trendsetter, and the Galaxy smart phones and K-pop have indirectly helped the nation's auto industry.

"The Korean Wave clearly plays into the country-of-origin effect," she says, "and does so in a very positive way."

South Korea's collective success, she suggests, reflects a lesson described in Malcolm Gladwell's "Outliers": Research shows that 10,000 hours of work are needed to achieve mastery in a particular endeavor – and such mastery creates conditions for creativity.

Long hours are part of the Korean work ethic, starting from grade school on into careers. After a regular school day, students often do a second shift in private academies known as hagwans. Some students spend 12 or 13 hours a day in one school or another. Even parents who find it excessive say they feel compelled to help their children prevail in this competitive culture – and, it follows, anywhere else in the world.

South Korea's human wave also includes a global legion of multilingual corporate representatives, entrepreneurs, and students. Seoul Global High School is a public boarding school that aims "to nurture international specialists." It selects students through an application and interview process, and teaches in both Korean and English. Twenty percent of its graduates attend foreign universities, mostly in the US, with the rest typically entering South Korea's elite universities. Seoul Global's dorms discourage the hagwan system, but it's still intense: Tae kwon do is mandatory, with first-year students starting at 6 a.m., and music is mandatory as well. "They can graduate only if they know how to play an instrument," the principal explains.

The education obsession, blamed by some as a factor in the high suicide rate, has moved South Korean students toward the top in international academic rankings. Koreans, Choi says, "have a passion for being No. 1."

Electing a woman to face the North

With the inauguration of Ms. Park, South Korea claimed another first. "It's a great thing! Our people selected a lady president!" Ahn, the retired Army general, says. "How wonderful it is!" No other nation in Northeast Asia, he notes, has ever elected a woman as its leader. "When do you think a lady prime minister will be chosen to lead Japan? Or China? Or Russia?"

He has other reasons to be happy. In electing a conservative, Korea's voters, in a sense, affirmed Ahn's recent service as a top national security adviser to conservative Mr. Lee and the handling of the 2010 clashes with North Korea. The election of Park last December signifies continuity more than change.

The looming question is whether Park and Mr. Kim will navigate toward war or peace. Also key is how China, long supportive of Pyongyang and of a divided Korea, will apply pressure, given Beijing's displeasure over Kim's nukes.

In his unpretentious Seoul home, Ahn politely demurs from a discussion of politics, preferring to discuss Korean character. He shows his "family book," which he says records 28 generations. (Mr. Yoo, the cabbie, brags his goes back 31.) There is a box of Titleist golf balls on his desk, and beneath the glass desktop is a favorite proverb: "If there's no road, make it. Hope starts here."

The Sunshine Policy was such a road. The name was inspired by Aesop's fable about a contest between the wind and the sun to force a man to remove his cloak. The wind just made the man grip his cloak tighter, while the sun's warmth inspired him to remove it on his own.

The policy had produced tangible advances. But progress stalled and tensions resumed, culminating in the clashes of 2010. After the North's "Dear Leader," Kim Jong-il, died in late 2011, there was hope that his son, who had been educated in Europe, might chart a new course. But today a common perspective here is that after South Korea offered an olive branch, the young Kim brandished weapons of mass destruction.

A journey to the DMZ offers as little insight into the cloistered, enigmatic North as a shopping spree in Gangnam. Instead, it's better to hike up a hill through an old, gentrified neighborhood north of the Han River and visit the North Korea Graduate School of Kyungnam University. Inside the library, in a room marked "restricted access," a collection of recent North Korean publications includes the nation's largest news-paper, with a front page laid out as sheet music and lyrics extolling Kim and titled "The Person Who Holds the Key to Our Fate and Future." Inside pages display undated propaganda photos flaunting the nation's firepower and resolve.

These glimpses of North Korea's menace contrast with the urbane panorama of Seoul, which from this vantage includes the Blue House, the nation's executive office and home to Park. Like her counterpart in Pyongyang, she is heir to a political legacy, but otherwise the two have little in common. At 61, she is twice Kim's age. While Pyongyang has bizarrely faulted her "venomous swish of skirt," she is perceived as very much her father's daughter, with a toughness and pragmatism tempered by experience. "To most South Koreans, Madame Park is not so much a woman leader as [she is] her father, Park Chung-hee, personified in a woman's body," says Bong Young-shik, a senior research fellow at the Asan Institute.

South Korea's new president was a young student in France when, in 1974, her mother was killed in an assassination attempt on Mr. Park, prompting the young Ms. Park to assume the duties of first lady. Five years later, after her father was killed by his own spy chief during a drinking bout, it's said that her first concern was that North Korea might seize the moment to attack. She never married and later served in the National Assembly, immersing herself in politics. Her campaign played "the gender card," Mr. Bong says, but also emphasizes her experience in the Blue House, the mentorship of her father, and political experience. During the Sunshine period, she met Kim's father in Pyongyang.

On May 7, Park visited President Obama at the White House. At a joint press conference both affirmed the nations' solidarity and vowed that Pyongyang's threats would not win concessions. "North Korea will not be able to survive if it only clings to developing its nuclear weapons at the expense of its people's happiness," Park said. "However, should North Korea choose the path of becoming a responsible member of the community of nations, we are willing to provide assistance ... with the international community."

Can the North do the Gangnam gallop?

Back in Gangnam, Mr. Kim, the retired civil servant, gives a thumbs-up. That's his opinion of Psy, whose popularity is something to behold. Industrial warriors, college professors, students, random shoppers – all seem to root for Psy. Young people say that when they travel abroad – and are invariably asked if they're Japanese or Chinese – new acquaintances are excited by the answer.

"Some people start doing the dance," says a 20-year-old woman at a cos-metics shop, laughing as she demonstrates the Gangnam gallop. Her phone buzzes – and she answers first in English, then French, then Korean. Later she explains that she recently moved home after several years in Paris – and that, thanks to K-pop, Parisiennes now tell her they want to visit Seoul.

Many South Koreans profess indifference to Pyongyang, and many are quick to offer political assessments. The comments jibe with that April survey by the Asan Institute that showed, for the first time, more southerners considering northerners strangers or enemies rather than "one of us" or neighbors.

"There is a fundamental break happening in attitudes on the North," Karl Friedhoff, an Asan spokesman, wrote in an e-mail. "While previously South Koreans wanted to see the South absorb the North, there has been a change in that a majority, albeit slim, would prefer to see a federation – the two states co-existing."

But the future may hold a different scenario. The idea of reunification now seems daunting. There is the human dimension: Time, many point out, has faded old family ties. After generations of divergent experience, are Koreans really still one great tribe of 75 million people? Could South Koreans respect northerners as equals? And then there's the economic effect: How much would this cost? How much would taxes go up? In a merger of strength and weakness, could South Korea lift up the North – or would the North drag its neighbor down?

The feeling persists that reunification may be inevitable – even though the differences may be irreconcilable. A single Korea has always been a pretty thought. But getting there, and being there, could get ugly.